How bugs in your gut might hijack your emotions

Tiny molecules in the brain may help gut bacteria control anxiety levels, research suggests

Researchers have uncovered new clues about how bacteria in the gut influence anxiety levels. The findings could lead to new treatments for some mental-health disorders.

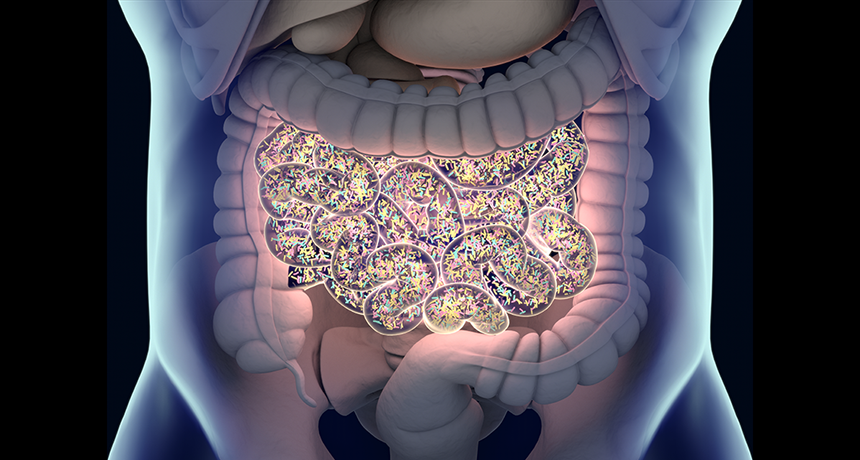

ChrisChrisW/istockphoto

Bacteria in the gut can influence someone’s mood. But scientists haven’t known precisely how those microbes do it. Now research in mice suggests that gut germs may alter the supply of certain molecules to regions of the brain involved in controlling anxiety.

The molecules are called microRNAs. They help keep cells in working order by managing the production of proteins that the cells need to flourish.

Many studies have also suggested that how we think and feel might “be controlled by our gut microbiota,” says Gerard Clarke. This psychiatrist in Ireland at University College Cork is a co-author of the new study.

Gut bacteria can affect whether a mouse shows anxiety-like behaviors, for instance. In people, anxiety might lead to behaviors such as avoiding certain social situations. In mice, a similar state might lead them to avoid bright lights or open spaces. His team’s new findings could help scientists develop new treatments for some mental health problems. Researchers shared their discovery online August 25 in Microbiome.

How they teased out the findings

In people and other animals, the gastrointestinal tract — or GI tract — is crawling with germs. The community of microbes living here is known as the gut microbiota (MY-kroh-by-OH-tuh). The idea of germs camping out inside you might sound gross. But most gut bugs are harmless. Some are even helpful. They might help our bodies use the nutrients in food. Others can help fight off infections or crowd the gut lining so disease-causing germs have a hard time moving in.

Clarke and his team studied two groups of mice. One group included normal mice, whose guts were teeming with bacteria. The other mice were bred in sterile (microbe-free) conditions. Their guts contained no germs. The researchers looked at two brain regions in both groups of mice. These areas are involved in controlling anxiety.

One area is the amygdala (Ah-MIG-duh-lah). The other is the prefrontal cortex. Compared to the brains of normal mice, those with microbe-free guts had more of some types of microRNAs and fewer of others. Later, after the germ-free mice were exposed to microbes, their microRNA levels more closely matched those of normal mice.

The team also examined the same two brain regions in rats whose gut bacteria had been destroyed by antibiotics. These are drugs designed to kill harmful bacteria. These rats either overproduced or underproduced some of the same microRNAs that were off-kilter in bacteria-free mice.

Clarke’s group now suspects that gut bacteria affect their host’s anxiety levels by tampering with microRNAs in specific parts of its brain.

What others make of the new data

“I was a little surprised by the findings — in a positive way,” says Peter Holzer. He suspects “not many people so far have thought about microRNAs in this context.” Holzer, who works in Austria at the Medical University of Graz, was not involved in the study. He does, however, conduct research on how the gut and brain interact. The new findings, he says, head scientists “into a new area in gut-brain research that hasn’t been pursued.”

Researchers still aren’t sure how these bacteria in the brain dial microRNA production up or down. Maybe the microbes send signals along the vagus nerve. That’s a kind of information highway that between the gut and brain. Or perhaps bacteria churn out molecular by-products that start some sort of chemical chain reaction. This might provoke the immune system to produce chemicals that provoke the brain to produce more or less of certain microRNAs.

Alas, Clarke says, figuring out how microbes manipulate the mind from start to finish “is still a work in progress.”

Next, his team wants to see if consuming probiotics and prebiotics might help restore production of microRNAs to normal levels in animals where it currently appears upset. Probiotics are beneficial germs that have been shown to foster gut health. Prebiotics are nutrients that those good germs need to thrive. Clarke and his colleagues would like to see if using these dietary supplements might help ease anxiety. If so, that could lead to new mental-health drugs.

Right now, such drugs may be unrealistic, says Kirsten Tillisch. She’s a gastroenterologist at the University of California, Los Angeles. She was not involved in the new work. “It is just so tempting” to assume that results in mice will hold true in people, she notes. But history shows that “the translation from lab animal to human is hit-and-miss,” she adds. So it may be too early, she cautions, to expect seeing these findings translate into therapies for people.