This hominid may have shared Earth with humans

Both our species and Homo naledi appeared to have lived at the same time

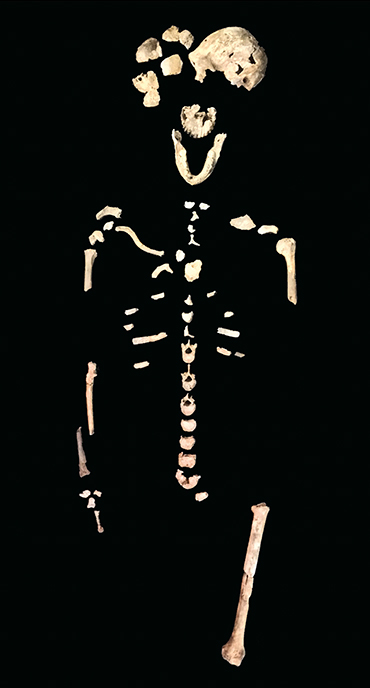

The skull of this adult male hominid was unearthed in an underground cave. Members of his Homo naledi species may have roamed what is now South Africa as recently as 236,000 years ago, claim the authors of a new study.

WITS UNIV., J. HAWKS

By Bruce Bower

A humanlike species with some fairly ancient skeletal traits appears to have lived in southern Africa close to 300,000 years ago, a new study concludes. If true, this species would have been around at about the time humans emerged. This raises the surprising possibility that both our species and this other hominid might have coexisted.

The newly studied fossils come from a species that has been dubbed Homo naledi. Two years ago, this species achieved worldwide acclaim as perhaps being a pivotal player in the evolution of our genus, Homo. That earlier cache of H. naledi bones had appeared to be quite old. Estimates had put them at between 900,000 and 1.8 million years old.

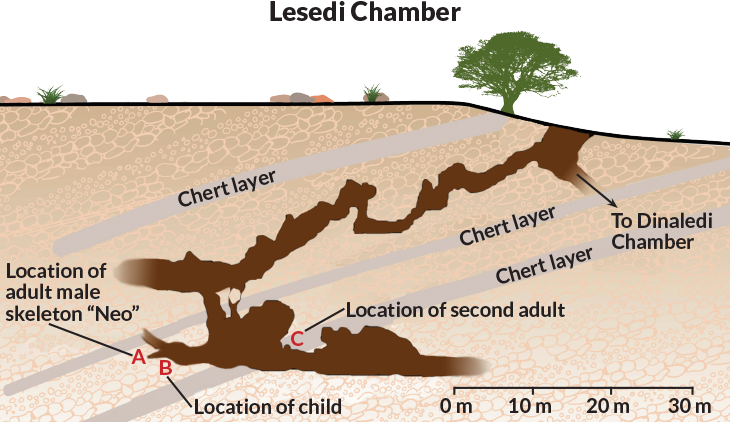

Both those old fossils and the newfound ones come from the same Rising Star cave network in South Africa. They were just found in different underground chambers. The newer bones somehow ended up in the network’s Dinaledi Chamber some 236,000 to 335,000 years ago. That’s the conclusion of an international research team. Lee Berger headed the group. He’s a paleoanthropologist in South Africa at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. Geoscientist Paul Dirks of James Cook University in Townsville, Australia, directed the team’s dating effort.

Their group shared its findings in a trio of papers published May 9 in eLife.

As interesting as their new, younger age for H. naledi is, it does not solve two important puzzles: When did this species first emerge and when did it die out?

What the new fossils show

Researchers used two methods to try and date the new fossils. For instance, they measured the levels of uranium and other radioactive elements in three H. naledi teeth. They also assessed damage to the teeth caused by those elements over time. In addition, the scientists used the radioactive elements to date a thin sheet of rock that had been deposited just above the fossils by water flowing through the cave.

A second new paper describes 131 newly discovered H. naledi fossils found in a second underground cave, dubbed Lesedi Chamber. It’s within the Rising Star cave network. This work, by Berger’s group, was led by John Hawks. He’s a paleoanthropologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

The bones come from at least three individuals. They include some from an adult male. Although all of his bones are not there, the share that’s present is comparable in completeness to those of Lucy. She’s a 3.2-million-year-old human ancestor found in East Africa. She belonged to the species Australopithecus afarensis (Aw-STAHL-oh-pith-ih-kus AF-ur-REN-sis). In each case, only about 40 percent of each skeleton has turned up.

