Copper ‘foam’ could be used as filters for COVID-19 masks

The lightweight new material is washable and recyclable

Face masks have become a common method of protection during the COVID-19 pandemic. A new copper “foam” could make those masks work even better.

Pollyana Ventura/E+/Getty Images

By Sid Perkins

Face masks have become a vital tool in slowing the spread of the virus that causes COVID-19. They help filter or block spit or mucus droplets that carry infectious particles. Even homemade fabric masks can do a good job. But many are not very durable. Now, researchers have come up with a new sort of filter for use in masks. Made of copper, it’s sturdy and lightweight. The sponge-like material also is easy to clean and can be recycled. In tests, it performed as well in filtering as a standard N95 mask. It might even trap and kill bacteria, its developers say.

Masks to guard against viruses can be made of many different materials. Some fabric ones even use extra layers — often cotton, silk or some synthetic — to boost their filtering prowess. Others use paper similar to coffee filters. With so many people now being asked to wear masks during the pandemic, researchers began scrambling to identify new and better filters. Kai Liu was among them.

This materials scientist thought his team at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., had a head start. They already had been testing materials to filter small particles out of polluted air.

Recalls Liu, “We saw that small droplets carrying viruses were the same size as some atmospheric pollutants.” Right away, he says, “we thought we should check our materials to see if they might make good filters for face masks.”

Liu’s team soon began cranking out new batches of a material they call copper foam.

