Identifying as a different gender

As children make gender transitions at younger ages, the real difference is growing public acceptance

Sometimes a child grows up “knowing” that their gender is not the one that others have outwardly seen them as since birth. But with the love and support of their family and community, these children can grow up feeling happy and healthy.

Illustration by James Provost

Second of two parts

Christopher. Emma. Adedeji. I-Ling. Sunjay. Drazen. A name says a lot about what parents see in their child. For one, names almost always announce whether their new bundle of joy is male or female. That determination usually is made based on a newborn’s anatomy.

But whether it’s a girl or boy, the anatomy does not explain all. That’s because there is more to a child’s sex and identity than first meets the eye. This is especially true for a small percentage of individuals. In them, gender identity and what they look like won’t truly match. From an early age, these might even collide.

Last week we met Zoë MacGregor. Though born as Ian, an apparent boy, Zoë began showing signs that she identified as a girl as early as age 3. By age 9 she transitioned into presenting herself as a girl. Here, transition refers to changing one’s name, behavior and dress so that they match one’s gender identity.

There is no typical age for a gender transition. And there is still a great deal of discrimination toward people who announce a new gender identity. Transgender is the term used to describe someone living as the gender opposite to the one assigned at birth.

Public acceptance of transgender individuals is growing. And as it does, children are making their gender transitions at younger ages. Some children go through transitions as early as elementary school — even preschool. Still, it is not unusual for people to transition as teens or adults. In March of this year, for instance, 65-year-old Bruce Jenner announced he was transitioning to womanhood as Caitlyn. This former athlete had won a 1976 Olympic gold medal in the decathlon (still a men’s-only event there).

Facing uncertainties

Dysphoria (Diss-FOR-ee-ah) is a medical term used to describe a state of unease. Gender dysphoria is a recognized medical condition. It refers to feeling that one was assigned the wrong gender at birth. Naturally, parents want to do what is best for their children. But helping a child navigate gender dysphoria can be hard.

The quality of life that affected individuals face can vary a lot. One 2011 report surveyed 6,500 transgender individuals. Four in every 10 reported having attempted suicide. (That’s 38 times the rate in the general population). Research suggests that a major reason for this is the misunderstanding and disrespect that transgender people can suffer from their peers, classmates — and even members of their family.

Leelah Alcorn of Kings Mill, Ohio, took her life in December 2014. She was assigned a male gender at birth and given the name Joshua. In a suicide note posted on her blog, the transgender 17-year-old wrote that since the age of 4 she felt “like a girl trapped in a boy’s body.” And she said it hurt that her parents rejected her female identity to the extent that they put her into a therapy with the aim of changing her mind.

More and more, research shows that for everyone, support and acceptance from their family and community can greatly influence their mental health and happiness.

A small 2014 study also found evidence of this among transgender youth. This research looked at five mothers of transgender daughters. At birth, these children had been listed as males. But between the ages of 7 and 10, all transitioned socially to living as girls. How much they had been accepted — or rejected — by their families, their schools and their communities seemed to play a big role in how well-adjusted and happy these children were, the study found.

That study was part of a larger, long-term one. It is now following 49 families with transgender and gender-nonconforming children. (Gender-nonconforming describes people who do not dress or behave in a way typical of their assigned gender. Not all of these people will consider themselves transgender.)

“Family acceptance has a critical role to play when it comes to the well-being of these children,” says Katherine Kuvalanka. She is leading the study. A family-studies researcher at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, her work focuses on transgender issues.

Families often report that when they allow their children to transition, “the kids then blossomed as if a light has turned on,” Kuvalanka says. They look as if “a great weight has been lifted from their shoulders.” Still, family acceptance isn’t always enough. “These children also need support and acceptance from their schools, peers, religious leaders and other influential people and social institutions in their lives,” she says. Yet people in these positions often are unsure how best to support transgender people.

Turning points

The lack of long-term research on transgender identity poses serious challenges for affected children and their parents.

Deciding how and when a child should transition “is a tough decision for parents. And parents do often rely on experts,” says Kristina Olson. She works at the University of Washington in Seattle. As a developmental psychologist, she studies how people change as they develop from infancy through young adulthood.

“We know very little about transgender youth,” she says. One reason, she admits, is that “for a long time they were kind of ignored by scientists.” And the few scientists who did pay attention sometimes viewed transgender youth as so unusual that they wanted “to understand what’s wrong with them.” The goal of those scientists, she says, had been to learn what it would take to make these children “right” again.

