Hold on to your stars, ladies and gentlemen

Our galaxy is heavier and spinning much faster than scientists thought

|

|

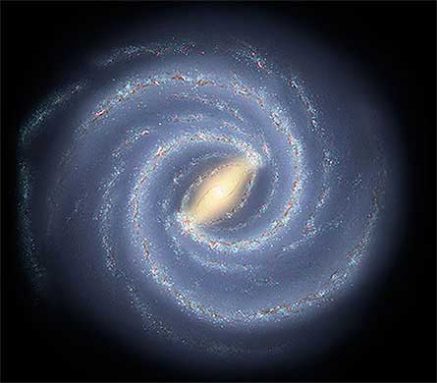

A new study of our galaxy, the Milky Way, says that it is heavier and faster than previously thought. Scientists also uncovered that our galaxy has four arms — two of which contain only newborn stars.

|

| Robert Hurt, IPAC; Mark Reid, CfA, NRAO/AUI/NSF |

We live on Earth, which orbits the sun. Our sun is really a star, one of the hundreds of billions in our galaxy, the Milky Way. Our galaxy has a few galactic neighbors, and together we’re called the Local Group. Until recently, scientists thought that our beloved galaxy was about half as massive as Andromeda. That’s a nearby galaxy in the Local Group. They also thought the Milky Way was spinning slower than its neighbors.

Just as it’s difficult to tell how large the ocean is when you’re in the middle of it, floating on a raft, scientists have been mistaken about the size of the Milky Way. Based on new data, astronomers — scientists who study the universe — have produced a new map of the Milky Way. It shows that our galaxy is about 50 percent more massive than scientists had thought. It is also spinning about 100,000 miles per hour faster. These two measurements are connected: The more mass a galaxy has, the faster it spins.

Far from being the littlest member of the Local Group, the Milky Way actually is one of the fastest-spinning and most massive. The new study suggests our galaxy has as much mass as roughly 3 trillion suns. That’s about as hefty as the Andromeda galaxy, putting the Milky Way now in a tie with it as the largest members of the Local Group. The new measurements also mean that these two galaxies will smash into each other earlier than astronomers thought. (But don’t worry — that’s not for a long, long time.)

The new study also turned up surprising findings about the shape of the Milky Way. Astronomers found that our galaxy has four arms. Two contain all kinds of stars (like the sun), and two contain only newborn stars. The researchers also were able to count how many times each arm wound around the galaxy’s center.

To study the Milky Way, Mark Reid of Harvard University and other astronomers used an unusual type of telescope. Instead of looking into the sky for visible light — like we see in the night sky — this radio telescope measures radio waves that move through space. (On Earth, we use radio waves to send information through the air. In space, however, cosmic objects also send out radio waves, though they tend to be spaced much closer together than the radio waves we use on Earth.)

When astronomers use light telescopes, they can’t see through thick layers of dust in space. But when they use radio telescopes, dust isn’t a problem. So astronomers can “hear” what’s going on in space. In the new study, astronomers listened to regions of the galaxy where the radio waves were amplified, or increased, by clouds of methanol gas. By measuring how fast the sources of these waves moved, scientists were able to calculate the speed of the galaxy. And from the speed, they were able to better estimate the Milky Way’s mass.

The new, more accurate map of our galaxy may lead to a better understanding of it. A more accurate mass will give scientists clues about how our galaxy has changed over time. But more research needs to be done before astronomers can be sure what, exactly, the Milky Way looks like.