biology The study of living things. The scientists who study them are known as biologists.

cell The smallest structural and functional unit of an organism. Typically too small to see with the unaided eye, it consists of a watery fluid surrounded by a membrane or wall. Depending on their size, animals are made of anywhere from thousands to trillions of cells. Most organisms, such as yeasts, molds, bacteria and some algae, are composed of only one cell.

colleague Someone who works with another; a co-worker or team member.

debris Scattered fragments, typically of trash or of something that has been destroyed. Space debris, for instance, includes the wreckage of defunct satellites and spacecraft.

digest (noun: digestion) To break down food into simple compounds that the body can absorb and use for growth. Some sewage-treatment plants harness microbes to digest — or degrade — wastes so that the breakdown products can be recycled for use elsewhere in the environment.

generation A group of individuals (in any species) born at about the same time or that are regarded as a single group. Your parents belong to one generation of your family, for example, and your grandparents to another. Similarly, you and everyone within a few years of your age across the planet are referred to as belonging to a particular generation of humans.

immune (adj.) Having to do with the immunity. (v.) Able to ward off a particular infection. Alternatively, this term can be used to mean an organism shows no impacts from exposure to a particular poison or process. More generally, the term may signal that something cannot be hurt by a particular drug, disease or chemical.

immune system The collection of cells and their responses that help the body fight off infections and deal with foreign substances that may provoke allergies.

immunology The field of biomedicine that deals with the immune system. A doctor or scientist who works in that field is known as an immunologist.

laser A device that generates an intense beam of coherent light of a single color. Lasers are used in drilling and cutting, alignment and guidance, in data storage and in surgery.

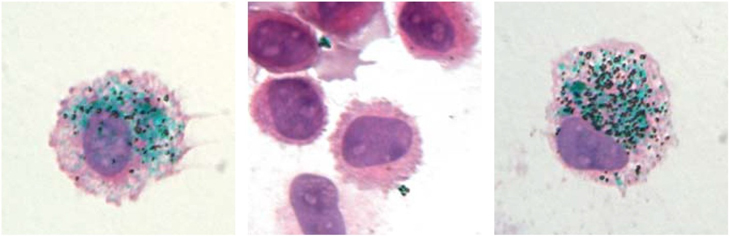

macrophage A type of white blood cell dispatched by the immune system. Like janitors of the body, they gobble up germs, wastes and debris for disposal. These cells also stimulate other immune cells by exposing them to small bits of the invaders.

scavenge To collect something useful from what had been discarded as waste or trash.

skeptical Not easily convinced; having doubts or reservations.