That view is fading. To better understand transgender children, Olson launched the TransYouth Project in 2013. It includes both transgender children and, when possible, other family members. Both Zoë and her younger sister are taking part.

Early in Zoë’s journey, her parents joined a support group. It brought them together with other families of transgender individuals. Through the group, they learned that every transgender individual does not follow the same path.

Before long, Zoë’s parents were asking themselves: How far does our child want this to go? Carolyn, the girl’s mom, remembers asking: “Is [Zoë] going to feel it’s necessary to take the step of transitioning? Or will she be comfortable being this boy who likes girl things? Where is that line for her?”

With time, that line became more clear.

In December 2013, soon after turning 12, Zoë’s life entered a new chapter. She started taking drugs that block puberty. Called puberty inhibitors, they suppress the hormones that made Zoë’s anatomy look like a boy’s. The drug treatment put on hold those body changes that start to occur at the onset of puberty — usually between the ages of 10 and 14.

A doctor implanted a controlled-release drug into Zoë’s upper arm. About the size of a matchstick, it releases tiny amounts of a medicine called histrelin (HISS-treh-lin). Every year or two, doctors will have to replace it. The drug will keep Zoë’s body from producing increasing amounts of male sex hormones, especially testosterone (Tess-TOSS-tur-own).

That hormone spikes in males during puberty. Suppressing it would keep Zoë’s voice from deepening and an Adam’s apple from forming. She also wouldn’t develop facial hair and other typically masculine features. (For people who outwardly appear female at birth but want to live as a male, other puberty blockers will halt breast development and prevent menstruation.)

“We know that going through the ‘wrong’ puberty can be extremely damaging for many of these kids,” says Johanna Olson. She directs the Center for Transyouth Health and Development at Children’s Hospital in Los Angeles, Calif. “The risk of suicide is incredibly high,” she notes.

“With hormone blockers — drugs that have safely been used in other contexts for a very long time — we can hit the ‘pause’ button on puberty.” These hormone blockers allow people time to explore their identity without progressing further toward either male or female sexual development, Olson explains. “Transgender teens facing an undesirable puberty are often so preoccupied with impending body changes that they cannot participate meaningfully in school, family, peer, and therapeutic environments.”

Drugs that block the natural progression of puberty are reversible. If Zoë stopped taking hormones tomorrow, for instance, her body would begin producing normal amounts of male hormones. That would restart the emergence of male features. But soon, Zoë and her family will face a bigger decision: whether to begin taking cross-hormones.

These would lead to more drastic body changes. Over time, for people who transition from male to female, these hormones would feminize their bodies. For instance, breasts would now develop and the features on their faces would soften. Their bodies also would redistribute fat cells to areas such as the hips and thighs. This tends to create a curvy figure. Some transgender people take the physical transition even further. They undergo surgery to achieve the anatomy of the gender with which they identify.

Carolyn says that Zoë is eager to begin taking female hormones. Her daughter is aware that her girlfriends are developing womanly attributes that Zoë never can without hormones. “I think that’s been the hardest thing for her,” Carolyn says, “Feeling a little out of step.”

But Zoë’s taking cross-hormones weighs heavily on Carolyn. It will affect her child’s fertility. It would likely make it impossible to father a child if Zoë were ever to live again as a male. “That, to me, is probably the scariest part of this,” Carolyn says. “No matter what we choose, there’s always the possibility that it’s the wrong thing.” Still, Carolyn feels confident that she and Zoë’s father have listened closely to their child every step of the way.

Support networks

Aidan Key is executive director of Gender Diversity. This Seattle-based group is dedicated to increasing the understanding of gender issues. An educator, Key has focused on concerns related to transgender children. There are uncertainties in how well transgender children will cope with what life throws at them, he notes. And it’s something he personally understands all too well.

Key was raised a female. Yet from childhood he had felt he was male. Key remembers feeling that both his mother and his twin sister supported him. Still there were times he was told to wear clothes in which he felt uncomfortable. Putting on a dress for church or other special occasions always felt like donning a “costume.” But unlike dressing up for Halloween, he explains, this costume was no fun.

From the age of 9, he says, “I started realizing that the path put in front of me was very different from the path that I felt was right for me.” In his mid-30s, he made a gender transition. That was about 18 years ago. Today he has a wife and daughter.

Key has helped hundreds of families navigate transgender issues, including Zoë’s. There are no certainties about what will be right for any one of them, Key points out. Still, he likes to emphasize what he believes transgender research makes clear: that a family’s support is crucial. When these kids receive their family’s support, he says, especially before puberty, “they’re going to have less stressful childhoods.” It is important that these kids “receive those messages from their family that they are loved, that their family thinks that they’re amazing and beautiful for exactly who they are.”

