Jupiter has a never-before-seen jet stream — and it’s speedy

This high-altitude current may help untangle what’s happening above planets’ equators

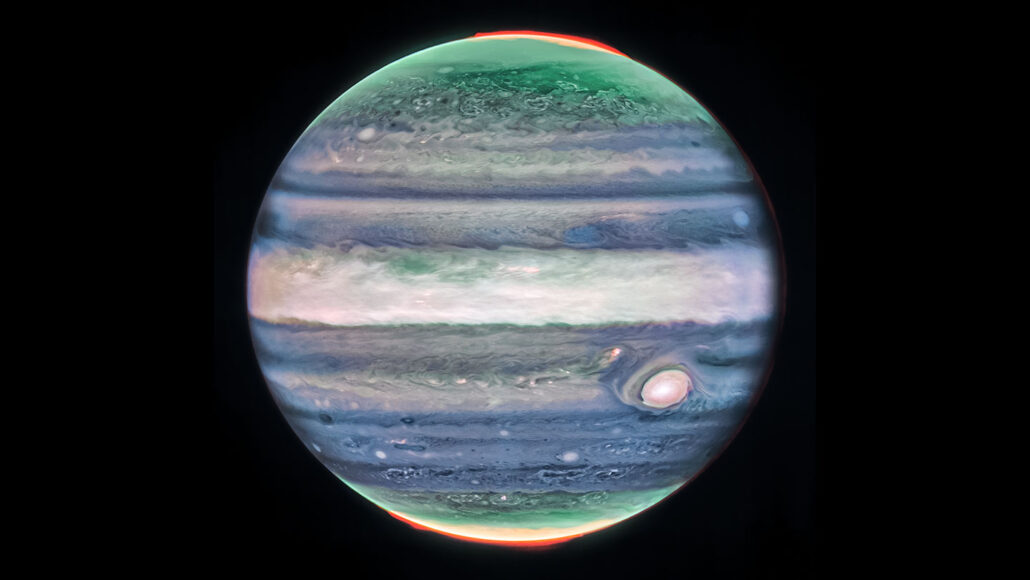

This false-color image reveals new details of Jupiter’s atmosphere. A thick band of clouds circles the equator. Some of the bright white spots in this area are storms. Auroras, in red, can be seen over the poles. This image comes from the James Webb Space Telescope.

NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, R. Hueso/Univ. of the Basque Country, I. de Pater/UCB, T. Fouchet/Observatory of Paris, L. Fletcher/Univ. of Leicester, M. Wong/UCB, J. DePasquale/STScI

New beauty shots of Jupiter reveal a speedy jet stream looping above its equator. It’s located at a level of the atmosphere never imaged before.

Researchers have known Jupiter had jet streams since 1979, when NASA’s Voyager spacecraft flew by. Those jet streams are relatively stable winds. They occur near the planet’s main cloud decks, in a part of the atmosphere known as the troposphere. The newly spotted feature lies 20 to 40 kilometers (12.4 to 24.8 miles) higher up. That’s in the gas giant’s stratosphere.

Scientists noticed it in images from the James Webb Space Telescope, or JWST. The speedy current flies at about 500 kilometers (311 miles) per hour. That’s roughly twice as fast as the jet streams below.

“We were not expecting to find these strange motions in the equatorial atmosphere,” says Ricardo Hueso. An astrophysicist, he works at the University of the Basque Country in Bilbao, Spain. None of the theories about the planet’s atmosphere predict a change in winds at this altitude, he says.

It’s not clear yet what causes the speedy jet.

“If you have very intense motions, you need energy to produce those motions,” Hueso says. This energy could come from storms below the jet. The wind may also be linked to happenings higher in the atmosphere. Above the jet, there’s a spot where scientists have noticed that temperature and wind speeds rise and fall over periods of about four years. Similar cycles over the equator also occur on Saturn and Earth.

Earlier views of Jupiter couldn’t image this part of the stratosphere. Its altitude lies below what telescopes on Earth glimpse. And it’s above what the Hubble Space Telescope captures. However, by using special filters, JWST was able to peek into this mysterious region. These filters select regions of infrared light that are not visible to human eyes.

Hueso’s group reported its new discovery October 19 in Nature Astronomy.

Thibault Cavalié is a planetary scientist at the Bordeaux Astrophysics Laboratory in France who did not take part in the new work. The new study turned up “this missing piece of the puzzle for the first time,” he notes, “in an area around the equator.”

