How boa constrictors squeeze their prey without strangling themselves

The latest Wild Things cartoon from Science News Explores

A new comic series from Science News Explores

JoAnna Wendel

By Maria Temming and JoAnna Wendel

The boa constrictor’s choke hold is an iconic animal attack. Once coiled around its prey, in mere minutes a snake can squeeze the life out of a victim. The boa then gulps down its dinner whole. Now, X-ray videos show just how these snakes squeeze so hard — or swallow something as big as a monkey — without suffocating.

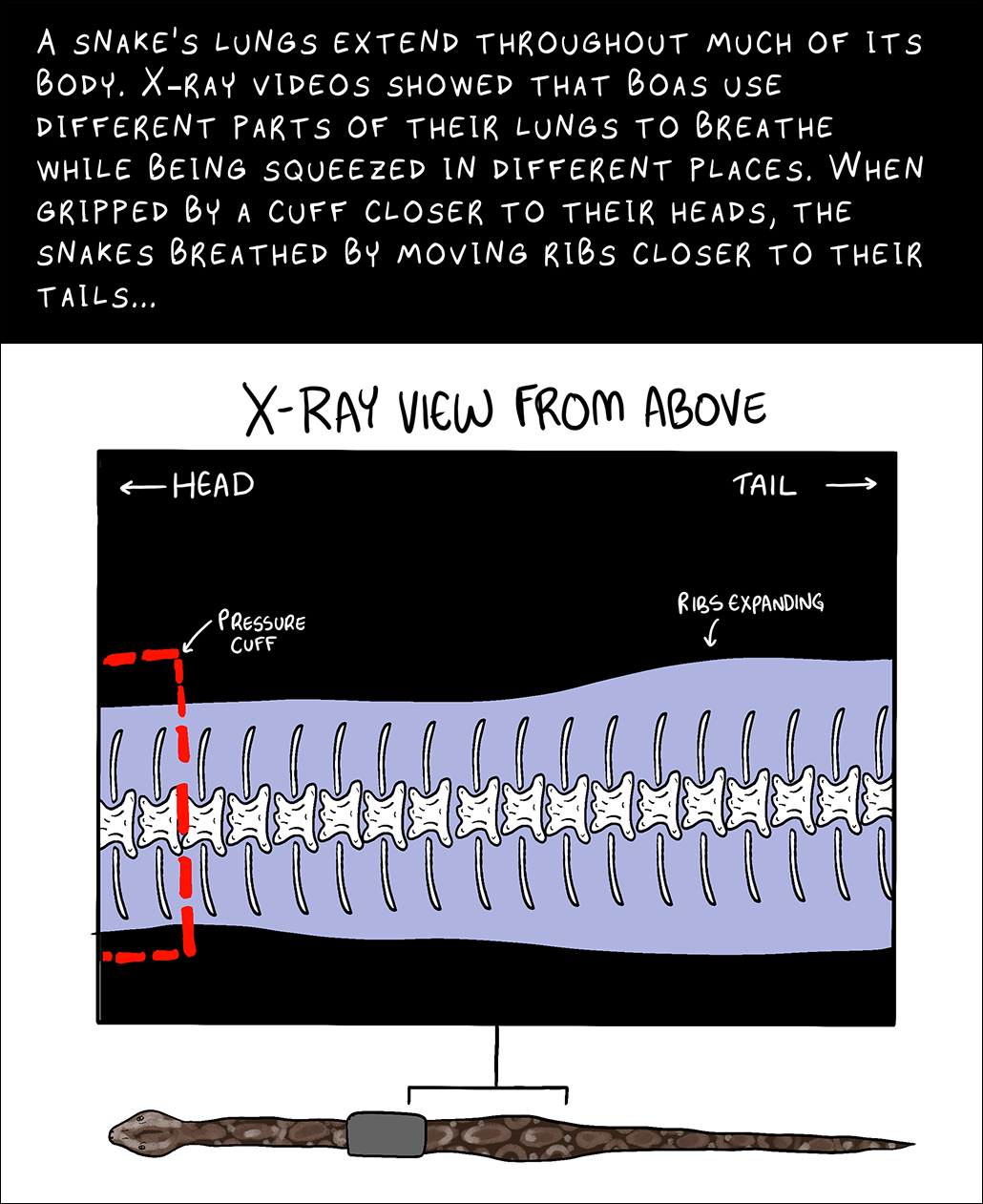

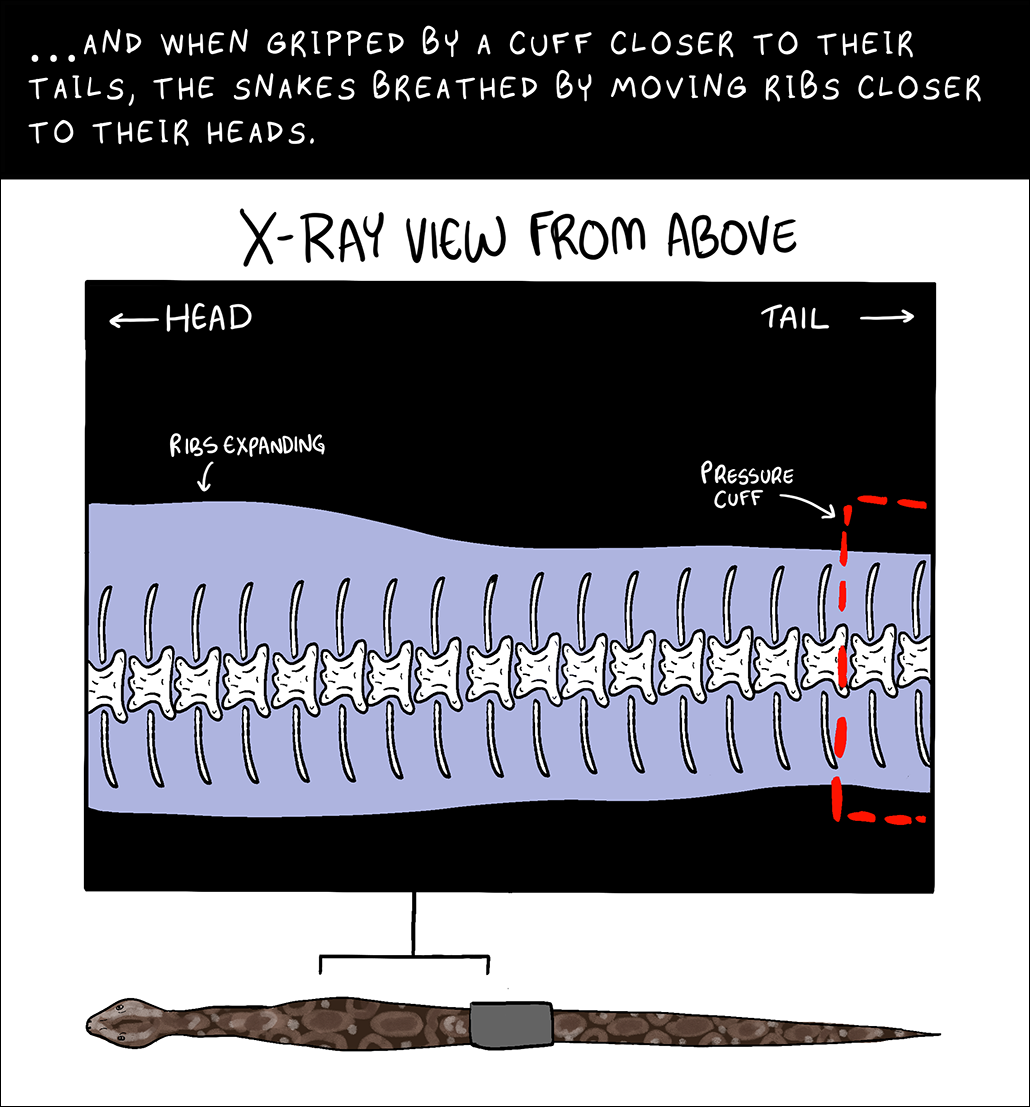

When one part of a Boa constrictor’s rib cage is compressed, the part of its lungs enclosed here cannot draw air. But the new videos reveal that a snake can simply move another section of its ribs to inflate its lungs there. That allows a boa to keep breathing even while one part of its body is squeezing.

Researchers shared their finding March 24 in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

Some people had reported seeing this behavior in snakes before. “But no one’s ever empirically tested that,” says John Capano. He’s a biologist at Brown University. That’s in Providence, R.I.

Capano and his colleagues wanted to take a closer look at how boas breathe. So, they implanted metal markers on the ribs of three boa constrictors. One set of markers was placed about a third of the way down the animals’ bodies. The other set was placed about halfway down the snakes. Those metal markers showed up in X-ray videos of the animals. This allowed the researchers to map rib motions over different parts of the snakes’ lungs.

