Tiny vest could help sick babies breathe easier

It works by gently pulling on the baby’s belly to draw air into the lungs

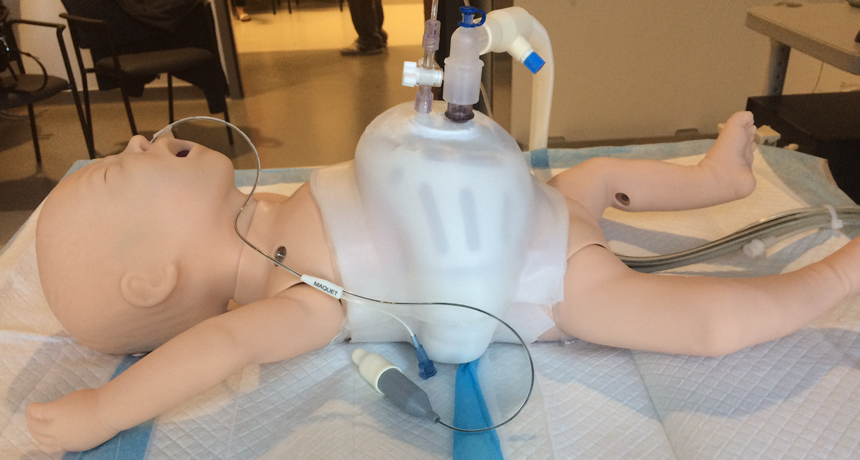

A baby mannequin wears an invention designed to help sick babies breathe. Called NeoVest, it does away with the traditional mask and breathing tubes that get in the way of a baby feeding and bonding with its parents.

St. Michael’s Hospital

Babies that are born sick or prematurely often have lung problems. Many need help just to take a breath. There are machines to help these infants. But using them can come at a cost. “[Their] masks and tubes often leave babies with deformed noses,” notes Doug Campbell. And, he adds, “The wires and machinery mean their mothers can’t hold or breastfeed them.”

Campbell is a pediatrician in charge of an intensive care unit for babies at St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, Canada. He thought there must be a better way to bring life-saving support to these babies. His team has just begun testing one promising alternative.

Called NeoVest, it looks a bit like a tiny lifejacket. Campbell’s team fits the vest around a baby’s belly. The vest is airtight, so when it pulls away from the baby, it creates a vacuum. That, in turn, gently pulls on the belly. This motion draws air into the baby’s lungs.

Elsewhere, such babies would be hooked up to another type of mechanical ventilator. Such machines push air into a baby’s tiny body. The air enters through a tube attached to a mask that is sealed over the nose. These devices continue to breathe for the infants until they are strong enough to do it themselves.

NeoVest avoids the mask and all those tubes and wires that can get in the way of a baby bonding with its mother. In June, the team tested the vest on the first baby. It worked well. Shortly, the researchers plan to start testing the vest on more babies.

Ventilation — a special problem for preemies

Ordinarily, a newborn figures out how to breathe at birth. But in babies born prematurely, the lungs may not be fully developed at birth. Many newborns also develop lung diseases, such as an infection, that impairs their ability to breathe well. To help these children, hospitals often use mechanical ventilators.

These have proven to be life-savers. But they can have side effects. Besides the mask, tubes and wires, a traditional ventilator is unlikely to match the precise rhythm of air intake and exhalations that a baby’s body would normally develop. To compensate, doctors need to sedate babies as a way to help them deal with the severe discomfort of the ventilator being out of sync with their natural breathing rhythms.

NeoVest’s co-creator is Jennifer Beck. She works at St. Michael’s Keenan Research Centre for Biomedical Science. As a physiologist, she studies how the body functions. Her specialty is the science of breathing.

In healthy people, explains Beck, the brain sends a signal to a muscular wall just below the lungs. It’s known as the diaphragm (DY-uh-fram). Signals from the brain tell the diaphragm to contract, bringing in a breath. Other signals tell it when to relax, releasing a breath. When patients are very sick, however, the diaphragm may not respond properly to those brain signals about when to breathe.

Working with her research partner and husband, Christer Sinderby, Beck came up with a solution. A sensor attached to the baby’s feeding tube picks up the brain’s breathing signals. These signals match the NeoVest’s rhythms of expansion and contraction to the baby’s natural breath.

Adults on ventilators may have the same problem with mismatched ventilator breaths. However, the problem is bigger in babies. Why? They breathe faster and tend to have a less regular rhythm. This makes it even harder for a ventilator to match what would be their natural breathing patterns. Beck and Sinderby’s invention solves that problem.

Still a work in progress

The new vest also solves another important problem with traditional forced-breath ventilators, says Michael Dunn. He’s a pediatrician at nearby Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center in Toronto.

“Pushing gas in is not natural and carries a risk of injury to the lungs,” he explains. “Drawing a breath in is more natural,” he says. By encouraging the body to draw air in, he says, “NeoVest has great potential as a way of protecting the lung from injury.”

Still, there are potential drawbacks, he notes. Babies, especially premature ones, have very sensitive skin. The rhythmic pulling on the skin might injure the skin underneath the vest.

That is one of the things Beck will be watching for closely in the St. Michael’s tests. She also will be watching to make sure the vests are properly sealed so they do in fact create a vacuum when they pull away from the baby’s belly.

“We don’t usually think about breathing,” says Beck. “It’s an automatic process. But what happens when you can’t breathe? I want to help the oldest patients down to the tiniest, most vulnerable ones.”

This is one in a series presenting news on technology and innovation, made possible with generous support from the Lemelson Foundation.