Infectious animals

Critters spread many germs that can sicken each other — and even kill people

Jonathan Epstein studies how diseases are transferred between animals and people. This bat, Pteropus giganteus, commonly carries Nipah virus. The germ killed hundreds of people and more than one million farm animals.

ECOHEALTH ALLIANCE

When people talk about catching the flu, most consider classmates, family members or neighbors as likely sources. So it might be surprising to learn that the viruses we get a flu shot for each year originate in birds, not people. Birds can spread flu not only to other birds, but also to livestock and people (which then spread the virus among their own kind).

Like all viruses, influenza — or flu, for short — can live only within an organism. Scientists call that animal the germ’s host. Over time, some animals become long-term hosts, and often no longer become sickened by the germs. When a virus commonly lives inside an animal without harming it, that host is called a reservoir. Birds, particularly ducks, have evolved to become a natural reservoir for flu viruses.

There are many different versions, or strains, of flu. Most emerge in Asia, where many people raise poultry. Some keep chickens and ducks in their backyards or roaming around in rural villages. Others produce these birds on large-scale farms. In each place, these farmed birds can mix with wild birds. Such a mingling allows viruses to jump from one host into a new one. Migrating wild birds can then carry these viruses with them, making world travelers of their germs.

Animals newly exposed to the viruses may become ill and die. When poultry farmers handle a sick or dead chicken, the virus may find yet another host — people.

All viruses mutate — or change — when their genes develop slight alterations over time. These tweaks occur at random as a virus makes copies of itself inside its host. Flu viruses also alter their genetic makeup by swapping genes with other viruses. The changing nature of viruses makes it challenging for scientists and health officials to create appropriate vaccines that outwit these microbes and keep them from spreading.

“The reason we have different strains of flu every year is because there’s constant change in these viruses,” explains Jonathan Epstein. A veterinary epidemiologist, he’s a scientist who studies the spread of disease in animals. He works at EcoHealth Alliance in New York City. This international organization focuses on the connections between human and animal health and the environment.

Epstein and other researchers are searching for clues about how infectious germs travel from animals — whether wildlife, livestock or pets — to people. Scientists refer to such diseases as zoonotic (ZOO oh NOT ik). And understanding their impacts is important: Half of all germs known to cause human disease come from other animals. And nearly 75 percent of new, or emerging, infectious diseases in people are zoonotic. In other words, germs responsible for most of the new diseases that spread among people were first spread by animals. These microscopic invaders, also called pathogens, take many forms. They not only can be viruses, but also bacteria, fungi and even teeny-tiny worms and head lice.

Kristine Smith, a wildlife veterinarian, points out that it is important not to blame wildlife for diseases. Instead, we should be aware of the risks of being in close proximity to animals and adjust our behavior. “I never want people to think wildlife are nasty things that have all these diseases — it’s not about that,” says Smith, who works for EcoHealth Alliance. “It’s about how we interact with them,” she cautions, that can allow animals diseases to spread into people.

Understanding how pathogens get a foothold in animal or human populations can help scientists not only combat current disease outbreaks, but also predict future ones and prevent or lessen their spread.

Detective work helps

Ian Lipkin works with Epstein and other scientists around the world to identify where viruses might emerge in human populations. Lipkin is a virologist, or scientist who studies viruses, at Columbia University. Researchers like Lipkin and Epstein survey critters to understand what diseases are making animals sick. This way, if some new pathogen appears in people, Lipkin says, the medical community will have some notion of how it spreads and sickens. Then, he adds, researchers may stand a chance of developing a vaccine to slow its spread.

“The idea is that you want to get out in front of the crime,” says Lipkin.

Vaccines are typically made from the germs that cause an infectious disease. They contain part of the germ, or the whole — but dead — germ. When we are injected with this material, our bodies recognize that it is foreign and potentially dangerous. Our immune system is alerted and prepares to fight the germ. It turns out they don’t have to fight too hard, because it’s not a live germ. But in the process of revving up to fight it, the body develops a resistance to that disease. And when we next encounter the real thing — the live germ — our body is primed to kill it.

Some vaccines are administered only once a decade — or even once in a lifetime. For other diseases, like flu, doctors encourage people to get a vaccination every year. The main reason for that: Flu germs change so often and so much that the vaccine prepared in one year may no longer be effective against the flu germs circulating among people the next year.