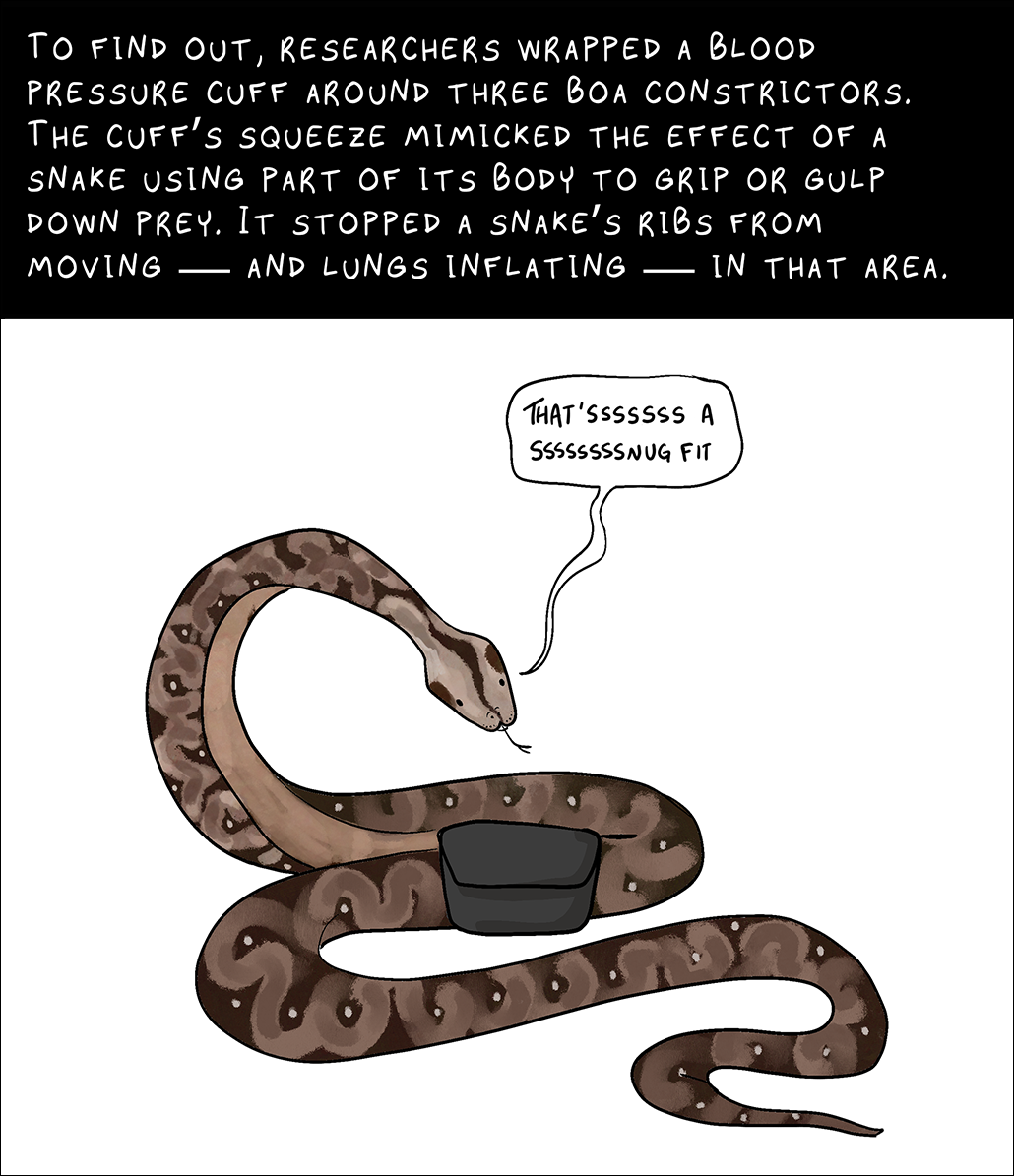

The team wrapped a blood-pressure cuff around different parts of the boas’ bodies. The cuff’s pressure slowly increased until a snake’s rib cage could not move in that area. This mimicked the effect of a snake using that part of its body to grip prey or gulp it down.

Some snakes reacted to the cuff better than others. “One was really, really calm. Never had to worry about her,” Capano says. “The other two, I had to watch my back quite a bit more. But they were all pretty amenable to it, once the cuff was on.”

Snakes at rest breathed by moving ribs near the front of their lungs. When gripped by a cuff about one-third of the way down its body, a snake breathed by moving ribs closer to its tail. When gripped by a cuff about halfway down their length, the snakes breathed by moving ribs closer to their heads.

“They can basically just breathe wherever they want,” Capano says. This ability was probably crucial for early snakes to start throttling and swallowing large prey, he adds. That’s important. Why? Snakes’ ability to eat big prey is thought to be a key reason these animals have adapted to so many habitats. Snakes are some 3,700 species strong. And they’re found on six continents.

Controlled breathing may be “one of the key innovations within snake evolution that allowed this group of animals to explode and become one of the most successful groups of vertebrates we’ve ever had,” Capano says.