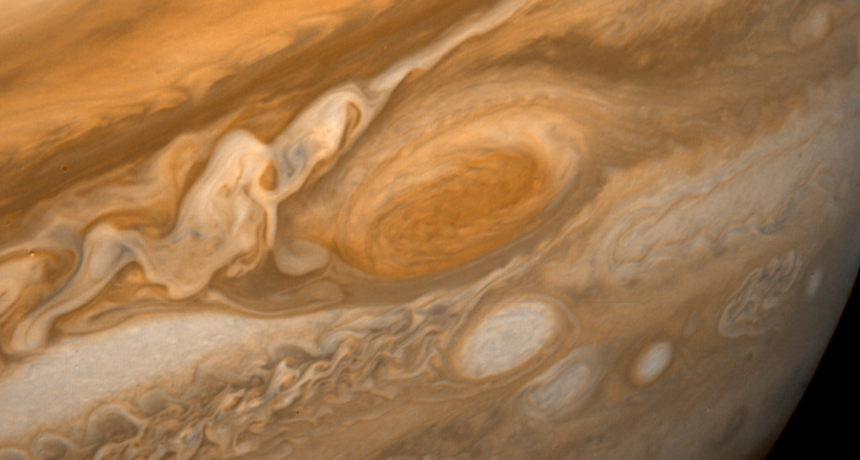

Jupiter’s long-lasting storm

Scientists think they understand why Jupiter’s Great Red Spot doesn’t die

Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a massive storm, is nearly twice as wide as Earth and has been mystifying scientists for almost 200 years. Now physicists have sketched out an idea for how the storm gets the energy to keep raging.

JPL-CALTECH/NASA

Jupiter, the largest planet in the solar system, hosts one of the largest known storms. Nearly twice as wide as Earth, this storm looks like a big, reddish-brown eye in Jupiter’s southern hemisphere. It’s known as the Great Red Spot. Its winds have churned at least since the storm was first observed. That was nearly 200 years ago. Most studies predict it should have fizzled out ages ago. But a team of scientists now says that gases flowing vertically — meaning up and down — may explain the storm’s surprising staying power.

“We have lots of publications that show how the Red Spot dies,” Philip Marcus told Science News. He is a computational physicist at the University of California, Berkeley. Computational physicists like Marcus use mathematics and computer programs to test ideas in physics, the study of energy and matter.

Marcus and Pedram Hassanzadeh, a physicist at Harvard University, used math to build a computer model, or simulation, of the Great Red Spot. Their calculations may finally explain the spot’s longevity.

Gases exit the swirling storm at both its top and bottom, their model suggests. These gases then pick up energy from nearby jet streams — strong, narrow air currents that blow through the atmosphere — before plunging back into the storm. This cycle may help keep the storm going, year after year, say the scientists. The pair presented its findings November 25 at a meeting of physicists in Pittsburgh.

Saturn, Jupiter and Earth all have jet streams. They sometimes lead to the formation of whirlwinds called vortices. (Tornadoes are one example of vortices.) Astronomers once thought that the Great Red Spot — a giant vortex — gained energy by swallowing up smaller vortices spun off by jet streams. But studies in the last few decades had suggested that Jupiter’s jet streams don’t make enough vortices to power the big one.

Previous studies have considered only winds that blow across the planet. Marcus and Hassanzadeh took a different approach. They included precise calculations of winds that blow vertically through and near the big red spot. When they included those vertical winds in their model, it showed the storm had enough oomph to keep spinning for as long as 800 years.

That means Jupiter’s big storm could be around for a long, long time. (Or not: Scientists still don’t know when it started.)

Physicist Robert Ecke at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico called the idea that vertical winds keep the spot spinning “very reasonable.” He told Science News that though the new findings need to be examined by other scientists, they open a window on a new way to think about giant vortices.

Power Words

computational physics The use of computer models, or simulations of complex, real events, and mathematics to test and study ideas from physics.

computer model A program that runs on a computer and creates uses math to create a model, or simulation, of a real-world phenomenon or event.

jet stream A narrow current of air that races through the atmosphere, usually from west to east.

physics The scientific study of the nature and properties of matter and energy.

simulation An event or process that serves as a working imitation — or model — of the real thing. Many simulations are now developed by computers to provide a virtual (computer) model of an event, such as a storm or the burning of a fuel.

vortex (plural: vortices) A swirling whirlpool of some liquid or gas. Tornadoes are vortices, and so are the tornado-like swirls inside a glass of tea that’s been stirred with a spoon. Smoke rings are doughnut-shaped vortices.