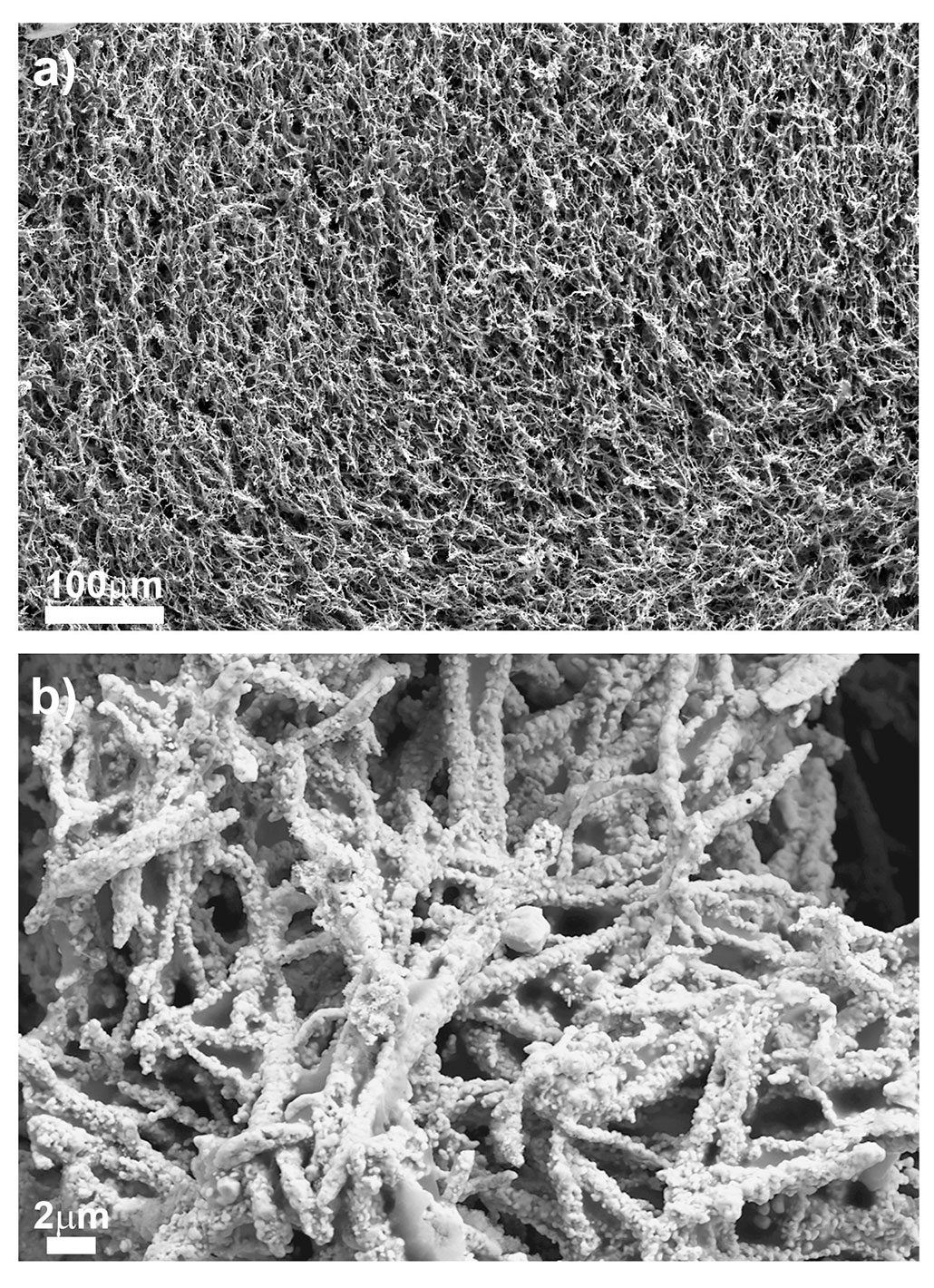

They started with templates to make copper nanowires. The diameter of each wire was typically about 200 nanometers, says Liu — or less than one ten-millionth of an inch. After dumping those wires into ultrapure water, they flash-froze the mix in liquid nitrogen. Afterward, they put the copper-filled ice in a vacuum chamber. It drove off the ice to freeze dry the now loosely packed mass of tiny copper wires. Finally, they heated the mass of wires to 300° Celsius (572° Fahrenheit). This fostered chemical reactions that helped bind them into a mesh.

Unfortunately, that mesh was super flimsy, says Liu. Tests showed it would collapse if someone breathed on it. Obviously, that would not work well in masks. So, the researchers kept tweaking the process.

They bathed the weak mesh in a liquid that included copper ions. Then they sent an electric current through this chemical bath. That deposited more copper onto the nanowires, thickening them. Liu says it also helped weld the wires at points where they touched. In tests, some samples of this material could now support about 10,000 times their own weight without collapsing. That was true even when the material was 85 percent air.

More importantly, this 85-percent-air foam filtered out tiny particles. A sample 2.5 millimeters (0.1 inch) thick captured 97 percent of particles between 0.1 to 0.4 micrometers in diameter. Such super-small particles not only are the hardest to trap but also the size of the smallest aerosol droplets that can carry virus particles. These particles don’t just get trapped by the material’s tiny pores, Liu explains. The particles are particularly attracted to the enormous surface area that the nanowires provide. They get stuck on the mesh as they try to move through that wire maze between the outer and inner edges of the filter. Liu and his colleagues described their innovative new foam April 14 in Nano Letters.

Another approach

The Georgetown team developed “an interesting and innovative way to produce their material,” says Semali Perera. She’s a chemical engineer at the University of Bath in England. She wonders, however, if it would be hard to scale up the process to make really big batches and large pieces of the thin foam for use in masks.

Perera’s team is taking a different approach to germ filters. Theirs were initially targeted to collect and kill bacteria. Now they’re being designed to trap viruses, too.

One promising material her team is exploring is a plastic-like foam made out of a polymer called polyimide. To give it a germ-killing punch, the researchers added copper and nickel. Nickel helps slow the growth of bacteria, and copper helps kill them. Those metals make up about 80 percent of the material, says Perera. The plastic-like polymer helps bind the metal atoms together.

Instead of using a multi-step process to make its material, this group mixes its ingredients in one container all at once. A chemical reaction that generates large amounts of carbon dioxide makes the material frothy, Perera notes. As it foams, it expands into a mold. Within three seconds it hardens into its final shape. To make big batches, the researchers merely mix more of the ingredients and then cook them up in a bigger pot.

Perera and her team are working with companies to design new products. One potential use for their material might be filters for home air-conditioners.

UPDATE: In June, Dr. Liu’s team’s innovation was judged one of the top 10 entries in Phase I of a government-sponsored competition to design low-cost, easy-to-use masks. If they also are judged one of five winners in Phase II of the challenge, they’ll earn a share of $400,000. More info on the competition can be found at https://drive.hhs.gov/mask_challenge.html.

This is one in a series presenting news on technology and innovation, made possible with generous support from the Lemelson Foundation.