Some seabirds survive typhoons by flying into them

It’s the first time this tactic has been spotted in birds

Streaked shearwaters (one pictured) spend most of their time at sea. There, they occasionally fly through typhoons.

Yusuke Goto

By Freda Kreier

Some seabirds don’t just survive storms. They ride them — heading straight toward passing typhoons.

Streaked shearwaters (Calonectris leucomelas) nesting on islands off Japan sometimes fly near the eye of the storm for hours at a time. This strange behavior has not been reported in any other bird species. Strange as it might seem, it just might help those shearwaters survive strong storms.

Birds and other animals living in areas with hurricanes and typhoons have adopted strategies to weather these deadly storms. Recently, a few studies have tracked ocean-dwelling birds with GPS trackers. They’ve found that some, such as the frigatebird (Fregata minor), take massive detours to avoid cyclones. That’s understandable for birds that spend most of their time at sea, says Emily Shepard. A behavioral ecologist, she works at Swansea University in Wales.

Do shearwaters do something similar? Shepard was part of a team that wanted to figure that out. They used 11 years of tracking data from GPS locators attached to the wings of 75 birds nesting on Awashima Island in Japan.

The researchers combined the bird info with data on wind speeds during typhoons. Shearwaters caught out in the open ocean when a storm blew through would ride tailwinds around the edges of a storm, they found. Other birds found themselves sandwiched between land and the eye of a strong cyclone. These shearwaters would sometimes veer off their usual flight patterns and head straight toward the center of the storm. The researchers shared their findings in the October 11 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Flight path

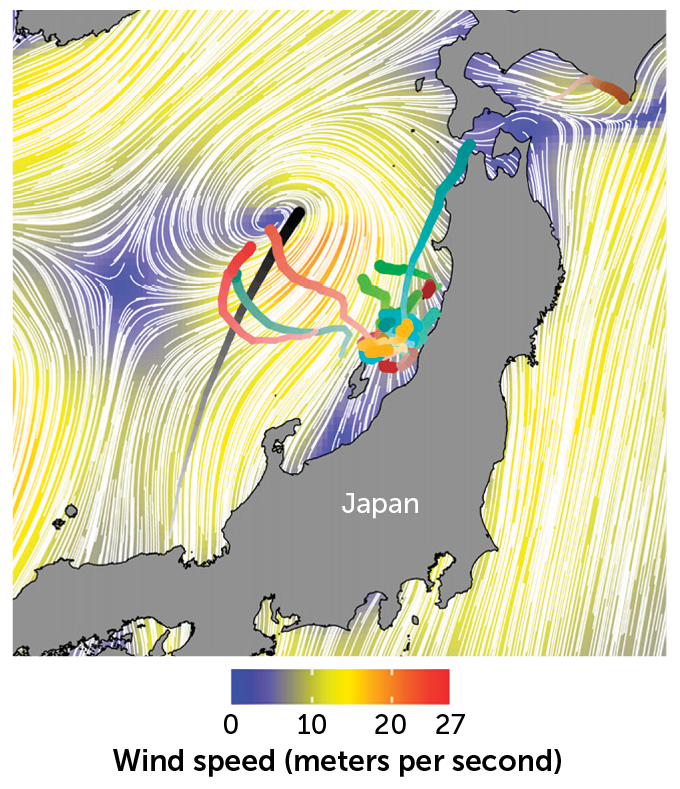

Typhoon Cimaron moved across the Sea of Japan in August 2018 (black track). During that time, GPS trackers monitored the movements of 32 streaked shearwaters just off the coast of Japan. Those tracking data show three birds (seen here in red and teal) flew toward the eye of the storm through some of the highest winds. Two other birds (light green) began heading toward the eye as the storm swept past.

Streaked shearwaters’ movements during Typhoon Cimaron, August 2018

Of the 75 monitored shearwaters, 13 flew to within 60 kilometers (about 40 miles) of the eye for up to eight hours. Shepard calls that area the “eye socket.” That area is where winds were strongest. The birds were tracking the cyclone as it headed northward. “It was one of those moments where we couldn’t believe what we were seeing,” Shepard says. “We had a few predictions for how they might behave, but this was not one of them.”

The shearwaters were more likely to head for the eye during stronger storms. They’d soar on winds as swift as 75 kilometers per hour (47 miles per hour). This suggests the birds might be following the eye to avoid being blown inland. Closer to land, they might risk crashing or being hit by flying debris, Shepard says.

This is the first time this behavior has been spotted in any bird species. But flying with the winds might also be a common tactic for preserving energy during cyclones, says Andrew Farnsworth. An ornithologist, he studies birds at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. He was not involved in the study. “It might seem counterintuitive,” he says. “But from the perspective of bird behavior, it makes a lot of sense.”