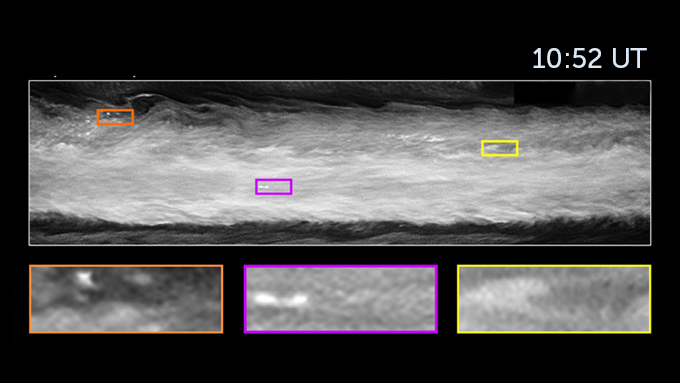

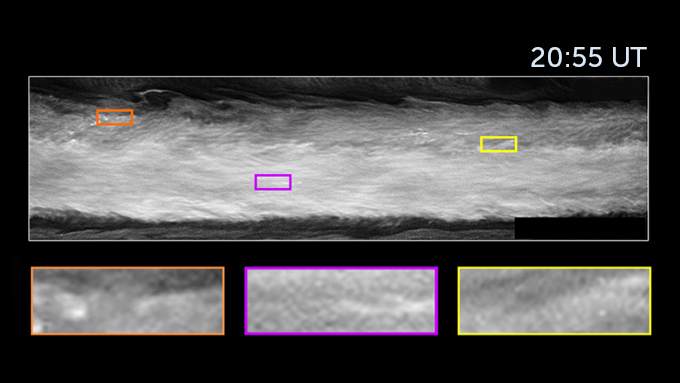

The high-resolution images showing it are “stunning,” says Liming Li. A planetary scientist at the University of Houston, in Texas, he also did not take part in the new work. Hueso’s team compared two snapshots taken 10 hours apart. Those images showed spots and streaks in Jupiter’s atmosphere. Based on how they shifted between the shots, the team could clock the jet stream’s speed.

-

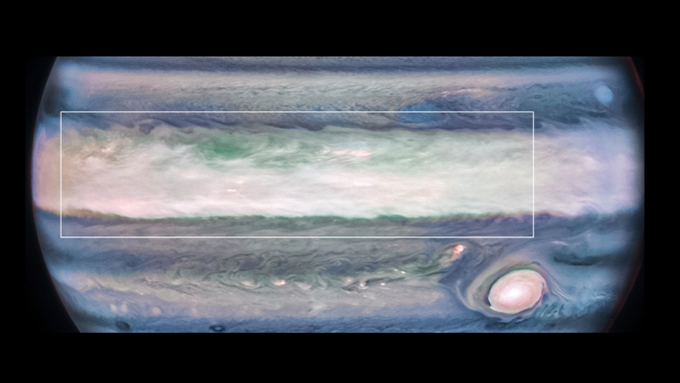

This photo was taken using infrared light. Brighter objects lie at Jupiter’s higher altitudes in this false-color image. The box highlights part of a band of clouds above the equator. Here, researchers noticed several bright features some 20 to 40 kilometers (12.4 to 24.8 miles) above the clouds. NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, R. Hueso/Univ. of the Basque Country, I. de Pater/UCB, T. Fouchet/Observatory of Paris, L. Fletcher/Univ. of Leicester, M. Wong/UCB, J. DePasquale/STScI -

In this snippet from a July 2022 JWST image, three bright features (colored boxes) appear above the clouds over Jupiter’s equator. Tracking those spots and streaks over time let researchers clock the movement of the newly identified jet stream. NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, R. Hueso/Univ. of the Basque Country, I. de Pater/UCB, T. Fouchet/Observatory of Paris, L. Fletcher/Univ. of Leicester, M. Wong/UCB, J. DePasquale/STScI -

This image of the same area 10 hours later shows Jupiter after one rotation. It reveals that the bright features have shifted their positions. That movement led scientists to determine that the newly identified jet stream moves at about 500 kilometers (311 miles) per hour. NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, R. Hueso/Univ. of the Basque Country, I. de Pater/UCB, T. Fouchet/Observatory of Paris, L. Fletcher/Univ. of Leicester, M. Wong/UCB, J. DePasquale/STScI

Future observations of this jet and others could help untangle the tricky physics above the equators of planets, Hueso says. Earth and Jupiter turn swiftly. Their fast rotations create Coriolis forces. These forces steer wind currents to their right in the Northern Hemisphere and to their left in the South. But Coriolis forces don’t exist at the equator, so other factors are at play. And little is known about them. With more investigation, researchers hope to refine the math that describes the atmosphere around the equator.

“We understand the physics of other latitudes,” Hueso says. “It’s the same physics that occur in the atmosphere of the Earth.” But at the equator, “we don’t understand it on Jupiter.” And, he adds, “we don’t understand it on the Earth at the level that we would like.”