An inspiring home for apes

A group of scientists wants to establish preserves where orangutans and other primates have the chance to learn and create.

By Emily Sohn

It would be hard to live in a cage. You’d have to stare at the same old scenery every day. You couldn’t walk to the store, go to the movies, or decide what to eat. After a while, you could end up losing your enthusiasm for life.

Chimpanzees, orangutans, and other primates might feel the same way, says Lyn Miles. She’s an anthropologist at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. “Apes are bored to death in most facilities,” she says. “They pace. They develop nervous habits. They get depressed.”

Miles is a member of a vocal group of scientists and activists who say that captive apes deserve a richer life than they get in most zoos and primate centers. As president of a foundation called Animal Nation (formerly ApeNet), Miles is working with celebrities and others to create special preserves for primates. She described her project at a recent meeting of the American Primatological Society in Madison, Wis.

|

|

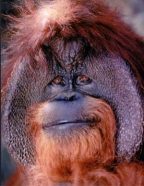

A portrait of the orangutan known as Chantek, now a resident of Zoo Atlanta.

|

| Chantek Foundation |

Instead of just giving monkeys a phone book to rip up every once in a while to keep them amused, Miles envisions a place where apes have the freedom to decide what they want for breakfast and whether to play tic-tac-toe or make music.

Featuring tool making, music, and arts and crafts, “it would be a place where the entire lifestyle is based on developing the intellectual capacity of these animals,” Miles says.

Raising Chantek

Miles’ beliefs about primate intelligence come from nearly 27 years of experience with an orangutan named Chantek. From 1978, when he was 9 months old, until 1986, Chantek lived with Miles in a trailer on campus. She raised him as she would a human child.

To communicate with her foster primate, Miles taught Chantek sign language. He learned to tell her what he wanted for breakfast. He cupped his hands together to say he wanted more. His vocabulary grew to more than 150 words.

|

|

Lyn Miles shows a necklace made by Chantek.

|

| Emily Sohn |

From the beginning, Chantek was also responsible for doing chores. He had to clean his bedroom to get his allowance. He helped cook spaghetti for dinner.

Over time, Miles and Chantek grew closer. In many ways, she says, he started to act more and more like a real kid. She took him to fast food restaurants, lakes, and playgrounds. They would go to a nearby mountain to watch hang gliders soaring in the air. They even celebrated holidays together.

To describe Christmas, Chantek used signs to say “Red Hat Day.” His name for Miles was “Mother Lyn.”

Tool time

At some point, Miles noticed that Chantek was fascinated by tools. So she gave Chantek supplies and encouraged him to explore. She figured anything was possible.

In the wild, orangutans constantly have to solve problems, Miles says. For example, they have to figure out how to get ants out of a log. In captivity, it might make sense for them to apply these problem-solving skills to artistic pursuits.

After using signs to ask Miles about her jewelry, Chantek strung beads onto a string and gave it to her. She felt an overwhelming sense of pride. “He said it was a necklace,” she says. “I just cried.”

In 1986, after Chantek had grown too large for his quarters in Chattanooga, he was moved to the Yerkes Regional Primate Research Center at Emory University in Atlanta.

Today, Chantek is 27 years old, and he has lived at Zoo Atlanta since 1997. Miles visits him often. He still makes jewelry, using his mouth and hands to string the beads and to tie special knots that make the necklaces adjustable. He also creates what Miles describes as “found art assemblages” out of interesting objects that he finds lying around.

To top it off, Chantek participates in a band called Animal Nation, which was formed by Miles. The band has five human members, who play a variety of traditional instruments from around the world, often in unusual ways. Their music uses lots of percussion and has a strong beat.

|

|

Human members of the Animal Nation band wearing their animal masks.

|

| Animal Nation |

Chantek helps compose the music, Miles says. “He plays notes on the keyboard, and we write songs around his efforts,” she says. “He also keeps the beat.”

The people in the band wear animal masks when they perform. Chantek doesn’t have to dress up.

Ape communication

Miles uses the term “enculturation” to describe Chantek’s integration into human society. She says he’s the only enculturated orangutan in the world.

Other anthropologists have cultivated similar capabilities in gorillas and chimpanzees. In captivity, some of these primates have also learned sign language. Others can count and do simple math.

Even in the wild, researchers have been awed by humanlike gestures in nonhuman primates. Anthropologist Jane Goodall, for one, still marvels at the time a chimpanzee reached out and gently tapped her arm. Goodall spent many years getting to know chimpanzees at Gombe National Park in Tanzania.

Some experts disagree with the idea of “humanizing” apes. Because many types of primates look a bit like us, it’s tempting to see pieces of ourselves in them, they say. This resemblance, however, doesn’t mean that our interpretations of the animals’ behaviors and needs are correct. And it isn’t necessarily fair to assume that what makes us happy makes apes happy, too.

|

|

One of many necklaces made by Chantek.

|

| Emily Sohn |

Miles argues that human-primate interactions might open a window into another universe, right here on Earth. There are people looking for signs of intelligent life in outer space, she says. Why not make contact with intelligence here at home first?

“When I was a girl,” Miles says, “I used to look out the window and wonder what was out there. Now, I make contact with nonhuman intelligence every day.”

The more we communicate with primates, she adds, the more we might learn about them and about our own origins.

Miles remembers one rainy day when Chantek grabbed a big leaf to use as an umbrella. Then, he ripped it, gave half to her, and signed that she should put it on her head. “I felt like he was reaching across millions of years,” she notes, “saying, ‘I care about you. I don’t want you to get wet either.'”

Future sanctuary

Rock star Peter Gabriel started the foundation called Animal Nation in 2002. One of the foundation’s goals is to create a culture-based preserve for apes in Hawaii on the island of Maui.

This sanctuary would house all four types of great apes—orangutans, chimpanzees, gorillas, and bonobos. The apes would have lots of land across which to roam and lots of intellectual stimulation, including puzzles to play with and materials for art projects. The facilities would be open to the public, and people could interact with resident animals over the Internet.

If all goes well, the center could open in a couple years. So far, Animal Nation has raised more than $10 million toward this goal, Miles says. The organization is also trying to obtain funds for a second sanctuary in the Atlanta area for Chantek.

Recognizing primate intelligence could help motivate people to protect the animals and their habitats, says Shelly Williams. She’s a primatologist at Georgia State University in Atlanta.

Mystery ape

And there’s still a lot to learn about primates, including the possibility of discovering new species of apes. “In this day and age, to find a new type of ape would be astounding,” Williams says.

Nonetheless, Williams has come across evidence of what might be such an animal. In two expeditions to an isolated area in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in Africa, Williams has encountered groups of large apes that look and behave like neither chimpanzees nor gorillas nor bonobos but seem to combine some features of all three.

For example, unlike chimpanzees, which typically nest in trees, some of these apes build large ground nests in or near water.

Some individuals appear to be larger than gorillas. Williams brought a mold of one of the newly found creature’s footprints to the primate meeting in Madison. The footprint was enormous—larger than that of the average gorilla.

|

|

Shelly Williams with a mold of the footprint of a newly found giant primate.

|

| Emily Sohn |

It isn’t clear yet whether these apes belong to a new species or are somehow directly related to known primates. Observations suggest that there may even be as many as four distinct types of apes in this isolated region of Africa.

Who knows what remains to be discovered—whether you’re communicating with apes in preserves or observing primates in the wild?