Some kids might indicate they feel they are the opposite gender. Others might simply be attracted to belongings of the opposite gender. For example, a boy might be drawn to glittery, Hello Kitty backpacks. That doesn’t necessarily mean he is transgender, Key cautions.

That’s why he counsels parents to listen to their children closely. It’s a parent’s job, Key stresses, “to establish an environment where that kid can freely communicate and feel loved and respected as they do. You just can’t go wrong with that.”

And when a child genuinely identifies as transgender, this does not necessarily mean that he or she has to go through a transition. Many families worry about whether it would be right for their child. What if their child later changes his or her mind? Should parents therefore hold off making any decisions until their child is older?

In fact, Key argues, there is no one “right” outcome. “If you open the door to allow a child’s gender exploration, in the same way that you would open the door for scholastic pursuits or artistic pursuits, kids are going to find their way.”

See part 1: Gender: When the body and brain disagree

Editor’s note: This article was edited on April 29, 2024, to remove two paragraphs about the work of Kenneth Zucker due to lack of supporting evidence.

Power Words

(for more about Power Words, click here)

anatomy (adj. anatomical) The study of the organs and tissues of animals. Or the characterization of the body or parts of the body on the basis of its structure and tissues. Scientists who work in this field are known as anatomists.

biological sex This refers to our biological and physical anatomy, which is used at birth to assign gender. In some cases, biological sex and gender are not aligned.

controlled-release system A material or device that allows small quantities of some compound to slowly enter the environment (or even the human body) at a rather regulated rate. Some drug implants work this way, slowly release a drug into the bloodstream or specific tissues over time. Other controlled-release systems might dispense a chemical into the air or soil.

cross-hormone (hormone replacement therapy) Male or female sex hormones that inspire the development of physical characteristics of the desired gender.

development (in biology) The growth of an organism from conception through adulthood, often undergoing changes in chemistry, size and sometimes even in shape.

fertility Ability to reproduce.

gender dysphoria The formal diagnosis given to people whose assigned birth gender is contrary to the one they identify with. The word dysphoria describes a state of unease — the opposite of euphoria.

gender identity A person’s innate sense of being male or female. While it is most common for a person’s gender identity to align with their biological sex, this is not always the case. A person’s gender identity can be different from their biological sex.

gender non-conforming Behaviors and interests that fall outside of what is considered typical for a child or adult’s assigned biological sex.

hormone (in zoology and medicine) A chemical produced in a gland and then carried in the bloodstream to another part of the body. Hormones control many important body activities, such as growth. Hormones act by triggering or regulating chemical reactions in the body.

hormone blocker Medications used to suspend the development of puberty.Some environmental pollutants may also bind to hormone receptors and block their action. These too may suppress the development of a male or female, potentially lending them traits typical of the sex expected based upon their genetic inheritance.

inhibitor A material or action that slows or stops something, such as a drug that might halt a chemical reaction in the body.

peer Someone who is an equal, based on age, education, status, training or some other features.

psychopathology The study of mental disorders.

puberty A developmental period in humans and other primates when the body undergoes hormonal changes that will result in the maturation of reproductive organs.

scholastic An adjective for things that relate to schools or eduction.

support group People who choose to meet and describe how they are coping with a common source of stress and uncertainties, such as dealing with a disease in themselves or a family member.

testosterone Although commonly thought of as a male sex hormone, females also make this reproductive hormone (generally in smaller quantities). It gets its name from a combination of testis (the primary organ that makes it in males) and sterol, a term for some hormones. High concentrations of this hormone contribute to the greater size, musculature and aggressiveness typical of the males in many species (including humans).

therapy (adj. therapeutic) Treatment intended to relieve or heal a disorder.

transgender Someone who has a gender identity that does not match the sex they were assigned at birth.

transition (in gender studies) A term used to describe the process of changing one’s outward gender in terms of name, behavior, expression and/or body to match one’s gender identity. A transition may be social, physical or both.

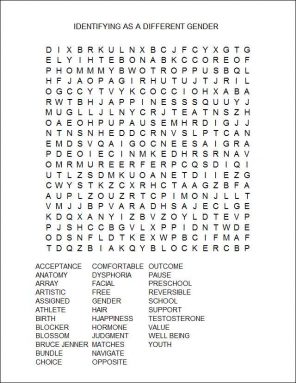

Word Find (click here to enlarge for printing)