How to resist and counter today’s flood of fake news

Although misinformation bothers most people, few know how to spot deceit or nonsense

Artists’ representation of a wave of misinformation that threatens to sweep over society and confuse people. Today, legions of researchers are coming up with ways for us to avoid drowning in that misinformation.

Brian Stauffer

From lies about election fraud to bogus anti-vaccine claims, a torrent of misinformation has been flowing through our society. And it is dangerous.

Despite a pandemic, many people have refused to wear masks. It runs contrary to the best available public-health advice. Yet many people have heard some voices say masks aren’t necessary. These people may be misinformed or floating some hidden agenda. But the result is the same. People have gotten COVID-19 who might have avoided it with masks.

And then there are people who have challenged the value of vaccines. In January, some of them disrupted a mass-vaccination site in Los Angeles, Calif. Their actions blocked life-saving shots for hundreds of people.

“COVID has opened everyone’s eyes to the dangers of health misinformation,” says Briony Swire-Thompson. She works at Northeastern University in Boston, Mass. As a cognitive scientist, she studies how the mind performs tasks such as thinking or remembering.

The pandemic has made it clear that in some cases, bad information can kill. And scientists are struggling to stop a tide of misinformation that threatens to drown our news feeds. This flood has been washing across social media with little fact-checking.

Consider a December poll of 1,115 U.S. adults by NPR and the research firm Ipsos. Nearly half (47 percent) of those surveyed believe the majority of Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020 were violent, it found. In fact, the claim was not true. But just a few more than one in every three people (38 percent) knew that.

Scientists have been studying why and how people fall for bad information — and what we can do about it. What they’ve been learning shows that sometimes even small behavior changes can keep us from falling for false claims. By adopting a number of new tactics to staying informed, we can build a dike to keep out the flood of misinformation.

Wow factor

People on social media and elsewhere sometimes share questionable claims because they find them surprising or interesting. How a claim is presented — whether through text, audio or video — also can affect how many people believe and share it.

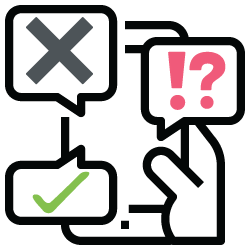

Video tends to seem the most credible, notes S. Shyam Sundar. He works at Penn State University in University Park. There he focuses on the psychology of messaging. He was part of a team that launched a study in response to a series of 2018 murders in India. At the time, people there had been widely circulating a disturbing video via WhatsApp. It falsely appeared to show a child kidnapping.

To test the power of different media, Sundar’s team showed audio, text and video versions of three fake-news stories to 180 people in India. Each story appeared as a WhatsApp message. Viewers with lower levels of knowledge on the topic of the story rated the video stories as most credible. They also were most likely to think those stories worth sharing.

Video sells

WhatsApp users looked at three versions of a story that falsely claimed that rice was being made out of plastic. They did this in (left to right) text, audio or a video showing a man feeding plastic sheets into a machine.

“Seeing is believing,” Sundar concludes. It is also the title of his paper by his team that details their findings. It appears in the August 1 in the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication.

Their findings suggest several ways to fight fake news. For instance, social-media companies could place a higher priority on investigating posts that allege fake news when those posts include video. New programs might also be developed to inform people of how deceptive some videos can be. “People should know they are more gullible to misinformation when they see something in video form,” Sundar explains. That’s especially important with the rise of so-called deepfake technologies. These can feature false but visually convincing videos.

Hard to forget . . . or fully process?

One of the biggest problems with fake news is how easily it gets into our brains and how hard it is to remove once it’s there.

We’re deluged with new claims and ideas. To cope, our minds use mental shortcuts. These help us decide what to remember and what to let go, explains Sara Yeo. She works at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City where she studies science communication. We often find most believable those claims that go along with the values we hold. In other words, she says, people are unlikely to question things that fit with what they already believe.

Making things worse, people can process the facts in some message properly, yet still miss the point it’s trying to make. Why? Our emotions and values can affect how we interpret data, notes Valerie Reyna. She’s a psychologist at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. She wrote about it, last year, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Special report: Awash in deception

The good news: Researchers are developing tools to battle misinformation.

