How do elephants eat cereal? With a pinch

Learning how elephant trunks pick up snacks could help engineers design flexible robots

With their long, flexible noses, elephants can eat whole tree branches like they were stems of broccoli. But they use a newfound tactic to pick up tiny bits of food, scientists have just shown.

johan63/iStockPhoto

Never challenge an elephant to an eating contest. A fully-grown elephant can down 200 kilograms (that’s 440 pounds) of greenery every day. It can snap off whole tree branches and munch on them like giant stalks of broccoli. But how do elephants keep up their eating pace when faced with smaller food pieces , such as a bowl of cereal? They simply press and pinch with their flexible trunks, a study now finds. This newfound tactic could guide engineers in designing better flexible robots.

David Hu usually focuses on the other end of an elephant. He is a mechanical engineer — someone who studies how things move. He works at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta. Hu and his colleagues had spent a lot of time at the Atlanta zoo taking videos of elephants from behind. Specifically, he notes, they studied “elephant peeing and pooping.” His lab had been comparing how quickly different animals get rid of their wastes.

But the other end of the elephant is interesting, too, pointed out a curator at the zoo. When Hu finally got a demonstration, he was impressed. “I’d never seen them eat anything,” he says. “When there’s lots to gather they’re very fast — I would almost say greedy.”

Hu’s team began to wonder how elephants used their trunks to gather different types of food. They were especially interested in how these animals picked up granular materials — things such as cereal, flour or sugar. “Granular material is anything made up of lots of smaller pieces,” explains Scott Franklin. He’s a physicist at the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York.

“Granular materials are between solids and liquids,” notes Karen Daniels. She’s a physicist at North Carolina State University in Raleigh and did not take part in the new study. Such materials behave unpredictably, she says. For example, when someone tries to pour cereal out of a box, it may get stuck. Bang on the box and a cereal avalanche suddenly overflows the bowl. Studying how other animals — such as elephants — lift weird materials might help engineers develop robots that can do the same thing.

Press and pinch

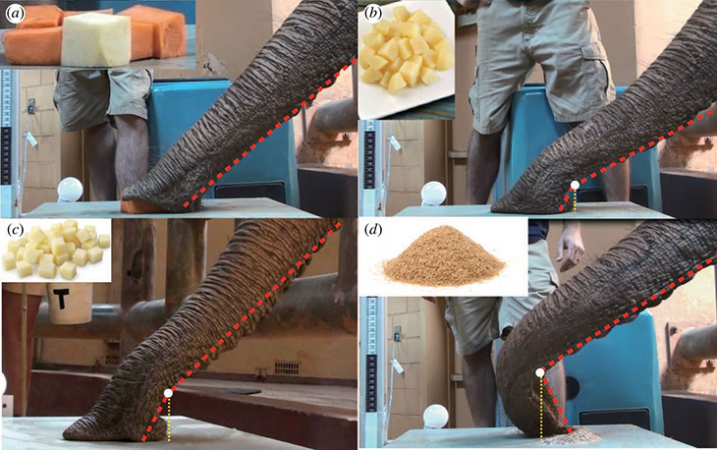

Hu, Franklin and their colleagues took video of Kelly, an African elephant at the Atlanta zoo. They filmed her eating rutabagas that had been chopped into large, medium and small cubes. They also tested Kelly on tiny grains of toasted bran cereal. You might think of these as the elephant equivalent of Wheaties. “Cheerios would be too expensive,” Hu explains. “She eats a lot. A box of Cheerios would only take about two minutes.”

Researchers placed Kelly’s snacks on a device called a force plate. It measures how much force the elephant used to grab the food atop that plate. Kelly got 24 sets of snacks. She reached out and curled her trunk around some rutabaga pieces. Then she scooped them from the side. This is a bit like grabbing a pile of things in the crook of your elbow, Hu explains.

The scoop didn’t require much force — only about six newtons. That’s about 10 times the force needed to press a computer key. Kelly used the same trunk-curling motion to pick up bigger veggie chunks. But she took a different tack with the small bits. Now Kelly stretched her trunk out and pressed down on the pile of food. Then she pinched the ends of her nose together to pick it up. As she pinched, the trunk’s tip formed a joint — an impressive feat for this long, boneless nose.

This push-and-pinch method took more work. When the cubes were large, it took about 10 newtons of force. For the cereal, it took about 40 newtons. That’s delicate work for a big trunk — using only about one-twentieth as much force, on average, as it takes for a human to bite something.

“When you pick up piles of particles, you’re using friction,” explains Franklin. That’s the resistance between objects rubbing against each other. With enough friction, particles stop moving. Instead of pouring like a cereal or sliding around like a pile of rutabaga chunks, the particles start acting more like one solid piece.

The more particles the elephant lifted, the more force she had to use. With only a few rutabaga chunks, there are fewer spots for friction. So Kelly didn’t need to press as hard. But with cereal, there are many friction spots — places for a grain to slip free. So the elephant applied a lot more pressure. Hu, Franklin and their colleagues published their findings October 24 in Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

A nose for inspiration

“I’m always jealous when I read [Hu’s] papers,” says Daniels at NC State. “He got to go to a zoo and do experiments with animals,” she explains. “I only do experiments in the lab.”

Elephants might be fun, but they also can be hard to work with. For instance, an elephant might decide, one day, not to cooperate. Still, Daniels thinks working with them is worth the effort. “It’s a way for us to get creatively inspired.” People trying to pick up a pile of cereal might think of a broom and a dustpan. An elephant doesn’t have that option. When you bring such a challenge to another animal, as here, “It gives you more and different ideas,” she points out.

The new findings aren’t limited to elephants anxious to scarf up snacks. The limbs on robots also might jam particles together to pick them up, says Daniel Goldman. He studies biophysics — the physical forces exerted by living things — at Georgia Tech in Atlanta. He was not involved in the study. “Soft robotic devices would be a natural for such things,” he says. Engineers could create flexible robots that can pick up small particles by jamming them together elephant-style. That might help robots take on all of life’s challenges — including picking up crumb-like bits.