No trees were harmed to 3-D print this piece of wood

As it dries, an ‘ink’ made of wood waste twists, curls and folds into complex 3-D shapes

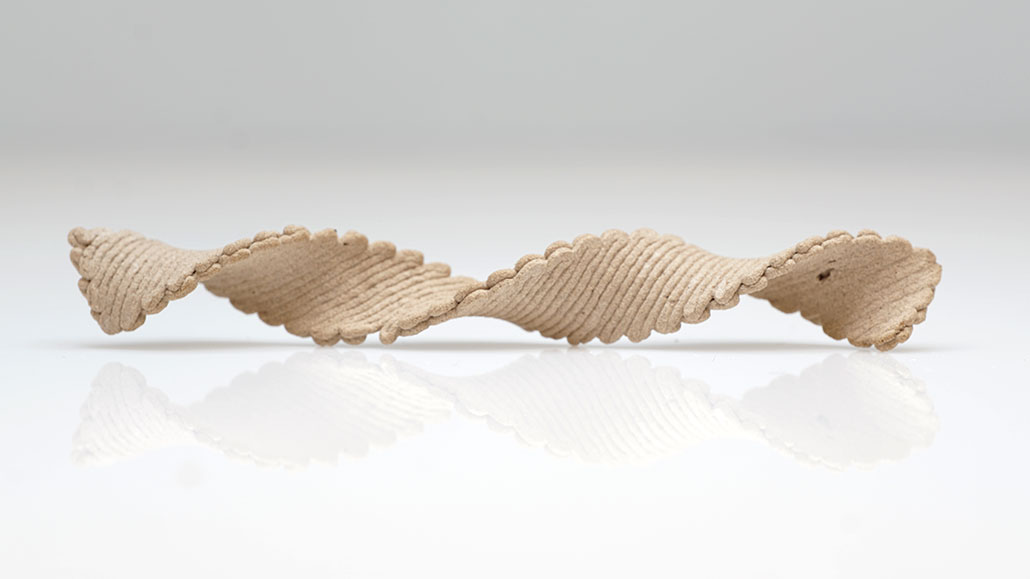

This helix started as a flat strip of 3-D printed wood that curled into its present shape only as it dried. A faster print speed causes the helix to curl tighter than strips printed more slowly.

D. Kam

Scientists have just shown how to 3-D print flat wood so that it later morphs into a desired complex shape. The trick: They relied on what could have been an obstacle — the tendency of damp wood to warp as it dries.

This goes beyond just 3-D printing, says Shlomo Magdassi. He studies nanochemistry at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Israel. His team prints objects that change over time or in response to something. That turns this into four-dimensional — or 4-D — printing.

Plants inspired the work, notes team member Doron Kam, who also works at the Hebrew University. Some seedpods shrink, twist and split open as they dry, spilling their cargo. That twisting action is due to how the pods’ woody fibers line up at the microscopic level. And that, Kam says, “we can mimic.”

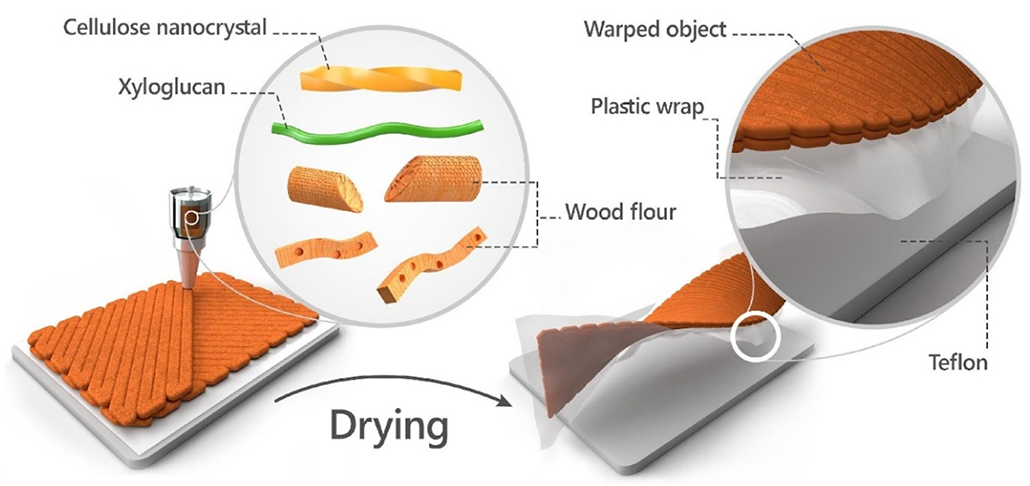

The researchers first had to figure out how to make wood fibers line up in desired ways. To do this, they turned to ground-up wood, known as wood “flour.” They moistened it into a paste to make the ink for their 3-D printer.

The team printed their shapes at different speeds and using different patterns to lay down the ink. After each test, Kam says, “We look to see how it dries.” Along the way, they learned how to 3-D print a self-morphing, seedpod-like structure. They described their technique in the February 2022 issue of Polymers.

They offered even more details about how to control the shapeshifting of wood ink on August 23. They were presenting their work in Chicago, Ill., at the fall meeting of the American Chemical Society.

Whoa, slow down!

Print speed, the team learned, plays a big role. Fast printing causes a flat strip of printed wood ink to curl tighter as it dries. Slower printing leads to looser curls. Why? Quickly laying down the ink makes the woody fibers line up straighter, Kam explains. And that changes how they curve as they dry.

Also critical was the direction an ink was laid down. For example, a flat disk printed with concentric circles will warp differently from a disk printed from straight lines. Taken together, such factors allow engineers to program the shape of the dried object.

“It’s nice to see that they looked also into the effect of gravity in the overall shape change,” says André Studart. If you want to print large structures, he says, that’s important. He’s a materials scientist at ETH Zurich in Switzerland. Studart also likes that the ink comes from “wood waste” — not lumber. That means no trees were logged for these products.

Athanasia Amanda Septevani also likes that. This materials scientist notes there are lots of wastes that might find new uses this way. Consider the palm-oil industry. Septevani works in India at the National Research and Innovation Agency in Indore, Madhya Pradesh. The fruit of palm trees in Indonesia, where she grew up, are crushed to make oil. Each ton of palm oil creates about one ton of plant wastes (in the form of empty palm fruits and crushed kernels). “The waste is massive,” she says. But the new study points to the value in finding use for such wastes.

The new ink is made from wood flour and “a kind of glue,” Magdassi says. Even the glue comes from wood wastes. These are nanocrystals — “very tiny, needle-shapes of cellulose,” Septevani explains. Cellulose, she points out, also makes up about 40 percent of palm-oil wastes.

Cellulose nanocrystals in the ink “allow us to use less water,” says Kam. That provides better control over the shape that printed wood will take as it dries.

Still a work in progress

Kam hopes this technology could change the way people build things. Most manufacturers try to make things — “like a brick” — that last as long as possible, he says. But that’s not how nature works. Organisms grow, die and rot. This allows their building blocks to be reused to make new organisms.

His team’s materials also are reusable. Says Kam, you can “take any old wood.” Perhaps an old chair or bedroom dresser. Rather than trash it, grind up its wood and reuse the sawdust — flour — to make something new.

Kam hopes that one day, we won’t carve up our trees to make new chairs but instead just 3-D print a new one. “You sit on it for three or four years,” he says. When you tire of it, just grind it up and print something new.

This is one in a series presenting news on technology and innovation, made possible with generous support from the Lemelson Foundation.