How sharks survived the ‘Great Dying’

By leaving their coastal homes, some sharks survived an event that caused mass extinctions of other species

Artist’s drawing of what one of the mini-survivor sharks would have looked like. Notice the tiny teeth and big, hooklike protuberance over its head.

Alain Beneteau 2013/ http://dustdevil.deviantart.com

By Janet Raloff

Ancient, small sharks survived an event that killed off most large ocean species 250 million years ago. Called the Great Dying, this era marked the end of the Permian Period and the beginning of the Triassic. (That Triassic Period is when dinosaurs would eventually emerge.) The survivor sharks did eventually die out, but not until at least 120 million years after the Great Dying. Where their fossils showed up points to how the mini sharks were able to hold on for so long: They hid out.

The Great Dying brought an end to many fish species, including sharks known as cladodontomorphs (KLAD oh DON toh morfs), or clados. But scientists at the Natural History Museum in Geneva, Switzerland, now report unearthing fossils that show some of these mini sharks hung on long after they were presumed extinct.

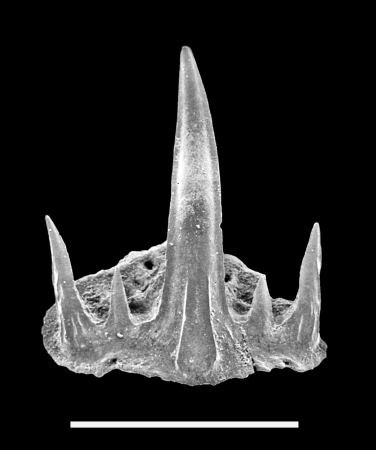

Guillaume Guinot and his coworkers studied fossil teeth from a site in southern France. The teeth came from three species and were tiny: They ranged from almost 1 millimeter to 2 millimeters wide and weren’t quite that long. (That makes them well under a tenth of an inch in any dimension.) Based on their size, Guinot says, these teeth suggest the long-surviving clado sharks would have been small. Adults would have run only about 20 to 30 centimeters (around 8 to 12 inches) long.

For most of their early history, these sharks lived in shallow, coastal waters. After the Great Dying, fossils from such sites showed the clado sharks were missing and presumed dead. The French fossils now show the sharks had just moved to deeper water. The site from where their teeth were retrieved would have been under roughly 150 to 200 meters (some 500 to 650 feet) of water 135 million years ago.

The scientists didn’t have to go diving to find the fossils, Guinot told Science News for Students. The sharks’ teeth were encased in surface limestone near the village of Saint-Hippolyte-du-Fort. Team member Henri Cappetta collected the rock at this site in the late 1980s.

“It took many years to process the sediment,” Guinot says. “As the fossils are very small and delicate and because the limestone is very hard,” this paleontologist explains,

“fossils are recovered by putting pieces of the rock in acid baths.” This unglues the rubble. Once dried again, scientists will shake the debris through a sieve. This will reveal any relatively large objects that had been held in the rocks, such as fossils.

The work was slow and painstaking. Still, it didn’t take 30 years, Guinot admits. Teeth turned up by the sieving were simply put into his museum’s collections and went unstudied.

Guinot says it wasn’t until he was looking for a graduate school research project that anyone focused on those teeth. And even when he got started, he notes, “we were not looking for cladodontomorphs, only modern shark fossils.”

What his team found, though, points to why it’s hard to identify when some species went extinct. These sharks were thought long gone. In fact, he says, it appears they just “used the deep sea environment as a refuge.” From this hideout they could avoid the hostile conditions that ended up killing off so many other species during the Great Dying event. The minis also survived a second, later mass extinction of ocean species.

Fossils from these deep-sea refuges may harbor even more information about how ancient fishes evolved, Guinot’s team says. They described their shark fossils October 29, complete with lots of tooth photos, in Nature Communications.

Power Words

extinction The state or process of a species, family or larger group of organisms ceasing to exist.

fossil Any preserved remains or traces of ancient life. There are many different types of fossils: The bones and other body parts of dinosaurs are called “body fossils.” Things like footprints are called “trace fossils.” Even specimens of dinosaur poop are fossils, called “coprolites.”

graduate school Programs at a university that offer advanced degrees, such as a Master’s or PhD degree. It’s called graduate school because it is started only after someone has already graduated from college (usually with a four-year degree).

mass extinctions Any of several periods in the distant geological past when many — if not most — of the larger animals on Earth disappeared forever. One, sometimes called the “Great Dying,” occurred as the Permian period gave way to the Triassic and led to the extinction of huge numbers of species.

paleontologist A scientist who specializes in studying fossils, the remains of ancient organisms.

Permian A time in the distant geologic past, about 250 million to 300 million years ago. Many reptiles rose to prominence on land; these were not yet dinosaurs. Many large invertebrates ruled the oceans during this period. But most would die off at the end of the Permian, as it gave way to a new geologic period known as the Triassic.

shark A type of predatory fish that has survived in one form or other for hundreds of millions of years. Cartilage, not bone, gives its body structure.

Triassic A time in the distant geologic past, about 200 million to 250 million years ago. It’s best known as the period during which dinosaurs first emerged.