Hungry bug seeks hot meal

A seed-loving insect finds food by sensing its temperature

|

|

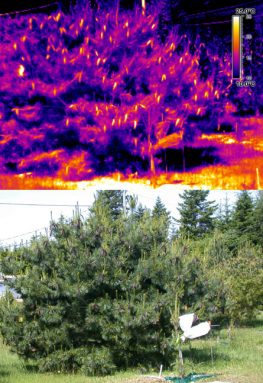

Western white pine cones light up when seen through an infrared camera. Even under cloudy conditions, the cones run 15 degrees Celsius warmer than the surrounding needles.

|

| Photography: Hannah Bottomley; Thermography: Stephen Takács |

Superman may have something in common with one kind of seed-eating bug. Both use special powers to zero in on a warm target. In the bug’s case, the target is dinner.

For humans, finding some Oreos or popcorn can be a challenge in a crowded supermarket. Now imagine how hard it must be for a tiny bug on the lookout for pine cone seeds. The insects have to search among many needles. And there aren’t any aisles with signs.

Recently scientists discovered that a bug that dines on pine cone seeds uses a special ability to seek them out. This insect finds its next meal by sensing the food’s temperature. All living things give off heat in the form of infrared light. While this kind of light is invisible to humans, scientists have found that the seed-eating bug is able to detect it.

When it grows cold outside this cone-loving bug shows up in people’s homes. This got bug scientists thinking. Perhaps the seed-eaters were creeping into homes looking for a warm place to catch some zzz’s. And if the bugs could sense the warmth in homes, maybe they could sense warm food, too.

Scientists know that some plants can generate heat. Skunk cabbages, for example, heat themselves and even melt the snow around them. So the bug scientists thought the seed bugs could be searching for cones that give off some heat.

The researchers took their theory, or idea, outdoors for a test. They brought along a special camera that gave them the ability to see warmth. Through this camera, heat showed up in shades of yellow and orange. When the scientists looked at the pine cones through the camera, the bugs’ food lit up. The trees looked as if they were covered in candles. “All we could think of was Christmas,” said Stephen Takács, the leader of the study and a scientist at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, Canada. “We were just stunned.”

The researchers took the temperatures of different kinds of cones and needles during each season. It turned out the cones were always about 15 degrees Celsius warmer than the surrounding needles. That’s the difference between needing a light jacket and knowing it’s time to break out your shorts. The find was proof enough that the cones were warmer than their environment. Still, the team wanted to explore if the bugs were truly detecting the hotter food.

|

|

Seed-eating bugs armed with infrared detectors zero in on the glow of cones.

|

| Photography Iisak Andreller; Thermography: Stephen Takács |

The scientists hunkered down and watched the bugs search for food in the wild and in the lab. Sure enough, the insects had an obvious preference for cones that glowed especially bright from their warmth.

This is the first time scientists have found a seed-eater with a knack for detecting heat given off by its plant meal, Takács says. Scientists have started to wonder if other bugs have similar skills.

“We tend to focus on things humans can see, can observe easily” explains scientist Irene Terry of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Now scientists are learning that other things help insects find food, she says.

On the bugs’ bodies, researchers found sensors that seemed to be used to find the warm cones. The scientists tested this theory by painting over the sensors with silica paint. This kind of paint blocked the bugs’ sensors from detecting the heat. The team found that, once painted, the bugs no longer hunted for the “lit up” cones.

The scientists also peered inside the bugs’ nervous system, which responds to input from the senses. The researchers found a clear pathway from the sensors to the brain. This connection might be used to tell the bugs’ brains that hot food is directly ahead or, maybe, a little to the left.

Takács isn’t sure why the cones are warm. He thinks the cones may be hotter because bigger objects collect heat better than smaller objects. He says the warmth could also be produced from the energy generated during seed development.

While scientists continue to search for these answers we can be sure of at least one thing. These seed-eating bugs have the skills to find their next hot meal.