One approach is to “prebunk” facts beforehand rather than debunk them after the fact.

Sander van der Linden is a social psychologist. He works at the University of Cambridge in England. He was part of a team that in 2017 studied what happens when people read true information about climate change, then later encounter a petition that denies the reality of climate science. That petition, they found, canceled any benefit of having first heard the true information. Simply mentioning the bogus claims appeared to undermine what people came to believe was true.

That got van der Linden thinking: Would offering people other types of truthful data before giving them bogus claims work the same way?

In the climate change example, they tested this by telling people ahead of time that “Charles Darwin” and “members of the Spice Girls” were among the false signatories to the petition. This advance knowledge, they found, indeed helped people resist the petition’s bogus claims. It also helped them recall one important message — that there was a consensus among scientists on climate change.

Here’s a very 2021 metaphor: Think of fake news as a virus. Prebunking would be like giving people a vaccine. It would allow them to build up antibodies to bad information.

Van der Linden and his colleagues then came up with a game to help teach people to more broadly spot and fight bogus claims. They call it Bad News. It proved so promising that the team developed a COVID-19 version: GO VIRAL! Early results suggest that playing it helps people better spot bogus pandemic-related claims.

Pause and take a breath

Sometimes slowing the spread of misinformation might just require getting people to stop and think about what they’re doing, says Gordon Pennycook. He’s a social psychologist at the University of Regina in Canada.

In one 2019 study, he worked with David Rand at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. The two showed real news headlines to 3,500 participants. They also showed them fake headlines on political topics. One example: “Pennsylvania federal court grants legal authority to REMOVE TRUMP after Russian meddling.” The researchers also tested the analytical reasoning of the people taking part in this study.

Those who scored higher on the analytical tests were less likely to mistake fake news headlines as being accurate. And it didn’t matter to which political party they might belong. In other words, lazy thinking, not political bias, might drive someone’s acceptance of fake news. Pennycook and Rand reported their findings in Cognition.

How to debunk

Debunking bad information is challenging, especially if you’re fighting with a cranky family member on Facebook. Here are some tips from misinformation researchers:

- To better understand how to spot hoax videos and stories, arm yourself with media-literacy skills at sites such as the News Literacy Project.

- Don’t stigmatize people for holding inaccurate beliefs. Show empathy and respect. When you don’t, you’re more likely to turn off your audience than get them to successfully share accurate information.

- Translate complex — but true — ideas into simple messages that are easy to grasp. Videos, graphics and other visual aids can help.

- When possible, once you provide a factual alternative to some misinformation, explain the underlying fallacies (such as selecting only information with which few if any experts agree; that’s a common tactic of climate-change deniers).

- Speak up when you see misinformation being shared on social media as soon as possible. If you see something, say something.

But when it comes to COVID-19, political leanings do seem to affect how we behave. These researchers talk about it in a paper first posted online April 14, 2020, at PsyArXiv.org. People with strong political views, especially in the United States, tend to get their news from very different media, they showed. And this can overwhelm someone’s reasoning skills when it comes to taking protective actions, they say, such as deciding whether to wear masks during the pandemic.

Inattention, too, can help fake news to spread, Pennycook says. Fortunately, he adds, there’s a simple solution: “We have to stop shutting off our brains so much.”

For debunking, timing can be everything. Tagging headlines as “true” or “false” after presenting them helped people remember one week later whether the information they were hearing had been accurate. It worked far better than tagging them that way before or at the moment the information was shared. That’s according to a February report in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Nadia Brashier is a cognitive psychologist at Harvard University. She worked with Pennycook and Rand on this study. So did political scientist Adam Berinsky at MIT. Prebunking still has value, they say. But providing a quick and simple fact-check after someone reads a headline can be helpful, too. That’s especially true for social media, where people can scroll through posts almost mindlessly.

In the end, it’s clear that much more remains to be done to vaccinate the public against false information. Says van der Linden, “We’re trying to answer the question: What percentage of the population needs to be vaccinated in order to have herd immunity against misinformation?”