Jumping ‘snake worms’ are invading U.S. forests

As they eat protective ground cover, they’re harming soils and ecosystems

Brad Herrick of the Madison Arboretum holds a handful of invasive Asian jumping worms. Two of the three invasive jumping-worm species spreading across the United States have been found in Wisconsin.

UW–Madison Arboretum

By Megan Sever

Add “snake worms” to the list of things Americans can worry about this year.

These jumping earthworms, which came from Asia, are known for their wild thrashing behavior. Now they are eating their way across the United States. Along the way, they are displacing other earthworms, centipedes, salamanders and ground-nesting birds. This alters forest food chains. And the jumpers are spreading fast. They can invade an area the size of 10 U.S. football fields in a single year! Now research shows they also damage the forest soils they inhabit.

Three species of these invaders are wriggling across the United States. They first arrived more than 100 years ago, probably in pots of imported plants. But in just the past 15 years, they’ve begun to spread especially widely. Now, they are well established across the South and Mid-Atlantic states. Some have reached parts of the Northeast, Upper Midwest and West too.

Scientists don’t know exactly why the worms have started to spread so quickly. They think climate change may be playing a role. Warmer winters in the North mean the worms can spread to new areas that used to be too cold.

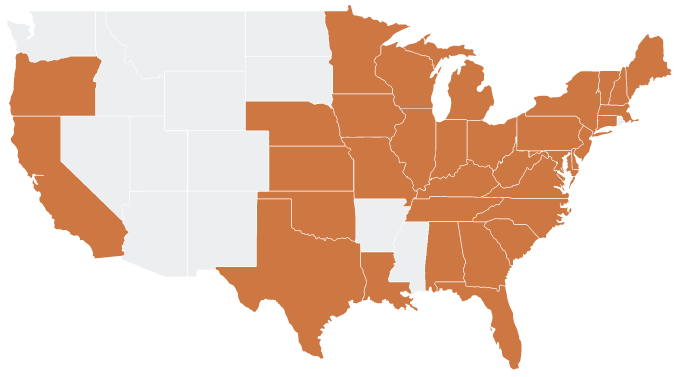

States known to have jumping worms

In the past few years, scientists have determined that three species of Asian jumping worms can be found in at least 34 states, possibly more. These worms are now well established across the South and Mid-Atlantic and have reached states in the Northeast, Upper Midwest and West.

Sources: CABI.org/isc, Chih-Han Chang Soil Ecology & Biodiversity Lab; state departments of natural resources and invasive species councils; B. Herrick/UW–Madison Arboretum, Bruce Snyder/Georgia College

But humans are aiding the worms’ spread, too, says Nick Henshue. He studies worms and soil ecology at the University at Buffalo in New York. The new invaders are often called Asian jumping worms, crazy worms, snake worms or Alabama jumpers. Their scientific names are harder to remember: Amynthas agrestis, A. tokioensis and Metaphire hilgendorfi.

People have been buying some as fishing bait. Anglers like these worms because they wriggle and thrash like angry snakes. That lures fish, explains Henshue. Some people also buy them as worms for compost piles because they gobble up food scraps far faster than other earthworms — too fast, in fact.

But these invaders pose a problem when it comes to ecology. For example, their eggs are held in cocoons small enough to easily catch a ride on a hiker’s or gardener’s shoe. They also can be moved with mulch, compost or plants. Hundreds can exist within an area no bigger than the top of your school desk.

Jumping worms grow faster and reproduce more quickly than other earthworms, such as nightcrawlers. Plus, jumping worms don’t need mates to reproduce. That means one worm can jumpstart a whole invasion.

Another concern: These animals consume more nutrients than other earthworms. They turn soil into tiny pellets that resemble coffee grounds or ground beef. Henshue says it becomes like “taco meat.” This pellet-like soil can make it hard for native plants and tree seedlings to grow. It also makes the soil far more likely to run off in a rainstorm.

