Today’s nico-teen addicts: What role does ‘juuling’ play?

Experts worry that the high nicotine in pod-like e-cigs boost addiction and other health risks

JUUL and other brands of podlike e-cigarettes have become the most popular vape in the United States, especially among U.S. teens (despite them being illegal for minors.)

LMWH/iStock/Getty Images Plus

By Janet Raloff

Parents may not recognize on sight a JUUL or similar pod-type electronic cigarette, but many of today’s tweens and teens will. These have quickly become the leading vapes of choice for the legions of U.S. e-cig users 18 and under. Vaping isn’t a healthy choice for anyone. And, new data show, these pod-type e-cigs might just be the worst choice of all for kids who have decided to experiment with tobacco products.

U.S. minors cannot legally buy vapes. And that’s one reason the majority of them find these pod-like devices so appealing, says Bonnie Halpern-Felsher. She’s a developmental psychologist at Stanford University in California. These pod vapes have a deceptively large amount of nicotine, she notes.

That nicotine can harm the developing brain, adds Suchitra Krishnan-Sarin. Whether kids know it or not, their brains will undergo a lot of developmental changes between the ages of 10 and 25. Krishnan-Sarin works at the Yale University School of Medicine, in New Haven, Conn. There, she studies how nicotine affects smokers and vapers.

Most nicotine research has taken place in rodents. “In adolescent animals,” she notes, “nicotine is a neurotoxin.” It keeps the brain from maturing normally during adolescence. This can harm the ability to learn, to make memories and to maintain attention, she explains. It can even lead to hyperactivity.

Krishnan-Sarin spoke at a news briefing for reporters earlier this year. Adolescent animals, she noted, “are very sensitive to even low levels of nicotine.” And that, she explained, “means they get addicted very easily.” The same, she added, is likely true for human teens.

Yet some kids aren’t aware that pod-like e-cigs contain any nicotine. That was one finding of a new survey. At an October workshop at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., Halpern-Felsher and her Stanford colleague Karma McKelvey shared data from their survey of 445 teens and young adults. Each had been asked whether they knew about — or used — pod-like e-cigarettes. The researchers focused on such devices, they said, because JUUL now accounts for between 70 and 85 percent of e-cigarettes vaped in the United States.

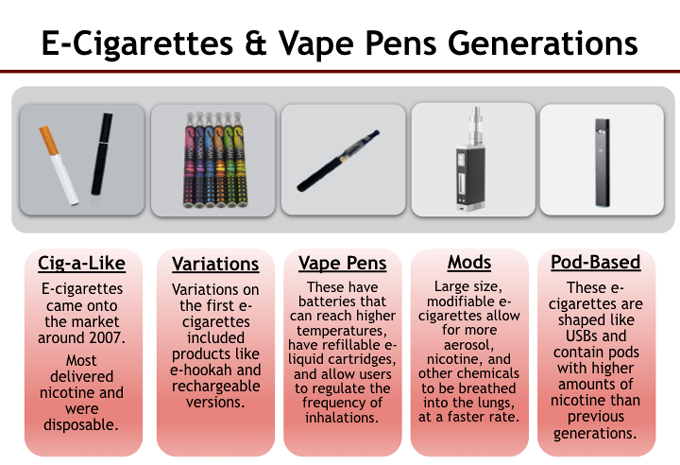

Nearly one-quarter of the students said they had vaped. Of those, more than half said they had used JUUL or other pod-like e-cigs. These devices all are really small. And they don’t look like earlier types of e-cigs. Those had resembled mechanical cigarettes or were clunky. JUUL’s sleek pods look a bit like thumb drives. What’s more, they release a relatively small cloud of the vapors from which vaping takes its name.

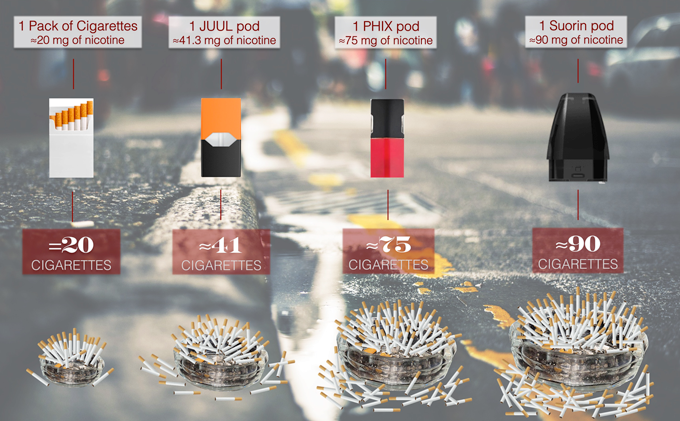

But these devices hold more nicotine than most earlier e-cigarettes, says Halpern-Felsher. Each JUUL pod, for instance, contains 41.3 milligrams. That’s as much nicotine, she notes, as someone can get smoking 26 to 40 conventional cigarettes (depending on how they are puffed).

