Holiday fireworks can bring extreme pollution, India finds

A short-lived spike in pollution may make breathing more difficult for nearby residents

People take photos as a fireworks extravaganza reaches its climax.

sert/iStock/Getty Images Plus

By Matthew Cappucci and Janet Raloff

Holidays are generally supposed to be fun. But big celebrations can sometimes bring big risks. Massive fireworks displays delight the eye, for instance. They also can fill the air with pollution that hangs around for hours or more. It’s something that people in India had long suspected. Last year, data emerged showing that fireworks bring choking pollution to many people, here, during the festival of Diwali.

This annual four-day Hindu religious celebration commemorates the triumph of good over evil, knowledge over ignorance — and light over darkness.

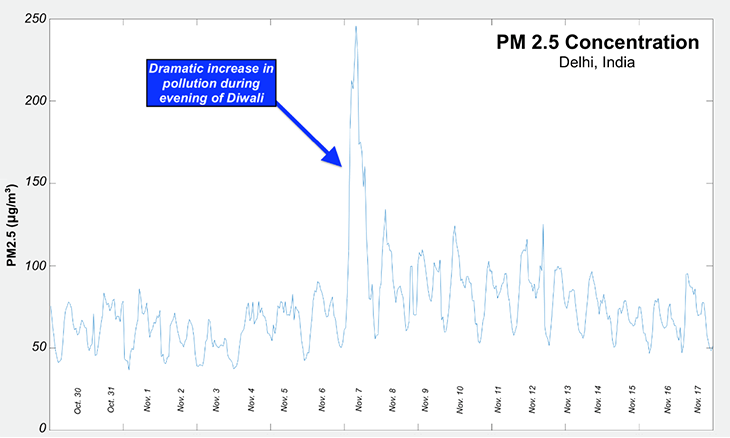

After the main day of revelry, people celebrate by setting off firecrackers. They can do it all night long. On the day after last year’s Diwali fireworks, people in New Delhi, India’s capital city, awoke on November 7 to especially dirty air. The levels had spiked overnight, starting around when the fireworks began. And in an urban area that is home to 29 million people, a lot were affected.

What’s more, data from the 2018 Diwali festival were no fluke.

A study that came out last August turned up a recent, consistent trend. It linked Diwali fireworks in the Indian capital to short term — but extreme —air pollution. Indeed, the authors of that study concluded: “To our knowledge this is the first causal estimate of the contribution of Diwali firecracker burning to air pollution.”

For 15 years, a growing body of research had raised concerns about such pollution.

Balram Ambade was one of those concerned scientists. He is a chemist at the National Institute of Technology in Jamshedpur, India. Last December, he presented data on particulate matter (or PM) from Diwali fireworks in his city. Scientists measure such pollution in micrograms per cubic meter (μg/m3) of air. In a 12-hour period on the holiday, PM values soared to 500.5 μg/m3. That rise was about 21 to 27 percent higher than before the fireworks went off.

A series of such studies had prompted India’s 31-member Supreme Court to pass a new ban on fireworks last year. Only “green” fireworks could be sold leading up to the holiday.

India’s Council of Scientific and Industrial Research has been working to create these more environmentally friendly fireworks. They emit less pollution. Still, they are not pollution-free. So even these approved fireworks could only be set off between 8 and 10 p.m., the court ruled.

Despite such a rule, India found it hard to enforce the ban. Many people still set off firecrackers. And air monitoring stations around New Delhi showed that PM levels spiked overnight from November 6 to 7. Amounts of the smallest and most risky particles, known as “fines,” topped out at nearly 250 μg/m3 — a whopping 150 μg/m3 above normal.

Focusing on ‘fine’ particles

Dhananjay Ghei at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis teamed up for a related but longer study with Renuka Sane at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy in New Delhi.

At the best of times, India’s capital tends to be one of the world’s most polluted, they note. Its air is dirtiest from October to January. It’s PM pollution is a mix of sooty and metallic bits and tiny liquid droplets. Each can be so small that it hangs in the air for hours, days — sometimes even for weeks.

The burning of fossil fuels — coal and oil — is a major source of PM. And the smaller that those particles are, the more deeply they can enter the lungs, causing harm. So the most harmful particles are those fines. Being 2.5 micrometers in diameter or smaller, they also are known as PM2.5.

Tailpipe emissions from cars and trucks are a major source of fine-size PM. That’s why in India’s capital, levels of these pollutants rise during the morning commute, then fall around lunchtime. They surge again in the evening as people drive home from work.

