How a flamingo balances on one leg

These extreme bird balancers stay upright with little muscle effort

Scientists have tackled the question of how flamingos manage to balance — and apparently even nap — on just one skinny leg.

CLINT/ISTOCKPHOTO

By Susan Milius

Why do flamingos stand on one leg? Flamingo researchers get asked this question all the time. But why flamingos ever bother standing on two may be the bigger puzzle, new research suggests.

Flamingos have balance aids built into their bodies, the new study finds. That lets them stand on one leg with little muscle effort. The stance is so stable that a bird sways less (to stay upright) when it appears to be dozing than when it’s awake.

“Most of us aren’t aware that we’re moving around all the time,” says Lena Ting of Emory University in Atlanta, Ga. Just to keep our bodies standing up, we have to sense our position constantly and use our muscles to correct wobbles. Ting studies this movement, called postural sway, in people and other creatures.

Even standing robots “are expending quite a bit of energy,” Ting says. Flamingos look relaxed when they stand. But they might be working hard to stay upright too, she points out, since limiting sway isn’t always easy to see.

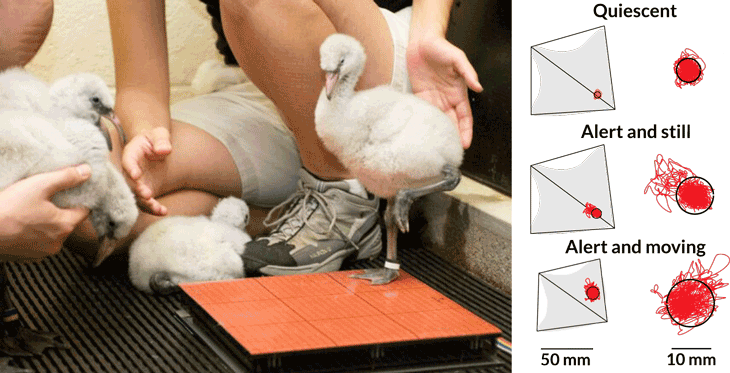

Ting and Young-Hui Chang of the Georgia Institute of Technology (also in Atlanta) tested balance in Chilean flamingos. These animals reside at Zoo Atlanta. Zookeepers there coaxed fluffy young birds onto a platform. It was attached to an instrument that measured how much the birds swayed. The researchers especially wanted to study birds sleeping on one leg. So the zoo let the scientists visit after feeding time. That way they might catch young birds ready to nap. “Patience,” Ting says, was key to her team’s success.

Story continues below image.

As a bird stood on one foot, the instrument tracked changes in the foot’s center of pressure — the spot over which the bird’s weight was focused. This spot wobbled around as a bird shifted to preen its feathers or look at a neighbor. But once a bird tucked its head onto its pillowy back and shut its eyes, the center of pressure made smaller changes. When birds were dozing, their center of pressure moved within a radius of 3.2 millimeters (0.1 inch), on average. That center of pressure expanded to 5.1 millimeters when the birds were active.

The researchers also studied flamingo skeletons in a museum. They saw features of the skeleton that might make birds more stable. Still, bones didn’t tell the whole story.

Researchers learned more from the whole bodies of a few dead Caribbean flamingos that a zoo had donated to them. “The ‘ah-ha!’ moment was when I said, ‘Wait, let’s look at it in a vertical position,’” Ting remembers. All of a sudden, the bird specimen settled naturally into a one-legged lollipop stance. There was no way a dead bird could be putting muscle effort into keeping that position. So the body must have some built-in ways to hold this stance without effort.

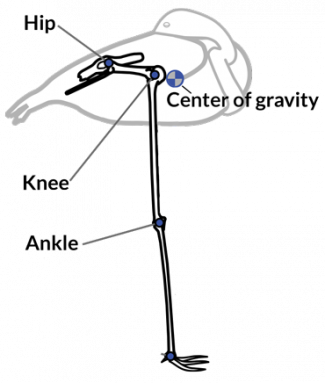

A flamingo’s hip and knee sit high up inside its body. What bends in the middle of the long flamingo leg is not a knee, but an ankle. (That explains why, to human eyes, a flamingo’s leg looks like it bends the wrong way.) Ting didn’t find anything that locks the leg bones upright. She did, however, see other features of the skeleton that might help flamingos stand steadily.

How the bird distributed its weight also seemed important for one-footed balance. The flamingo’s center of gravity was close to the inner knee. That’s where the bone starts to form the long column to the ground. This made the shaky-looking one-leg nap actually stable. In fact, tests with dead birds showed the body was floppier and less stable when researchers fastened it upright on two legs instead of one. The researchers reported their findings May 24 in Biology Letters.

Reinhold Necker is cautious about saying the one-legged stance saves energy until researchers discover more. “The authors do not consider the retracted leg,” says Necker. At Ruhr University in Bochum, Germany, he has written about one-legged standing in birds. He says keeping one flamingo leg tucked up might take some energy, even if easy balancing saves some. (Ting thinks flamingos might have some special energy-saving way of holding up that other leg. The question needs more research.)

The new study helps researchers understand how flamingos stand on one leg. Still, it doesn’t explain why they do it, says Matthew Anderson. He’s a comparative psychologist at St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia, Penn. He’s found that more flamingos rest on one leg when temperatures drop. So he thinks that keeping warm might have something to do with it.

The mystery of flamingos, in other words, still stands.