astronomy The area of science that deals with celestial objects, space and the physical universe. People who work in this field are called astronomers.

astrophysics An area of astronomy that deals with understanding the physical nature of stars and other objects in space. People who work in this field are known as astrophysicists.

atmosphere The envelope of gases surrounding Earth or another planet.

exoplanet Short for extrasolar planet, it’s a planet that orbits a star outside our solar system.

focus The point at which rays (of light or heat for example) converge sometimes with the aid of a lens. (In vision, verb, "to focus") The action a person's eyes take to adapt to light and distance, enabling them to see objects clearly.

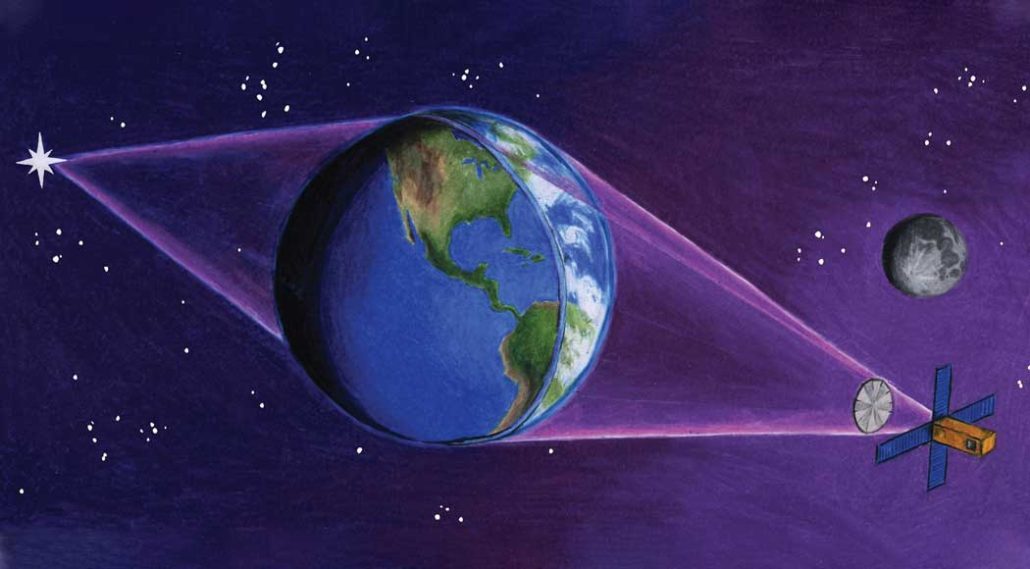

lens (in optics) A curved piece of transparent material (such as glass) that bends incoming light in such a way as to focus it at a particular point in space. Or something, such as gravity, that can mimic some of the light bending attributes of a physical lens.

NASA Short for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Created in 1958, this U.S. agency has become a leader in space research and in stimulating public interest in space exploration. It was through NASA that the United States sent people into orbit and ultimately to the moon. It also has sent research craft to study planets and other celestial objects in our solar system.

observatory (in astronomy) The building or structure (such as a satellite) that houses one or more telescopes.

planet A celestial object that orbits a star, is big enough for gravity to have squashed it into a roundish ball and has cleared other objects out of the way in its orbital neighborhood.

propulsion The act or process of driving something forward, using a force. For instance, jet engines are one source of propulsion used for keeping airplanes aloft.

range The full extent or distribution of something. For instance, a plant or animal’s range is the area over which it naturally exists. (in math or for measurements) The extent to which variation in values is possible. Also, the distance within which something can be reached or perceived.

refract (n. refraction) To change the direction of light (or any other wave) as it passes through some material. For example, the path of light leaving water and entering air will bend, making partially submerged objects to appear to bend at the water’s surface.

star The basic building block from which galaxies are made. Stars develop when gravity compacts clouds of gas. When they become dense enough to sustain nuclear-fusion reactions, stars will emit light and sometimes other forms of electromagnetic radiation. The sun is our closest star.

telescope Usually a light-collecting instrument that makes distant objects appear nearer through the use of lenses or a combination of curved mirrors and lenses. Some, however, collect radio emissions (energy from a different portion of the electromagnetic spectrum) through a network of antennas.