Hurdling poverty to find a life in science

Scientists and engineers share how they overcame one big career obstacle — growing up poor

Most students start out fascinated by science. Over time, some might be derailed from the science track by money issues. But they needn’t be. There are plenty of ways to hurdle such obstacles to find a rewarding career in science and tech.

svetikd/iStockphoto

View the video and listen to the podcast

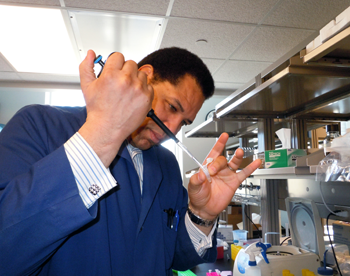

Emmitt Jolly’s father was a janitor in rural Alabama. As a boy, Emmitt helped his dad on some of these jobs. While a student, he also spent time working in tobacco and cotton fields. And he tilled the garden to help grow food for the family dinner table. With no money for college, Emmitt thought he might aim to become an electrician.

In fact, he’s now a molecular biologist at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. His team studies parasitic worms that infect more than 200 million people worldwide. Children infected with these worms often end up weak, poorly nourished and with learning problems. Jolly’s work could someday help prevent or treat the disease these worms cause: schistosomiasis [SHIS-toh-soh-MY-ih-sis].

Jolly beat the odds. He moved from poverty to a successful career in STEM. That acronym stands for Science, Technology, Engineering and Math. On average, people with a college degree earn more than those without one. And STEM careers tend to be among the better paying ones.

Such careers also tend to require at least a college degree, if not graduate studies, which can be quite costly. Many U.S. adults from low-income households do get a college degree. But data show they are only a third as likely to get that degree by their early 20s as are people from families earning the highest incomes. Clearly, poverty creates a hurdle to college for many people, according to data from a 2017 report. (It was published by the Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Education.)

In the United States alone, more than 13 million children and teens are growing up poor. That comes to about one in every six. And poverty is not an equal opportunity affliction. Black and Hispanic Americans are roughly two times as likely as Whites or Asian Americans to be poor. These data come from a September 2017 report by the U.S. Census Bureau.

The high cost of college can be one obstacle to a career in science, tech and math-related fields. But it’s far from the only one, notes Shirley Malcom. She heads education and diversity efforts at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). It’s based in Washington D.C. Poor schools, bad neighborhoods and limited opportunities offer extra hurdles for low-income students.

Yet each year plenty of people overcome poverty to land rewarding careers in science and engineering. It may have taken creativity. Or persistence. Or extra work and patience. But most of them now report it was absolutely worth the effort.

Mentors can be anywhere

If you’re poor, you may not know anyone who works in STEM, notes Malcom. The reason? “Other people in your community are also living hardscrabble lives.” That was true for Abel Chávez as he grew up in Denver, Colo.

Today Chávez works as a civil and environmental engineer at Western Colorado University in Gunnison. His group at Western Colorado aims to make transportation, food production, construction and other activities more environmentally friendly. Over the years, he has worked on engineering projects in Mexico, India, the Philippines and other countries. “I feel that I never work,” he says, because it’s just fun.

As a child, Chávez couldn’t imagine such a career. His dad was a locksmith and mechanic. That didn’t pay well. So his dad also fixed up old cars, then resold them. Chávez’s mom spruced up discarded furniture, which she sold at flea markets. The boy tinkered along with them. “I continually had my hands in something,” he recalls. (Once he even put together a whole car.)

Chávez had few role models outside his neighborhood. Until, that is, a high-school guidance counselor got him into a program with the city’s Rotary Club. That global service group’s members work in a wide range of businesses and professions. The Denver club gave students some money each month, as a reward for keeping their grades up. Abel was among them.

The Rotary Club program also assigned the teen a mentor — someone to encourage the boy and help him see what prospects he might work toward. This doctor treated Chávez to ballgames, restaurant trips and other outings. More importantly, he introduced the boy to people who could help guide him to college. They also steered him toward scholarships to help pay for that higher education.

Starting this summer, Chávez will become dean — a leader — of his university’s graduate school.

Mentors have helped many disadvantaged people. They can play an outsized role for people who live in neighborhoods that offer little insight into people, jobs and issues outside their own community. And great mentors can show up in the most unexpected places.

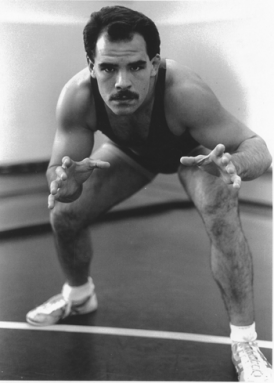

Esteban Burchard found his through sport.