Alas, vaccines aren’t available for many diseases. To control these, scientists have to develop other techniques. And that’s one reason researchers around the world are taking a close look at how animals and people interact. A better understanding of how we share our lives with other creatures can help reduce how often we also share deadly germs.

Too close for comfort

Farming, forestry (planting and harvesting trees), hunting and even handling exotic pets put us in close, frequent contact with animals. Such activities “allow these pathogens to jump from their natural reservoir into people,” notes Epstein. “And that’s when disease occurs.”

Microbes move among hosts continuously, he explains. Many will encounter a human host whose immune system has never encountered this bug before. That person will have no immunity built up to fight the germ. That lucky germ can now spread, infecting this person. If it survives long enough to be spread to yet another person, Epstein says, it will in effect have won the lottery.

Epstein specializes in viruses whose reservoir is bats. He has been on the trail of numerous viruses that have spilled over from bats and taken hold in people. One notable example: SARS, or severe acute respiratory syndrome, which killed 774 people around the world in 2003. He’s also studied Hendra virus. It takes its name from the town in Australia where it first emerged in 1994. That outbreak killed 14 racehorses and a horse trainer. At least 10 more outbreaks of Hendra virus have occurred in Australia.

A discovery that bats are the reservoir for this disease would later prove crucial to cracking the mystery behind yet another deadly disease outbreak.

It started in Southeast Asia during the late 1990s. Workers at a massive pig farm in northern Malaysia began noticing troubling symptoms in their animals. Pigs came down with a loud, barking cough and began behaving strangely. They twitched and developed muscle spasms.

The virus spread through saliva when pigs coughed and through mucus from the animals’ dripping noses. Some pigs died. Others recovered after a few weeks or months. Tragically, farm workers also started getting sick. They developed the twitching and spasming seen in the pigs, along with headaches and dizziness. In severe cases, people entered a coma and died.

A huge group of experts, including Epstein, teamed up to probe what caused the outbreak. The group included epidemiologists (scientists who study disease outbreaks), veterinarians, physicians and virus experts from Malaysia, the United States and Australia. These scientists puzzled over why this disease emerged when and where it did — and whether it might show up again. Through intense detective work, they identified the germ responsible. Scientists named the virus Nipah, after the village in Malaysia where it first appeared.

Nipah and Hendra viruses are closely related. In fact, those similarities tipped off the scientists studying Nipah that it, too, might originate in bats. When they looked, these researchers found antibodies to the virus in bats throughout Malaysia.

Antibodies are proteins that are part of the immune system. They attack foreign invaders such as bacteria and viruses. Nipah antibodies would only develop in animals exposed to the virus. Since the bat data showed the virus was widespread in these animals, but hadn’t sickened them, the researchers concluded bats must be reservoirs.

So why had the virus emerged at a pig farm? The bat species harboring Nipah virus normally stays away from people, living in the nearby rainforest. The scientists soon discovered, however, that farmers had planted an orchard of mango trees close to the pigpens. The farm relied on the fruit for additional income. Farm workers also fed the fruit to the pigs.

But the sweet, juicy mangos also attracted swarms of bats. As they dined in the mango trees, bats shed saliva, urine and feces contaminated with the deadly virus into the pigpens below. There the germ found a new host — pigs — and yet another: humans.

From 1998 to 1999, Nipah sickened more than 250 people. More than four out of every 10 of these people died. One million pigs were killed and disposed of to stop the disease’s spread. This cost the farmers huge sums of money. Since then, more than 12 more Nipah outbreaks have struck in Asia, mainly in Bangladesh and India.

Wildlife as pets

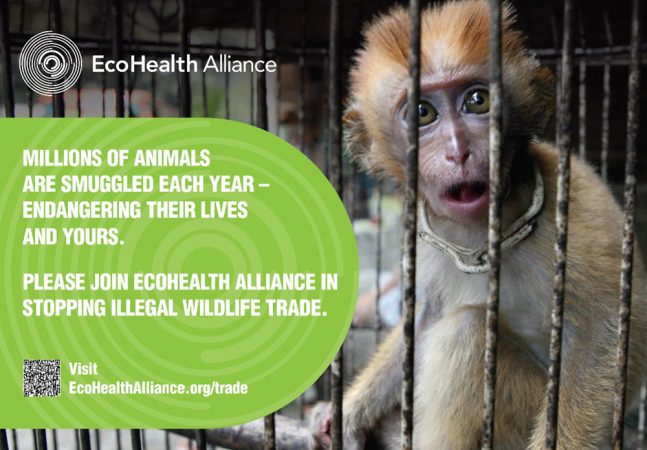

Smith of EcoHealth studies the global trade in wildlife. That is the sale of animals to foreign countries, where they will become pets or food. The United States is the world’s biggest importer of wildlife — both legal and illegal, she says. Between 2000 and 2006 the United States imported 1.5 billion animals and an additional 5,000 metric tons of critters by weight (mostly fish and reptiles). More than 90 percent of the animals were brought in for sale as pets.

