How to stop a speeding bullet

Scientists take a close look at a plastic that has Superman’s ability to stop a speeding bullet

gsagi/iStockphoto

A bullet fired into a disk of polyurethane — a type of plastic — may not burst out the other side. In some instances, the bullet will stop in its tracks, frozen by the plastic and sealed inside. How a simple plastic can do this has left researchers scratching their heads. Until now.

Although experiments have demonstrated the plastic’s bullet-braking ability, the scientific explanation for it had remained a mystery, notes engineer Ned Thomas of Rice University in Houston.

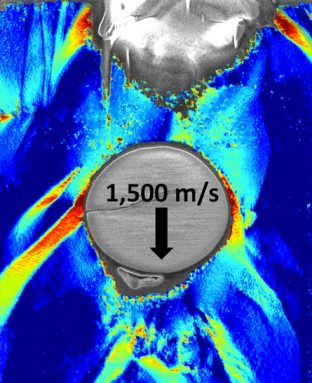

In a new experiment, Rice research scientist Jae-Hwang Lee designed a modified version of the plastic to show what’s happening inside the material when it stops a bullet. The bullets in these tests: glass beads traveling at the breakneck speed of nearly a mile per second. Right now, Lee’s fantastic plastic remains in the lab. But one day, it might find use protecting things that could be targeted by powerful projectiles.

“There may be applications for anything that is impacted at high speeds — body armor, satellites — anything that you don’t want destroyed,” Catherine Brinson told Science News. “This may provide a way to make new materials that are more durable,” she says. A materials scientist at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill., Brinson did not work on the new study.

Liquid polyurethane is a polymer. That means it is formed by linking identical molecules into long chains. Already, this polymer is an ingredient in many paints and varnishes (though painting your walls will NOT make them bulletproof). Hardened polyurethane, also a polymer and similar to its liquid counterpart, looks like a jumble of hard and soft components under a microscope.

Lee developed a simpler, more organized version of hardened polyurethane. His creation resembled a miniature plastic sandwich, alternating thin slices of a glassy polymer with thin slices of a rubbery polymer. Then he and his collaborators, including Thomas, used a device to fire tiny glass beads into the sandwich. On impact, the material went through a weird transformation.

First the layers pressed together, as you might expect. Instead of breaking, however, they seemed to melt and mix like liquids. Then, a millionth of a second later, they were solid again — and the bead was locked inside.

Thomas told Science News that if scientists can figure out how to control this behavior, “we can do extraordinary things.”

Power Words

polymer A substance that has a molecular structure consisting chiefly or entirely of a large number of similar units bonded together in a chainlike structure.

polyurethane A plastic where the carbon-containing molecules are linked through molecules called urethanes, used chiefly as constituents of paints, varnishes, adhesives and foams.

materials science The study of matter, and the creation of new substances.

engineering The application of scientific and mathematical principles to practical ends, such as the design, manufacture and operation of efficient and economical structures, machines, processes and systems.