Racism and bullying got Esteban into fights at his first high school. Eventually, he got kicked out. At the next school, Esteban joined the wrestling team. He thought it might help him fight better. Today he looks back and concludes: “Wrestling saved my life.”

That’s because the coach taught more than wrestling. He helped his athletes gain self-confidence and discipline. Those skills helped Esteban do well in school. The teen kept wrestling in college. Through this sport he met even more role models. He also learned to seek guidance from his teachers and others. That continued when he went to medical school at Stanford University in California and then to Harvard Medical School in Boston, Mass. (That last one is where he went for residency training and another degree in public health.)

Now a lung specialist, Burchard works at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). There, he studies racial and ethnic differences in asthma. That lung disease hits minorities and poor people the hardest. Burchard has a special interest in those groups. He grew up poor in San Francisco’s Mission District. He never knew his dad. His single mom worked long hours as a teacher. Her salary didn’t stretch far for their family of five.

Even today at USCF, Burchard seeks guidance from mentors. Interestingly, some of them also wrestled back in school. Burchard also pays it forward by mentoring others. His lab group includes teens from low-income families. Some of these students are the first in their families to go to college.

Help may have to come from inside you

Jolly’s family struggled to make ends meet. Yet he grew up in a loving home. No one tried to stop his studying. Laura Martinez faced a different home life. “I grew up in an environment where there was a lot of domestic abuse and violence,” she recalls. Life at home was bleak.

People at any income level may encounter domestic violence and other types of abuse. But the stress of poverty can make outbreaks of violence more likely. What’s more, people in poor communities may not know where to turn for help.

Even if someone’s family doesn’t face such problems, poor families may live in challenging neighborhoods. Fears about safety can stress students. So can the chaos of big or noisy home lives. It’s something Martinez encountered growing up in a family of six who all shared a one-bedroom apartment. “There was no place to go,” she recalls, so “I would try to study in the bathroom.” Martinez also tried to protect her mother from domestic violence.

This only added to the girl’s stress.

Looking back, the scientist now realizes that “A child in middle school should not feel responsible for trying to solve the problems that the parents have.” Society, she says, must teach kids that when any situation becomes dangerous, trusted adults will help: “We don’t have to do it alone!”

A ninth-grade English teacher urged Laura to think about college. The girl liked science and math. Her volunteer work at a local hospital made her think about a career in some medical field. With her mom’s support, the teen came to see that her education was one way to eventually help her mom and siblings.

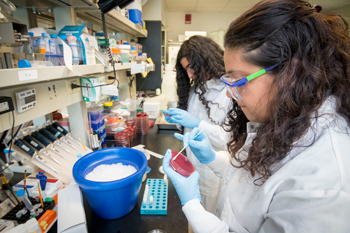

Martinez went on to get her PhD. Now a microbiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), she’s part of a team studying Zika. This mosquito-borne infection can cause birth defects. Martinez’s group wants to know, among other things, why Zika sometimes causes eye disease in babies.

Whoa! Not prepared for college?

Half of Tracie Delgado’s high school class dropped out before graduation. The school was in a poor neighborhood southeast of Los Angeles. The girl had taken honors chemistry there and got into UCLA for college. But in her first college chemistry class, she realized: “I don’t even know what they’re talking about.”

Her high school had not prepared the teen for this class. Her school had fallen short in other ways, too. “You have to learn study skills. You have to work with study groups. You have to learn how to read the material and manage your time,” she explains.

Having not learned that, the girl dropped her chemistry class.

But she didn’t give up.

She got mostly C’s that first year of college. She’d need better grades if she hoped to go further. So she knuckled down and learned how to study. By the last year of college, Delgado was mostly an A student.

She went on to graduate school and today is a microbiologist at Northwest University in Kirkland, Wash. She studies how viruses cause cancer. That work could lead to new treatments for cancer and other infections.

Don’t be afraid if you don’t succeed right away, she tells Science News for Students. “Winners are not people who never fail — because I definitely failed.” What allowed her to succeed, Delgado says, is that “I just never gave up.”

This is something that education researchers refer to as “grit.”

Fortunately, Miquella “Kelly” Chavez also had this grit.

In high school, the small-town girl from New Mexico never got the message about preparing for college. She intended to go. She even got accepted. But no one had taught her how to apply for scholarships. So when the teen saw how much a four-year college was going to cost, she gave that up. Instead, she enrolled at a two-year community college. After trouble in her personal life, she took time off from school and worked at a gas station.

When she started classes again, money was still tight. Now, she also had to help care for her dad. Along the way, a campus job gave her hands-on experience in research. Kelly Chavez ran tests to see what proteins were in “slimy little animals” that researchers had collected near the Mexican coast.

