(for more about Power Words, click here)

atmosphere The envelope of gases surrounding Earth or another planet.

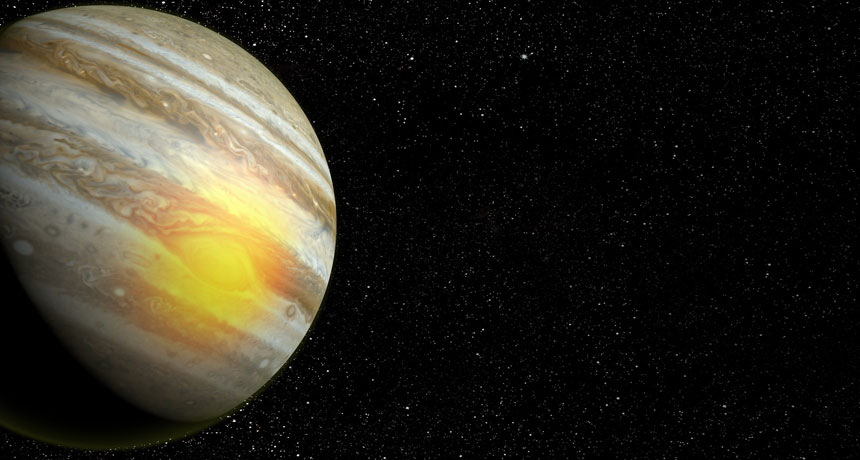

Jupiter (in astronomy) The solar system’s largest planet, it has the shortest day length (10 hours). A gas giant, its low density indicates that this planet is composed of light elements, such as hydrogen and helium. This planet also releases more heat than it receives from the sun as gravity compresses its mass (and slowly shrinks the planet).

latitude The distance from the equator measured in degrees (up to 90).

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (or NASA) Created in 1958, this U.S. agency has become a leader in space research and in stimulating public interest in space exploration. It was through NASA that the United States sent people into orbit and ultimately to the moon. It has also sent research craft to study planets and other celestial objects in our solar system.

planet A celestial object that orbits a star, is big enough for gravity to have squashed it into a roundish ball and it must have cleared other objects out of the way in its orbital neighborhood. To accomplish the third feat, it must be big enough to pull neighboring objects into the planet itself or to sling-shot them around the planet and off into outer space. Astronomers of the International Astronomical Union (IAU) created this three-part scientific definition of a planet in August 2006 to determine Pluto’s status. Based on that definition, IAU ruled that Pluto did not qualify. The solar system now includes eight planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

sound wave A wave that transmits sound. Sound waves have alternating swaths of high and low pressure.

sun The star at the center of Earth’s solar system. It’s an average size star about 26,000 light-years from the center of the Milky Way galaxy. Or a sunlike star.

telescope Usually a light-collecting instrument that makes distant objects appear nearer through the use of lenses or a combination of curved mirrors and lenses. Some, however, collect radio emissions (energy from a different portion of the electromagnetic spectrum) through a network of antennas.

turbulence The chaotic, swirling flow of air. Airplanes that run into turbulence high above ground can give passengers a bumpy ride.

wave A disturbance or variation that travels through space and matter in a regular, oscillating fashion.