Implant traps cancer cells on the move

Husband-wife team creates implant to catch migrating cancer cells before they form new tumors

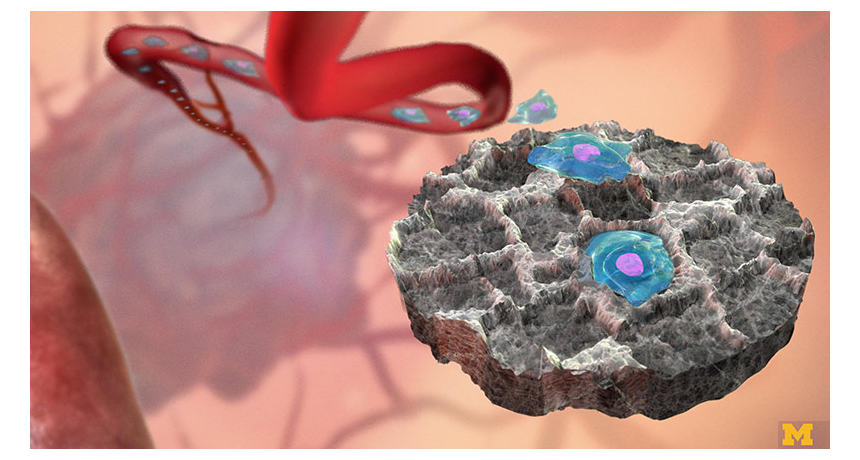

In mouse experiments, this small implanted device helped catch breast cancer cells (shown in blue-green and purple) before they took root in other organs.

Gabe Cherry

A cancerous lump in the breast can be dangerous, but it seldom kills. However, if cancer cells leave that lump, the satellite tumors that form in other organs pose a much bigger threat. And those tiny new cancers can be hard to spot. Now, a study shows that implanting a small device beneath the skin might help save lives by catching cancerous cells after they begin wandering — but before they settle down to form new tumors.

The implant has not yet been tested in people. But when placed into mice with tumors, the device trapped runaway cancer cells. These cells are known as metastatic (MET-uh-STAT-ik) cells. They signal worsening disease. And the mice lived longer when researchers cut away the tissue around the implant, where those metastatic cells had been lurking.

A team at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor reported these findings September 15 in Cancer Research.

The invention has “a lot of potential,” says breast surgeon Charusheela Andaz. “It’s a novel idea.” Andaz, who did not help with the study, works at Maimonides Medical Center in New York City. The new implant could be useful in people at risk of breast cancer — or in patients who have been treated successfully but whose cancer could return, she suspects.

Surgeon Jacqueline Jeruss is one of the new study’s authors. She gets sad and frustrated when a patient’s breast cancer spreads to the lung, liver, bone or brain. For years her husband, Lonnie Shea, listened to her talk about how bad she felt for such patients.

Shea also works at the University of Michigan. As a chemical engineer, he uses chemistry to create useful products. He and Jeruss thought about patients whose cancer had been cured but could return. It’s as though those patients have a “ticking time bomb,” Shea says. “The cancer could come back, but they don’t know when.”

That idea inspired the couple to develop the new cancer-catching implant.

Decoy device

As the duo brainstormed, a long-held theory came to mind. Some researchers believe that as cancers begin growing in the breast, they tend to stay put. “They haven’t found a way to grow up and leave home yet,” says Jeruss. “They haven’t yet received the education to fly out of the nest.”

Eventually, some young cancer cells may start to roam. They don’t just wander randomly, however. They tend to go where conditions are best for resettling. Scientists don’t know everything about what makes the new sites attractive to migrating cancer cells. But they know that such sites contain immune cells — part of the body’s defense against infections and foreign invaders. Those immune cells in turn lure cancer cells that are on the move.

Jeruss and Shea’s new device is about the size of a pencil eraser. It’s made of the same material as the stitches that doctors use to sew up wounds. Since immune cells are programmed to recognize foreign material, they flock to the implant. There they act “like a decoy,” Jeruss says. They build up around the implant and lure metastatic cells.

Last year Shea and Jeruss did mouse experiments to show the implant could attract metastatic cells. The new study took things further by showing cancer-bearing mice with the implants live longer.

In the new tests, half of the mice received implants. One month later, all of the animals received an injection of breast cancer cells. Ten days after that, the researchers did surgery to cut out the animals’ tumors. Another five days after that, they checked each mouse’s liver and brain. Breast cancer cells often migrate to these organs. But in the mice with implants, 64 percent fewer cancer cells spread to the liver, and 75 percent fewer made it to the brain. Four in every 10 of the animals with implants were still alive six months later. In contrast, all of the mice without implants died within 40 days of the removal of their tumors.

Another pleasant surprise: Cells trapped by the implant did not form new tumors.

The researchers hope to test their device in people soon to see if the implant is safe and attracts cancer cells as it did in mice. The team also could retrieve cells from participants’ implants. Back at the lab, the researchers could study those metastatic cells to figure out what’s special about them, Jeruss says. For example, they could look for unique genes and proteins that are in these cells but not in cancer cells that do not metastasize. Those insights might help the team develop new cancer-fighting therapies that are tailored to tackle the most troublesome cells.

This is one in a series presenting news on technology and innovation, made possible with generous support from the Lemelson Foundation.