Moreover, the salt-based form of nicotine in the pods feels less harsh than the nicotine in true cigarettes and earlier e-cigs. So the pods’ nicotine is less likely to turn off a new user, Halpern-Felsher says. And that may encourage kids to overdo it as they experiment.

Some kids are already paying a high price for their covert vaping. Data released Dec. 18 by a federally funded study — Monitoring the Future — finds that 8.1 percent of U.S. 12th graders say they are hooked on vaping. That’s more than twice the 2018 number. What’s more, Halpern-Felsher has found, most teens “don’t recognize how addicted they are.” Some nicotine addicts she surveyed didn’t realize they were hooked at all.

Yet newly emerging data suggest the nicotine delivery by pod-like e-cigs likely makes them at least as addictive as cigarettes.

‘Juuling’ has become a teen thing

Those pods have become so big that they now define much of teen vaping, note Halpern-Felsher and others. Ask kids if they vape and some may say no. To them, she explains, they’re doing something cooler: “juuling.”

Liam Dell, 17, agrees. He’s seen it throughout his Buffalo, N.Y., community. When scientists at the Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center asked this City Honors School student what his classmates were using, “I said JUUL,” Liam recalls. “You can’t get around it as a high-schooler. You see kids using it as they walk down the street. You see it at friends’ houses. You even see it at school. It’s absolutely everywhere.” Kids describe their use of these devices as juuling, he says.

Even some adults may not view JUUL use as conventional vaping, notes Taylor Reed. She’s a research associate who conducts vaping studies in and around New York City. One of her roles, at New York University Medical School, is setting up in-home visits. “Typically,” she says, “on the phone, I’ll ask an adult if anyone [in their home] uses tobacco or nicotine products. And some will say, ‘No, I juul.” They don’t see a pod as a tobacco product.

But the U.S. Food and Drug Administration does. It describes e-cigs as ENDS — short for electronic nicotine delivery systems. Because tobacco is the source of that nicotine, FDA has ruled vapes as tobacco products. Indeed, e-cigs were developed as a way for smokers to wean themselves off cigarettes. Because smokers are addicted to nicotine, e-cigs would help smokers only if they could supply that nicotine.

Yet many teens who never smoked don’t know that, Halpern-Felsher has found.

But Liam does. In fact, he did a study of JUUL’s nicotine as part of his sophomore science fair project. We caught up with him in Pittsburgh, Penn., where his work was being judged as part of the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair. (That fair is a program of Society for Science & the Public, which publishes this magazine.)

Small device, big hits

For his chemistry analyses, Liam used instruments at that nearby Roswell Park cancer center. He confirmed that JUUL vapors carry more nicotine than standard e-cig vapors. His data also show they dispense what he describes as “a more addictive form” of nicotine. Known as non-ionized (Non-EYE-oh-nyzed) salts, it “is able to bond more easily to your lungs and to your brain,” he says. “So you could say it sticks more.”

The manufacturer “doesn’t seem to hide the fact that JUUL dispenses high levels of nicotine,” Liam says. It’s on the label. However, the label does not mention what chemical form this nicotine takes. Liam found that “99.4 percent of the nicotine salts were in the non-ionized form. That’s just ridiculously high.” For comparison, he says, “nicotine in e-cigarettes is typically around 80 percent un-ionized.”

He didn’t measure how much of that nicotine ends up in the body. That’s what Jessica Yingst and Jonathan Foulds have just done. These public health scientists work at Penn State Cancer Institute in Hershey. They headed a team that measured blood levels of nicotine before, during and after someone had smoked a cigarette or had taken 30 puffs from an e-cig over a 10-minute period. All the vapers were former smokers.

The vapers used their own devices. In the first of these studies, those recruits used early models of e-cigs. A few of the vapers used so-called cig-alikes (which look somewhat like cigarettes). The rest used advanced “mods.” These allowed users to choose the flavor of liquid they vaped.

Blood levels of nicotine rose as someone vaped. But that average rise (8.2 nanograms per milliliter, or ng/ml) was far lower than in the 10 smokers who each puffed normally on a single cigarette (about 21 ng/ml).

That was “a bit of a surprise,” says Foulds. After all, some of these pre-JUUL devices had vaporized liquids that contained a lot of nicotine. The only explanation, he says, was that these e-cigs “just didn’t deliver nicotine efficiently.”

His team published its findings July 25 in PLOS One.

These data, Foulds realized, might explain why many smokers who had tried vaping went back to cigarettes. Perhaps they just didn’t get a big enough hit of nicotine to sate their cravings.

To test this, his team ran the same trial in six JUUL users. And as soon as the blood data came back, Foulds says, “We went, whoa! That’s a lot of nicotine.” The rise averaged some 28.6 ng/ml.