“Everyone there was friendly,” she says. What’s more, they were having fun doing science. Still, she recalls, “it didn’t click” that she could go on to graduate school. So after college, Chavez worked in a lab at the university’s health sciences center. It was there that a supervisor persuaded her to get her PhD.

“I’m happy with my life now,” she says. Chavez manages a materials research and engineering center at Duke University in Durham, N.C. The center’s research teams study soft matter — “basically anything squishy.” One example is the polymers in contact lenses.

Isis Frausto-Vicencio also had a bumpy ride to her research career in atmospheric chemistry. Recently, her team mapped emissions of methane in California. As a greenhouse gas, methane promotes global warming. So knowing where releases of it come from is a big step toward controlling them. However, coming from a family of farm laborers, Frausto-Vicencio had never imagined such a career for herself. Indeed, the day after high school graduation, she was back in the farm fields with her dad. “I was picking grapes.”

Her family had moved a lot. Because of several years at rural Mexican schools, the girl had lots of catching up to do. But the idea of college always appealed. Finishing it took her six years, not the usual four. Now she’s a graduate student at the University of California, Riverside.

As Kelly Chavez notes, the path to a career in science may not be straight. Things may be hard. You may fall off the path you first embarked upon. But there’s no shame in having to take a detour: “It’s okay to fall down and pick yourself up and keep going.”

Coping when the money just isn’t there

Jolly had been offered full scholarships at four colleges. Most students — even very good ones — aren’t so fortunate. Diogenes “Dio” Placencia was one of those not-so-lucky teens.

His dad died when he was a baby. His mom worked long hours in New York City’s garment district. When he got into Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Conn., he qualified for only a partial scholarship. To make ends meet, the teen and his mom took out loans. Placencia also worked on campus in the chemistry department. With that, he could make ends meet — until another student went back on a deal to share an apartment. It was in his last year of college. Dio did not have enough money to pay for the place all on his own.

So Placencia got creative — and relied on his grit. “I basically went through an entire academic year sleeping in a lab,” he says. He camped out there on weekday nights. He showered at the college gym. On weekends he worked three 12-hour shifts at an environmental lab in New York City. Meanwhile, he took extra courses so that he could finish his undergraduate and master’s degrees at the same time.

When he went on for a PhD, the tables turned. The school paid his tuition and a bit more. That’s common in many STEM fields, notes Malcom at the AAAS. When you reach that level, she notes, “You don’t pay the school. They pay you.”

Now Placencia is a research chemist for the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C. He works to develop better materials for cameras, sensors and other equipment for people in the armed forces. Specifically, he studies interfaces. “You slap two materials together, and you look at what happens electronically between them,” he explains.

Starting this summer, he’ll also head up a science program at the U.S. Consulate in Sao Paulo, Brazil. The program promotes cooperative research between the United States and scientists across Latin America.

Story continues below video and podcast.

Adam Dylewski/Explainr

Listen to a longer version of this interview here:

Placencia worked a wild schedule to finance the educational path to this career. Some people instead get help from the military. In return for serving, the U.S. Army, Navy and other branches may pay for college. Ashley McCormack had already worked at multiple jobs to get through college. Then she joined the Army. She now feels “it was the best and worst decision I ever made.”

Basic training was grueling. On the other hand, the Army let her do research in a medical lab. It also paid for her to complete a master’s program.

She now works as a molecular biologist for a government contractor at the National Institutes of Health in Rockville, Md. She loves being part of a large research team. Her group is looking for ways to keep mosquitoes from being infected by the parasites that cause malaria.

Seeing the world differently

Martinez thinks those who grew up poor can bring a lot to STEM fields. “You have been challenged financially. You have learned from those experiences. And you have managed to get through those experiences in practical, resourceful ways,” she says. That talent can provide an edge for success in science and engineering.

Along the way, young people can grow and learn a lot about themselves. For example, many people who grow up poor are taught that asking for help “is asking for a handout,” Kelly Chavez notes. She disagrees. Many programs exist to help people in need. Taking advantage of them is just using those programs for their intended purpose. And often people are willing to help if you’re willing to do the work to follow through. Indeed, scientists and engineers very often ask each other for help on the job. Science is in many ways a team sport.

Students also may feel that spending money on their education instead of other family needs is somehow selfish. Frausto-Vicencio admits “there was always that guilt.” By going to college, she wondered if she “was being selfish” — not helping her family enough. Even today, she says, “I have to tell myself I deserve to be in this place.”

Now that he’s succeeded, Jolly is encouraging other young people living in poverty to consider STEM careers. Yes, he admits, financial pressures can pose big problems. But most people face problems of one sort or another. As Jolly sees it, “You can mope or you can do something about it.” He advocates taking action.

And one payoff just may be a truly rewarding career.

This is part of a Cool Jobs series on the value of diversity in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. It has been made possible with generous support from Arconic Foundation.