What Ghei and Sane wanted to know was whether fireworks intensified New Delhi’s fine pollution. To find out, they focused on PM2.5 data from four sites across the city.

Accounting for seasonal changes

One challenge: Diwali does not occur on the same date, each year. Based on a lunar calendar, it moves from year to year between October and November. Sometimes it occurs at the same time that farmers burn harvest wastes. Other times it does not. The researchers used hour-by-hour data from four straight years to see if they could tease out whether fireworks, crop burning or something else could explain the very dirty air seen during Diwali.

They looked over data from the week before Diwali through the days right after it. And they looked at precisely when and how PM levels changed during that period. They were hunting changes that coincided with the fireworks revelry.

And they found some.

Overall, “We find that Diwali leads to a small, but statistically significant increase in air pollution,” Ghei and Sane reported. How big that increase was varied across the four sites. It also varied some by the year (2013 to 2016).

The data showed that fireworks are partly to blame for making the air unhealthier than normal.

Of course, what Ghei and Sane call a “small” rise may be viewed differently by other air pollution experts. The Diwali effect they found was an increase of roughly 40 μg/m3. As they note, this is on top of “a base of already high pollution” at that time of year in the Indian capital — potentially hundreds of μg/m3. For perspective, U.S. law prohibits PM2.5 levels that are higher than 35 μg/m3 for longer than 24 hours. In fact, the U.S. limit falls to a mere 12 μg/m3 for periods longer than a day.

So these researchers observed an uptick in pollution that would have turned even super-clean air unhealthy. Diwali’s bonus pollution also was arriving at a time of year when the city’s air was not super clean.

Ghei and Sane described their data in the August 1, 2018 issue of PLOS ONE.

Plenty of other sites see fireworks pollution, too

Some places in China, the home of fireworks, also see sharp spikes in pollution after big celebrations. One 2017 study, for instance, found a 4- to 6-fold boost in air pollution within four hours of fireworks. And pollution levels didn’t fall back to normal for two to three days. Or so reports a team led by Yang Song of Shandong University in Jinan, China.

India’s capital city is not the only one to suffer a Diwali effect. Tirthankar Banerjee is an atmospheric physicist. He works at Banaras Hindu University in Varanasi where in 2014 he led a local study. Equipment on his university campus measured all sorts of air pollutants every four hours in the days leading up to and through the 2014 Diwali festival. Fine PM levels spiked after the fireworks. At the same time, the team saw a similar rise in certain metals used in fireworks. Those metals appeared to mark this pollution as coming from the fireworks, the team reported in 2016.

Last year, scientists used similar tracers to confirm a link between a spike in fine pollution in the air over South Korea and distant lunar New Year’s celebrations in China.

Pollution can become an important issue even for U.S. cities around the 4th of July. Dian Seidel led one research team that investigated this. At the time, she worked for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in College Park, Md. She and a colleague scoured hourly data on PM2.5 levels collected before and during the Independence Day celebrations between 1999 and 2013.

Pollution rose dramatically in the hours during and after the fireworks, they noted in a 2015 paper. In Ogden, Utah, for example, levels of PM2.5 peaked after one July 4th fireworks display at almost 500 μg/m3. Fortunately, it didn’t hang around.

Still, the monitoring site in Ogden, Utah was right next to the fireworks display. As such, the authors point out, the high pollution values seen there “may be more representative of exposure to spectators than results from other sites.”

Dan Satterfield is a meteorologist who blogs about pollution for the American Geophysical Union. He described one 4th of July event in Washington, D.C., a few years ago. “The smoke was so bad on the Mall that you could not see the end of the show!” he wrote. “The air quality sensors across the country always show a big bump on the evening for the 4th.” On this year, he pointed out, an early evening thunderstorm helped to trap fireworks pollution low to the ground.

How toxic is fireworks pollution?

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, PM pollution can harm your lungs and your heart. Studies have shown such pollution can cause early deaths in people with heart or lung disease, the agency’s website notes. PM also can trigger nonfatal heart attacks. It can make someone’s asthma worse. And it can irritate the lung’s airways, making it hard to breathe. People facing the biggest health risks from this pollution are children, the elderly and those with heart or lung disease, EPA warns.

But certain aspects of fireworks PM may pose special risks, Banerjee says. “Emissions from fireworks are very important as they potentially emit a huge amount of metals,” he says, “which are mostly carcinogenic.” In addition, he notes, for very short periods the mix of fireworks pollutants can build to “exceptionally high” levels. At this point, he told Science News for Students, “You know, it becomes tough to even breathe.” The problem: Young people enjoy going to fireworks festivals, he says, “without knowing the [risks].”