Exotic animals can make wonderful pets, says Smith. But that’s only true, she adds, if you make smart, informed choices. EcoHealth Alliance sponsors a website called PetWatch that provides information about the best and worst choices for exotic pets. It bases its recommendations on concerns about human health, the type of care a pet requires (such as frogs that need special ultraviolet light) and the risk that an animal might pose if it got loose in the environment. (Remember those Burmese pythons now reproducing in Florida’s Everglades?)

Turtles, newts, iguanas, frogs and bearded dragons, for instance, are a poor choice for preschoolers, Smith says. Kids that age tend to put their hands and most other things into their mouths. Amphibians and reptiles often carry bacteria, called Salmonella, in their intestines. These germs can taint the outside of the animals too.

Children can become sick when they touch these pets and then put their fingers into their mouths — or worse, put the animal in their mouths. The germs usually cause a mild illness that feels like food poisoning. But Salmonella can kill. It is most deadly to people with weakened immune systems. Each year, this germ sickens about 70,000 people, most of them children, reports Smith.

Wildlife as food

The global wildlife trade also includes exotic species sold as meat. Many cultures consider this a delicacy. Such “bush meat,” as it’s called in Africa, includes rodents, birds, cats, monkeys and reptiles — species that may be threatened, endangered or otherwise protected.

Relatively few animals brought into the United States are destined for dinner tables. Those that are typically come from West and Central Africa. Giant cane rats, for instance, account for about half of the bush meat entering the United States. The remainder includes animals such as chimpanzees and gorillas, deer and bats.

People from societies that have traditionally eaten bush meat drive demand for it in the United States and elsewhere. They often see it as preferable to farm-raised animals because it is unprocessed — and straight from the wild. “I equate it to our organic [food],” says Smith. U.S. residents from West Africa, where the practice of eating bush meat isn’t uncommon, point out that these animals lived on fresh grass. “It’s their perception that bush meat is better and healthier,” Smith says. And some people will pay a lot of money for it, she adds.

But bush meat also has been a source of some of the world’s deadliest pathogens. These include the Ebola virus and the source for human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV (which causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, better known as AIDS). Chimpanzees, monkeys and macaques are reservoirs of various strains of simian immunodeficiency virus, or SIV, which is in the same family as HIV. (HIV actually results from SIV spilling over into people. Since viruses are constantly mutating, the strains found in humans — HIV-1 and HIV-2 — are similar, but not identical to, those found in nonhuman primates.)

Smith works with government officials to intercept bush meat as it enters the United States. It is illegal to bring animal products into the United States unless the meat has first been treated to kill germs. And people cannot legally bring endangered or other animals that are protected into the United States. So smugglers often hide such animals or meat products that they bring across international borders.

When guards at airports or border crossings seize an illegal shipment, Smith and other researchers test samples of it for bacteria and viruses. But much of the illegally imported wildlife, she notes, “is not caught at the borders. So we really don’t have an idea of how much wildlife and their products, such as bush meat, are being imported.”

Just as wildlife germs can infect people, we can spread deadly germs to animals, adds

Melissa Miller. As a veterinary pathologist, she studies animals to determine their cause of illness or death for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife in Santa Cruz. Work by Miller and others now shows that germs can be a type of human pollution. Think of them as biological pollutants, she says, which can harm wildlife.

These living pollutants sometimes come from human or animal feces — poop — that washes into the ocean. (see Explainer: People can sicken animals).

A better way to live with animals

There is no way to completely avoid getting sick. But people can reduce the risk of infections by being smarter about how they interact with animals, says Epstein. One simple tip: Wash hands frequently, especially after handling wild animals.

And the emergence and spread of Nipah virus teaches us the importance of keeping wildlife at a safe distance from livestock.

Respecting wildlife and natural habitats “doesn’t just protect us from the things we know about, like Nipah virus,” says Epstein, “it also will protect us from the things we don’t yet know about.”

Power Words

Word Find (click here to print puzzle)