The Penn State team reported these findings November 15 in JAMA Network Open.

Addiction becomes a real threat

That was a small survey, Yingst admits. Still, she notes, “the nicotine delivery in all six people was pretty similar.” That suggests, she says, they were getting far more nicotine than do users of earlier types of e-cigs. In fact, these new data show, “JUUL delivers nicotine very similarly to a cigarette.”

The company that makes these pods knows that, Foulds adds. His team’s new data are “comparable to what [JUUL Inc.] found in its unpublished data,” he says. The company referred to those data in its patent, he found. He notes that, “[The company] also presented it in a poster at a conference we were at.”

So if these devices deliver as much nicotine as a cigarette, Yingst says, they “would have a similar potential to cause addiction.” In fact, Yingst and Foulds also have just measured the extent to which the JUUL users experience symptoms of addiction. Penn State has a special survey to measure that in users of tobacco products.

Its researchers surveyed cigarette smokers on this 20-point scale. Higher numbers indicate higher levels of addiction. On average, smokers scored a 14, Foulds says. Among users of the pre-JUUL types of e-cigs, the average addiction rating was 8. But among people who vaped JUULs, he notes, the average was 14. These preliminary data now seem to “confirm what many people had suspected,” he says — “that this product is as addictive as a cigarette.”

That should prove as true for teens as for the adults in these studies, Halpern-Felsher says. Yet kids don’t know that, her team finds.

Her group used a different survey to measure addiction. On its 10-point scale, “even scoring a 1 signifies addiction,” she says. And most teen vapers that her team surveyed averaged a 2.5 to 3 on this scale. People who are addicted have a very hard time quitting. Yet these kids don’t realize how dependent they have become on the nicotine they vape.

“They don’t know they’re addicted,” Halpern-Felsher says. “But we do.” She’s published data on this. The young vapers were asked such questions as how quickly did they feel a need to vape after waking? Or did they need to vape even after being told not to use e-cigarettes? “The point is,” she says, “most of today’s youth don’t truly know what addiction means.”

In one October 2018 study, her team assessed how teens and young adults view pod-type e-cigarettes. Ironically, those young people rated the pods “as posing less harm or addictive potential [than other vapes].” At the same time, these so-called juulers showed more nicotine dependence than users of other types of e-cigs.

“It’s just the perfect bad storm,” concludes Halpern-Felsher of juuling.

New trends prompting action

Just eight years ago, teen vaping was virtually unheard-of, note analysts at the Universities of Michigan and Minnesota. They work for that long-running Monitoring the Future program, which has been tracking teen substance abuse for 45 years. Last January 10, they wrote a letter that appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine. In it, they noted that the current growth in vaping seen in high school teens is the greatest jump in nicotine exposures that their program has witnessed in 44 years. Today, more than one in four U.S. high school seniors has at least tried vaping in the past month. The survey’s just-released 2019 data show that more than one in 1 in 10 of these kids now vape daily. Nearly the same share of 8th graders now report they’ve vaped in the past month. Indeed, the number of kids who began vaping at or before the age of 14 has more than tripled in the past five years, the new survey finds.

Some states, New York included, have raised to 21 the age at which people can buy vape products. But that hasn’t slowed the rise in teen vaping. Doctors and others are aggressively looking to reverse this trend.

Patrice A. Harris is one of them. This physician is president of the American Medical Association. On November 19, she issued a statement saying, “It’s simple — we must keep nicotine products out of the hands of young people.” That, she explained, is “why we [the AMA] are calling for an immediate ban on all e-cigarette and vaping products.”

On the same day, Letitia James filed a lawsuit against JUUL Labs, Inc. As the attorney general of New York, she has a lot of clout. Her state’s lawsuit charges that “JUUL’s aggressive advertising of its multi-flavored products has contributed to a public health crisis.” Indeed, it argues, this crisis “has left countless New Yorkers — many of them teenagers — addicted to its products and fighting for their health.”

California’s attorney general also sued JUUL. His office and the city of Los Angeles also argued that this company and other pod-makers have targeted kids. “JUUL and other nicotine product makers must be held accountable” for not preventing sales to underage users, says Los Angeles District Attorney Jackie Lacey.

“There can be no doubt that JUUL’s aggressive advertising has significantly contributed to the public health crisis that has left youth . . . across the country addicted to its products,” noted James. The company’s advertising has been “glamorizing vaping, while at the same time downplaying the nicotine found in vaping products,” she added. “I am prepared to use every legal tool in our arsenal to protect the health and safety of our youth.”

Halpern-Felsher’s team has its own Tobacco Prevention Toolkit aimed at doing this. Its materials can be downloaded free from the Stanford School of Medicine’s website. They describe a wide range of non-cigarette products that can hook kids on nicotine. They also explain how the toolkit can be used to better inform today’s tweens and teens on those risks — hopefully, before they get hooked.