Denuding forest soils and altering their microbes

Scientists worry most about the worms’ effects on “leaf litter.” This is a layer of decomposing leaves, bark and sticks. It can cover forest floors deeper than the height of a soda can. When the worms invade, they chomp up that leaf litter. What’s left is bare soil whose structure and mineral content has changed, notes Sam Chan. He studies invasive species with Oregon Sea Grant at Oregon State University in Corvallis. These worms can reduce a forest’s leaf litter by 95 percent in a single season, he’s found.

Reducing leaf litter means less protection for the creatures that live on the forest floor. It also means fewer nutrients and less protection for young trees. Where the ground is bare, seedlings cannot grow. That means forests cannot rebuild themselves. Instead, different plants move in — usually invasive ones, says Bradley Herrick. He is an ecologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison Arboretum. The new invasive species crowd out native ones.

What you can do

Scientists have not yet found any “silver bullet” to get rid of the worms, says Bradley Herrick. So the best bet, he says, is prevention: Don’t bring them into your area in the first place. That means:

- clean your shoes off before and after hiking so you don’t move their eggs

- only use, sell, purchase and plant landscape and gardening materials that are assured to be free of worm eggs (usually because they’ve been heat treated)

- don’t share plants and landscape materials

- don’t buy Asian worms for bait. And don’t ever dump your bait into the water once you’re done with it.

If you get infested, there’s little you can do. If you can catch the worms, put them in a plastic bag and throw them away. You can draw more worms to the surface using a mustard and water solution. In fact, that’s an awfully fun science experiment!

New research shows these worms also are changing the chemistry of soils and the microbes in them.

Herrick and other scientists sampled soils in which the jumping worms lived. After the worms invaded, there was more nitrogen and less carbon, they found. That can affect which plants will grow there, Herrick says. Nitrogen is a necessary nutrient for plants. But when there’s too much or it’s available at the wrong time of year, it can be toxic or unusable.

The scientists also studied the release of carbon dioxide from soils. Microbes and animals living in the soil emit this greenhouse gas. And the longer the worms had lived in the soils, the more carbon dioxide those soils shed into the air, reports Gabriel Price-Christenson. He is a soil scientist. He works at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign where he led the new study. His team described its findings in the October issue of Soil Biology and Biochemistry.

That team also collected DNA from worm poop and guts. This DNA let them study the microbes in each species of jumping worm. Then they tested the soils for changes in the bacteria and fungi in them. Each species of jumping worm housed different microbes in its gut, these data show. That’s “a really important find,” says Herrick. Until now, he says, scientists had thought all jumping worms were very similar.

So, each worm species might have a unique position, or niche (Neesh), in the environment. This allows multiple species to thrive as a group, Herrick says. The finding also makes sense, he adds, as scientists have found multiple species living together. But it’s still a surprise that such similar worms would host very different bacteria.

If the worms have different niches, they likely also will have different effects on other soil dwellers. These include other worms, fungi and bacteria. Plus, Herrick suspects, the different jumpers probably have different effects on their soil’s chemistry.

The newfound worm changes to soils are important, Henshue says. But there’s still a lot of unknowns. For instance, how much farther might the worms spread? And how many different types of environments might they invade? Another important question: How do weather conditions affect the worms? A long drought this year in Wisconsin seems to have killed off many of the worms in the arboretum, Herrick says.

He says that as a sign that maybe even these hardy invaders have their limits.

How to tell jumping worms from regular earthworms

Earthworms all look alike, right? Well no. From their bodies to how they move to their poop, here’s how to tell the difference between invasive jumping worms and a common species, European nightcrawlers, at a glance.

Jumping worms

(Amnythas spp.)

Color: Smooth, glossy dark gray to brown

Length: 10–13 centimeters (4 to 5 inches)

Clitellum (or ring): White and encircles whole body

Movement: Serpentine thrashing

Castings: Granular soil, looks like coffee grounds

European nightcrawlers

(Lumbricus sp.)

Color: Slimy pinkish or nude

Length: 15–20 centimeters (6 to 8 in.)

Clitellum (or ring): Pink and partially encircles body

Movement: Slowly wriggle and stretch

Castings: Neat piles in normal-looking soil