How not to grin and bear it

Teen researchers develop ways to identify teeth clenching and grinding

People may clench their teeth when dealing with a stressful situation, as here. But when the problem occurs frequently, and unknowingly, it can develop into a health problem, known as bruxism.

piksel/iStockphoto

By Sid Perkins

Ever find yourself clenching your jaw or grinding your teeth? Maybe it happens while taking a difficult test in school. Or standing at home plate, baseball bat in hand, waiting on a fastball. Clenching teeth in a stressful situation is common, scientists say.

But there’s a related medical condition that’s much more severe. Called bruxism, this term gets its name from the Greek word brychein, which means “to gnash the teeth.” Over the long term, bruxism sufferers gnash their teeth so much that it can cause them to wear down. It also can cause sore jaw muscles and headaches. In severe cases, people can clench hard enough to crack a tooth.

There is no easy way to get someone with bruxism to stop. Researchers are, however, working on treatments. But first, people need to know they have a problem. And three young teens have begun to tackle that challenge.

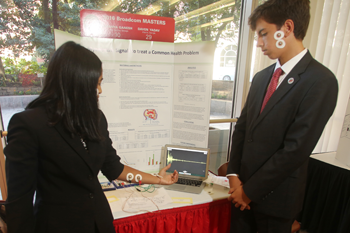

All were finalists in this year’s Broadcom MASTERS competition. This event brings 30 middle-school researchers together each year to tackle team challenges. But about a quarter of each finalist’s score will be based on the project he or she entered in a science fair the previous school year. The projects by three of the 2016 finalists had probed ways to identify when people are clenching and grinding their teeth.

Each of these students had a personal connection to bruxism. For instance, Ananya Ganesh, 14, of Sandy Springs, Ga., suffers from the condition. “I’m a habitual jaw clencher,” she says. Her research partner, Daven Yadav, 14, of Atlanta, Ga., has a sister with bruxism. And Aalok Patwa, 13, of San Jose, Calif., decided to study teeth grinding and clenching after his father woke up one morning with a cracked tooth. That was the first sign, the teen notes, that his dad suffered from bruxism. All three teens now hope that work such as theirs may one day lead to remedies.

For her work on bruxism, and her performance in other team challenges, Ananya landed a first-place award in science, worth $3,500. (The overall, first place winner for this year’s Broadcom MASTERS went home with an even bigger, $25,000 educational award.)

MASTERS stands for Math, Applied Science, Technology and Engineering for Rising Stars. Broadcom Foundation sponsors this competition, which was created by — and is run by — Society for Science & the Public. (SSP also publishes Science News for Students.)

A common predicament

Recent studies suggest there are two forms of bruxism, notes Gary Klasser. He’s a dentist at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans. “Sleep bruxism” is where people grind their teeth as they snooze. This is what Aalok’s dad might have. And he’s not alone. Surveys suggest that about 8 percent of adults (or one out of every dozen) has this condition. It’s even more common in kids. Somewhere between 14 and 46 percent of children and adolescents report grinding their teeth at night, Klasser notes.

The other form is known as “awake bruxism.” It’s what Ananya suffers from. Between 5 and 12 percent of other children do too, says Klasser. But adults are more likely to suffer this form. An estimated 20 to 25 percent report clenching their teeth while awake.

No matter which form it takes, bruxism typically occurs without someone being aware of it. That makes this condition an unconscious behavior, says Klasser. To fix such a problem, the patient usually has to be alerted as it is occurring, not afterward.

That’s the approach Anaya, Daven and Aalok have focused on. They have been working to develop a way to identify that clenching or grinding behavior. If successful, they might be able to tip off the person when it’s happening. And that could become the first step in learning to stop. This process — becoming aware of an unconscious behavior and then learning to control or eliminate it — is called biofeedback.

Measuring muscles

Muscles contract when certain nerves inside fire off electrical impulses. Those signals often can be easily measured. Ananya and Daven wanted see if they could measure the muscle activity associated with bruxism. To do this, they used the same sort of sensors that doctors use when they’re testing patients for heart conditions. These sensors look like small, round adhesive bandages. The sensors have a small metal nub to which wires are attached. Those wires, in turn, carry electrical signals to a device that can record them.

The teens’ first target was the masseter muscle. This is one that connects the skull to the jaw. It runs just in front of the ear. It’s also a major muscle that contracts when people grind their teeth. One small problem, though: This muscle contracts when people chew food. And talk. That means its contraction alone can’t diagnose when someone is grinding their teeth.

So Ananya and Daven ran some tests. These measured electrical signals in the muscle generated by teeth grinding and while talking or chewing. Then they compared those signals. Those generated by bruxism are much stronger, they showed. That means it should be possible for a small, wearable computer to detect clenching or grinding, the teens say — and then alert someone to their bruxism.

Aalok had much the same idea. He, too, focused on measuring the masseter muscle’s electrical activity. (Great minds think alike!) But when he tried to measure the muscle’s contraction, he couldn’t get the technique to work.

So he tried another approach.

He attached an accelerometer to a volunteer’s chin. It’s a special sensor that detects changes in motion. (Many smartphones contain accelerometers to monitor their motions.) Aalok’s sensor measured the back-and-forth movements that the jawbone produces when someone grinds their teeth. Like Anaya and Daven, Aalok found that he could tell the difference between the signals generated by normal jaw motions and those due to bruxism.

What’s next?

There aren’t many proven treatments for either type of bruxism, notes Klasser. However, biofeedback is a promising approach, he says. Many devices, either in development or just being offered for sale, monitor electrical signals of the sort the students detected. Some of these devices monitor and record the number of times someone clenches his teeth. They also record how long the clenching lasts and the force being exerted by the jaw’s muscles.

Once such signals are detected, a patient can be warned. If the clencher is awake, a light or a sound might bring it alert them. Or, the system might vibrate a small patch on the skin. Some researchers have even suggested sending a tiny electrical jolt to the skin near the jaw muscle. Still others have proposed creating a device that releases a sour-tasting liquid into the mouth when clenching gets underway.

A few of these techniques might seem a bit, er, shocking. But they also might help combat both types of bruxism, says Klasser. Because people can learn in their sleep, it wouldn’t even be necessary for an alert to wake up the clencher, he notes. So, in theory, people could learn to battle bruxism as they doze.