Berger and Hawk’s team named the newfound partial skeleton of the male “Neo.” It means gift in Sesotho. That’s a language spoken in South Africa.

No signs indicate that predatory animals or streams carried H. naledi corpses into the caves. As such, Berger’s group says the Lesedi Chamber discoveries support their controversial suggestion that H. naledi deliberately placed bodies of its dead into the cave’s chambers.

Remains from both underground chambers display the same distinctive skeletal features. These include relatively small, orange-sized brains and curved fingers like those of a Homo species that lived around 2 million years ago. In addition, the skeletal remains have wrists, hands, legs, feet and body sizes comparable to those of Neandertals and humans. Taken together, the researchers argue, the newfound bones all belong to H. naledi, not some other Homo species.

When did H. naledi evolve?

Despite the relatively young age of the new fossils, their features have ancient-looking characteristics. Indeed, Berger and his colleagues propose in a third new paper, these traits suggest H. naledi originated near the root of the Homo genus. That likely would have been 2 million years ago or more. This would make the South African species a possible ancestor or close relative of H. erectus, which dates to around that time. The oldest Homo fossils date to 2.8 million years ago in East Africa.

But there’s also another possibility, Berger’s group says. Perhaps H. naledi evolved just a few hundred thousand years ago. Then it would be most closely related to early H. sapiens or other Homo species that may have inhabited southern Africa back then. A relatively late origin for H. naledi would suggest it evolved from larger-brained ancestors, the researchers say. That would be unusual: Scientists had argued for a long while that the hominid brain only became larger as Homo species evolved.

But that proposed scenario has some parallels to Indonesia’s Homo floresiensis, better known as “hobbits.” These short hominids, whose remains date to between about 100,000 and 60,000 years ago, had chimp-sized brains. And, like H. naledi, they had some skull features resembling early Homo species. Hobbits either evolved smaller brains or retained small brains after splitting from a much older Homo species in Africa.

It’s unclear how H. naledi might have survived in Africa alongside larger-brained Homo species, perhaps even early members of our own. Occasional interbreeding in southern Africa — similar to what occurred later in Eurasia among H. sapiens, Neandertals and Denisovans — might have benefited H. naledi, Berger’s team says.

DNA analysis could help clarify H. naledi’s evolutionary status. So far, researchers have yet to test the newfound fossils for DNA or to try to generate firm age estimates for them.

“My intuition is that Homo naledi points to a diversity of African Homo species that once lived south of the equator,” Hawks says. It’s unlikely Homo evolution in Africa proceeded in a straight line here, from one species to the next, he adds.

What other scientists think

Some paleoanthropologists who have just learned of the new reports interpret the new findings differently.

An “astonishingly young” age for a Homo species with several ancient-looking features suggests H. naledi was the sole survivor of a group of much older, closely related species, argues Chris Stringer. He works in England at the Natural History Museum in London. H. naledi probably made some of the many stone tools found at southern African sites, he adds. A number of these sites hosted no hominid bones but date to around 300,000 years ago.

Despite Berger’s claims, Stringer doubts this species disposed of its dead deep within a pitch-black, hard-to-navigate cave system. Keep in mind, he notes, this creature had a brain size close to that of a gorilla. Moreover, the controlled use of fire for torches would likely also have been needed.

Berger’s team plans to excavate near openings to the Rising Star cave system. The researchers will be looking for any signs of stone tools and use of fire.

However complex H. naledi’s behavior may have been, ancient aspects of its anatomy rule it out as a direct ancestor of H. sapiens, says Donald Johanson. A codiscoverer of Lucy, Johanson now works at Arizona State University in Tempe. Our species originated in East Africa, he notes. Researchers generally place that evolutionary turning point at between 200,000 and 300,000 years ago. Says Johanson: “The Rising Star Cave hominids, much like the hobbits, evolved in isolation and have no relevance to the origins of humankind.”

Yet even a largely isolated H. naledi population might have interbred now and again with other Homo species in southern Africa, says Fred Smith. He works at Illinois State University in Normal. The relatively recent Homo evolution “is far more complex than has generally been thought,” he says.

On that, Berger and his colleagues agree.