How ‘brain-eating’ amoebas kill

For people infected with N. fowleri, the immune system may prove the primary cause of death

A sign at one of the more than 300 hot springs feeding into Nevada’s Lake Mead warns that this water is known to host Naegleria fowleri amoebas. The potentially deadly parasites can travel from someone’s nose into their brain.

© brianwbailey222/ Flickr (used with permission)

On July 9, just a few days after swimming in Minnesota’s Lake Minnewaska, 14-year-old Hunter Boutain was dead. Doctors think his killer was a single-celled parasite that lives in the water. Most people know it simply as the “brain-eating amoeba.”

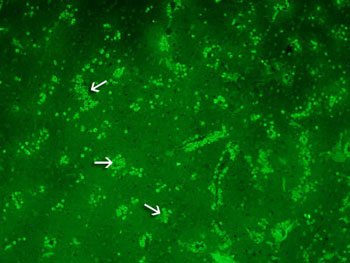

This microbe ultimately kills 97 percent of the people it infects. But its name may misguide people as to why this microbe’s infections are so deadly. New data indicate the real killer is not just the amoeba itself — Naegleria fowleri (Neg-LAIR-ee-ah FOW-ler-eye) — but also our immune system’s response to it.

In actions that sound like something from a horror movie, these tiny amoebas can slosh up a victim’s nose. From there they climb into the brain. That’s where the real damage occurs. But new data suggest the amoeba needs a new name, Baig says. Brain-eating amoeba, he contends, is “more a tabloid term.”

He and others suspect that death from the amoeba is actually more of an “inside job.” It may trace mostly to the victim’s immune response as it tries to fight the amoebas. Baig explains this theory in the August Acta Tropica. It’s based on new data. He’s found in the lab that when immune cells were missing from tissue infected with N. fowleri, the amoebas took eight hours longer to damage cells in human blood vessels.

Where the danger lies

N. fowleri often makes news for killing healthy people — often boys — by sparking a brain infection. The name of this disease is a mouthful: primary amebic meningoencephalitis (Ah-MEE-bic Meh-NIN-joh-en-SEF-uh-LY-tis). But cases of this disease remain rare. Between 1962 and 2014, only 133 people in the United States were known to become infected. That’s according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC, in Atlanta.

Most cases were in southern states. But since the infections can be hard to diagnose, their real total may be higher. And health officials have noted that the amoeba seems to be creeping northward.

Headache, fever and nausea are the first symptoms of an infection. There may even be an altered sense of smell. However, because of its rarity, this disease is difficult to study and fully understand. Still, experiments on cells in the lab have been offering clues.

It appears the amoeba damages tissue directly by releasing harmful proteins, explains Jesús Serrano-Luna. He’s a cell biologist at the National Polytechnic Institute in Mexico City.

Baig thinks doctors could help more patients survive by dialing down the body’s immune response — and the brain swelling that goes with it. In fact, reducing brain swelling may partly explain why 12-year-old Kali Hardig survived the amoebas in 2013.

“It was amazing at the time,” says Jennifer Cope of the CDC. As an epidemiologist, Cope helps investigate factors behind certain diseases or outbreaks. She consulted on Hardig’s treatment. And when it comes to N. fowleri , this girl “was the first U.S. survivor in 35 years,” Cope notes.

Several aspects of treatment probably saved Kali’s life. She got a quick diagnosis. Doctors also treated her with a new anti-amoeba drug, Cope notes. And the girl’s doctors worked hard to lower the pressure inside her skull. “Our skull is great. It protects us most of the time,” Cope says. “But when it comes to the inflammation in the brain and swelling, that’s when our hard skull works against us.” Like a wall, it provides an immovable surface against which the brain’s soft, swelling tissue can become damaged.

When N. fowleri attacks the brain, it starts a domino effect. The initial inflammation triggers dangerous swelling. Unrelieved, this can lead to death, Cope says. There’s some truth to calling the amoeba “brain-eating,” she says. However, she adds, as the new data show, “it’s also not the whole story.”

Power Words

(for more about Power Words, click here)

amoeba A single-celled microbe that catches food and moves about by extending fingerlike projections of a colorless material called protoplasm. Amoebas are either free-living in damp environments or they are parasites.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC An agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC is charged with protecting public health and safety by working to control and prevent disease, injury and disabilities. It does this by investigating disease outbreaks, tracking exposures by Americans to infections and toxic chemicals, and regularly surveying diet and other habits among a representative cross-section of all Americans.

epidemiologist Like health detectives, these researchers figure out what causes a particular illness and how to limit its spread.

immune system The collection of cells and their responses that help the body fight off infections and deal with foreign substances that may provoke allergies.

infection A disease that can spread from one organism to another.

inflammation The body’s response to cellular injury and obesity; it often involves swelling, redness, heat and pain. It is also an underlying feature responsible for the development and aggravation of many diseases, especially heart disease and diabetes.

Naegleria fowleri A single-celled freshwater parasite, sometimes called the “brain-eating amoeba.” It lives in hot springs and other surface waters that get very warm.

parasite An organism that gets benefits from another species, called a host, but doesn’t provide it any benefits. Classic examples of parasites include ticks, fleas and tapeworms.

physiology The branch of biology that deals with the everyday functions of living organisms and how their parts function. Scientists who work in this field are known as physiologists.

proteins Compounds made from one or more long chains of amino acids. Proteins are an essential part of all living organisms. They form the basis of living cells, muscle and tissues; they also do the work inside of cells. The hemoglobin in blood and the antibodies that attempt to fight infections are among the better-known, stand-alone proteins.Medicines frequently work by latching onto proteins.

tabloid The term for a newspaper printed on paper about half the size of a normal newspaper. This makes it convenient for commuters who read while riding on buses or trains. But over time, the term tabloid has taken on a more negative meaning. These smaller newspapers often have appealed to readers by publishing more lurid stories — those focusing on tales of crime, violence and scandal.

tissue Any of the distinct types of material, comprised of cells, which make up animals, plants or fungi. Cells within a tissue work as a unit to perform a particular function in living organisms. Different organs of the human body, for instance, often are made from many different types of tissues. And brain tissue will be very different from bone or heart tissue.