Headphones or earmuffs could replace needles in some disease testing

Sensors hooked up to those muffs would ‘sniff’ for telltale gases escaping through the ears

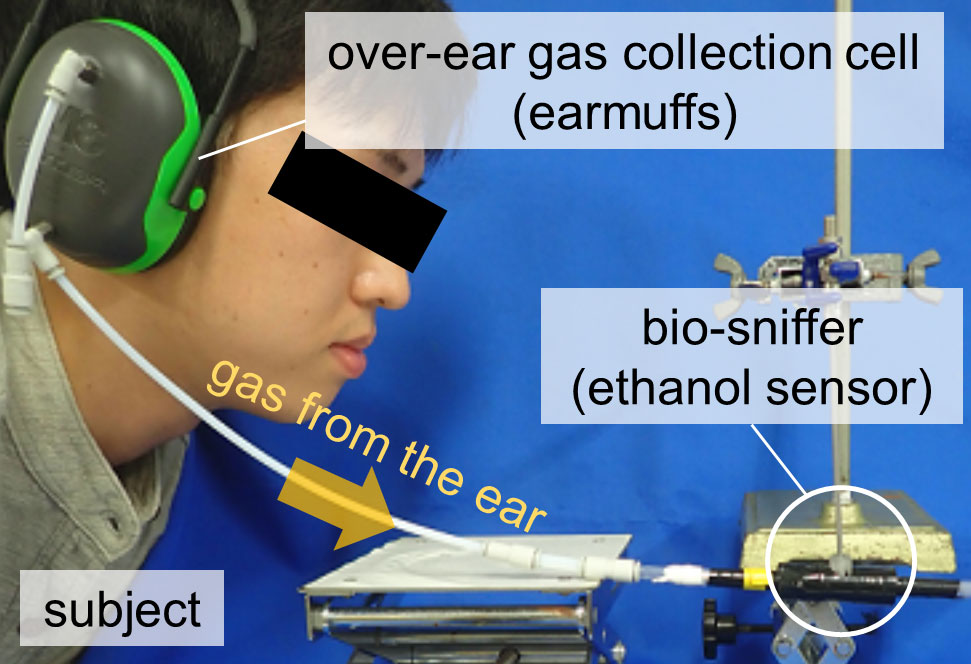

Earmuffs or headphones (like those shown above) could soon become part of a system that collects gases to help diagnose disease.

Strauss/Curtis / Getty Images

By Sid Perkins

The body gives off many gases. Some stink. Many have no odor. Although some scents may even signal a need to bathe, other gases might point to serious disease. Now, researchers have come up with a system that uses earmuffs to capture and sniff out that last group of gases.

Doctors could get the information as patients wear a set of headphones. Results could be ready within minutes, scientists say. Best of all: No needles!

“The ear is a good place to monitor,” agrees Moamen Elmassry. He’s a microbiologist at Princeton University in New Jersey. He did not take part in the project. The ear’s skin is fairly thin, he notes. So gases don’t have to travel far to get out of the blood and escape through skin pores.

In new tests, a team in Japan found that they could measure changes in the amount of alcohol emitted from the skin of a volunteer’s ear. It could work much like a Breathalyzer that police use to test people for driving drunk. But the developers hope their new system will find most of its use elsewhere. With the right sensor, they say, their system could scout out disease. They shared details of the device June 10 in Scientific Reports.

Why it works

Tiny amounts of the gases dissolved in the blood leave the body every time you exhale, says Koji Toma. He’s a biomedical engineer at the Tokyo Medical and Dental University in Japan. For instance, high levels of acetone (ASS-eh-tohn) in the breath can signal diabetes or liver disease.

Such blood gases also can escape through pores of your skin, Toma adds. In previous tests, his team covered people’s hands with plastic bags to collect these gases. But gases coming from the skin’s sweat glands sometimes confused the sensors. Indeed, the palm has a whopping 620 per square centimeter (0.15 square inch).

So his team turned to the ears. Even they have 140 sweat glands per square centimeter.

To collect the gases, they selected earmuffs that make a tight seal with the head. These are the type people often wear to shield the ears from loud noise. His group drilled two holes in the muff covering one ear. A tube slowly pumped air in one hole. Another tube pulled air out of the second hole and sent it to a sensor.

For their first tests, the researchers recruited three men. Each had to avoid drinking alcohol for at least three days before taking part. Once in the lab, these men donned the earmuffs and sat for 10 minutes as the system recorded normal gas levels leaving their ears. Afterward, the men guzzled a big dose of alcohol. Over about 5 minutes, each downed about as much as is found in three 12-ounce (350 milliliter) cans of beer.

About 7 minutes later, the earmuff system sniffed out a rise in alcohol leaving the skin. (That’s how long it took for the alcohol to be digested, enter the blood and then work its way out through the skin pores.) Roughly 50 minutes after that, alcohol levels peaked at about 183 parts per billion in air. Levels continued falling after that until the 90-minute test was over. While the test of this prototype took an hour and a half, Toma suspects one used by a doctor’s office would take far less time.

To measure other gases, Toma says, his team only needs to change out the sensor. Doctors would choose a sniffer designed to detect a particular vapor. The team might also replace the earmuffs with a one-eared version to make it a bit more comfortable.

Elmassry imagines yet another possible benefit. The new system could help doctors tell whether a child’s ear infections had been caused by bacteria or a virus. How? Each type of infection exudes different gases. That, in turn, could guide how doctors treat the disease. Most bacterial infections respond to antibiotics, while viral infections never do.

This is one in a series presenting news on technology and innovation, made possible with generous support from the Lemelson Foundation.