These jellyfish can learn without brains

Studying the ability to learn in animals so different from us could help reveal how learning evolved

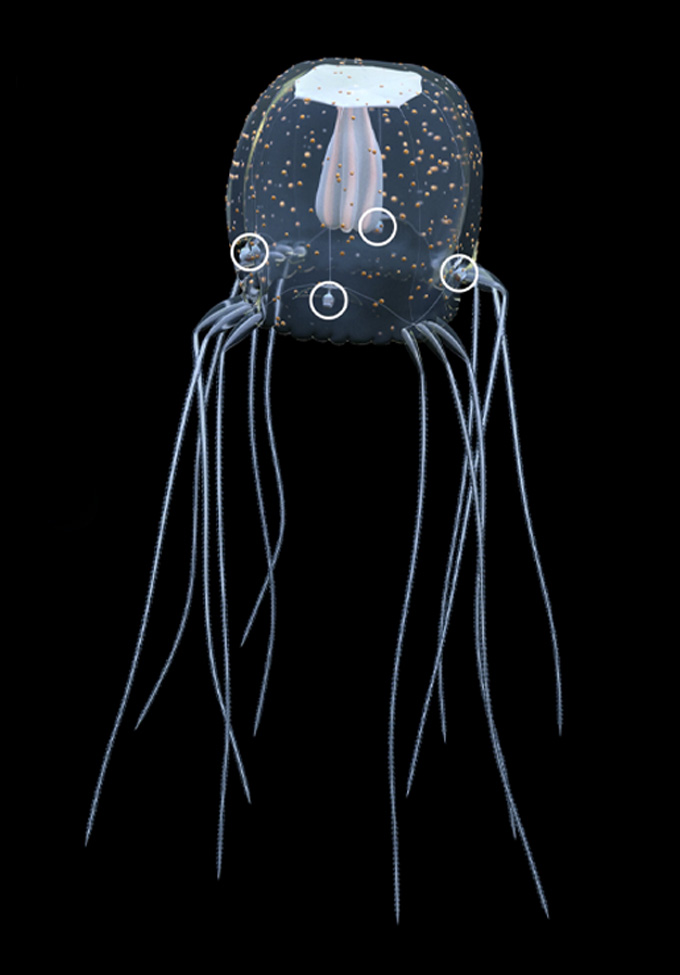

Fingernail-sized Caribbean box jellyfish use their 24 eyes to spot and dodge mangrove roots.

J. Bielecki

For Caribbean box jellyfish, learning is literally a no-brainer.

Despite lacking a central brain, these animals learned to spot and avoid obstacles in a new study. This is the first evidence that jellyfish can do something called associative learning. That’s the ability to make mental connections between events — such as seeing something and running into it — and then changing one’s behavior accordingly.

“Maybe learning does not need a very complex nervous system,” says Jan Bielecki. Maybe any creature with even a simple nervous system can learn. If so, this new insight might help point to how learning evolved in animals.

Bielecki studies animal nervous systems at Kiel University in Germany. He and his colleagues shared their new findings September 22 in Current Biology.

Dodging obstacles

The nervous systems of Caribbean box jellyfish (Tripedalia cystophora) are fairly simple. They include four “rhopalia” that dangle off a jellyfish’s body. Each rhopalium has six “eyes.” It also has about 1,000 neurons to process what those eyes see.

Box jellyfish use their vision to navigate the tropical lagoons in which they live. To hunt the tiny crustaceans they eat, these jellyfish must steer between the roots of mangrove trees.

But weaving between those roots is not simple. Caribbean box jellyfish judge a root’s distance based on how dark it looks compared to the water. In other words, the jellyfish look at a root’s contrast. In clear waters, nearby roots have high contrast. Only distant roots fade into the background. But in murky waters, even nearby roots can blend into their surroundings and have low contrast.

Waters can become murky fast due to tides, algae and other factors. So the researchers wondered if Caribbean box jellyfish could learn that low-contrast objects — which might at first seem distant — were actually close by.

Water tank tests

To find out, the team put 12 jellyfish into a round water tank. The tank was surrounded by low-contrast gray and white stripes. Such stripes might appear to a jellyfish like distant mangrove roots in clear water.

A camera filmed the animals for about seven minutes. At first, the animals seemed to see the gray stripes as distant roots and swam into the tank wall. But those collisions seemed to lead the jellyfish to reconsider the stripes. Soon, the creatures treated the gray stripes more like close roots in murky water — and avoided them.

The jellies’ average distance from the wall was about 2.5 centimeters (1 inch) in the first couple of minutes in the tank. By the final few minutes, they were an average 3.6 centimeters (1.4 inch) from the wall. The jellyfish also stopped bumping into the wall quite so much. Their average rate dropped from 1.8 bumps per minute to 0.78 per minute.

“I found that really amazing,” says Nagayasu Nakanishi. “I never thought that jellyfish could really learn.” This biologist is based at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. He has studied jellyfish nervous systems before. But he didn’t take part in the new work.

Björn Brembs views the results more cautiously. He studies the nervous systems of animals at the University of Regensburg in Germany. Brembs points to the small number of jellyfish tested. “I want this to be true, as it would be so very cool,” he says of the results. But it will take tests with more jellyfish to convince him that the animals really do learn.

Jellyfish learning centers

In other tests, the researchers snipped rhopalia off jellyfish. They placed those eye-bearing nerve bundles in front of a screen. That screen showed low-contrast, light gray bars. Meanwhile, an electrode gave the rhopalia a weak electrical pulse. This mimicked the nerve signal a rhopalium would get if a jellyfish bumped into something.

At first, the rhopalia ignored low-contrast bars, as if they were distant roots. But receiving “bump” signals when they saw those bars made them start paying attention. Their nerves started sending out the types of signals they emit when a jellyfish darts away from something.

This suggests that the rhopalia alone can learn that seemingly distant, low-contrast objects are in fact close enough to avoid. That, in turn, hints that these nerve centers are behind Caribbean box jellyfish learning.

“That’s the coolest part of the paper,” says Ken Cheng. “That gets us one step down into the … wiring of how it works.” Cheng is a biologist at Macquarie University. That’s in Sydney, Australia.

For Gaëlle Botton-Amiot, tracing learning to the rhopalia raises new questions. “They have four of these things in their bodies. So how does that work?” asks this neurobiologist. If a jellyfish loses one of its rhopalia, does it forget everything those eyes saw and the neurons had learned? Or do the other rhopalia remember it?

Evolution of learning

Botton-Amiot has studied sea anemones at University of Fribourg in Switzerland. Her work hints that like jellyfish, those sea creatures can learn.

Sea anemones and jellyfish both belong to a group of animals called cnidarians. “Showing that cnidarians that are so different [can both learn],” she says, “means that it’s probably super widespread within them.” Perhaps jellyfish and sea anemones both inherited that ability from a common ancestor.

It’s also possible that the ability to learn arose in different animals independently, Nakanishi says. Finding out just how nerve cells in jellyfish or sea anemones accomplish learning could shed light on this. For instance, Nakanishi says, scientists could look at what chemicals play a role in how different animals learn.

“If there’s a lot of similarities in the mechanism of how they learn, then that would be suggestive of common ancestry,” he says. “But if they evolved independently, then you would perhaps expect very different mechanisms of learning.”