Keeping space missions from infecting Earth and other worlds

Spacecraft can move germs between planets, so cleanliness is key

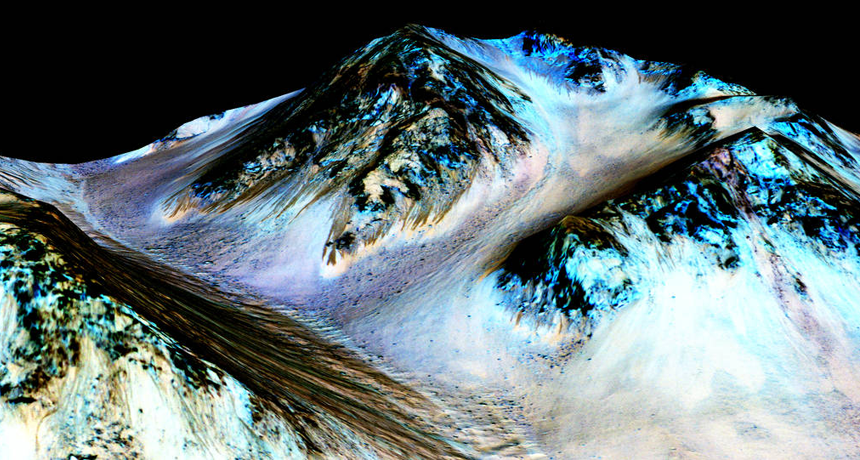

This false-color image was taken by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, showing Hale Crater. Scientists think the dark, narrow streaks shown here might be signs of flowing water on Mars. If there’s water, there also might be a chance for life.

University of Arizona/JPL/NASA

BOSTON, Mass. — In the new movie Life, astronauts engage in an epic battle to protect Earth. The team is studying an organism from a sample of Martian soil. But this creature isn’t as cute as it first appears. It is strong and smart and eventually threatens to destroy the space station and take over Earth.

This is science fiction. But there may be some nugget of truth to the situation. “We don’t know what we don’t know,” explains Norine Noonan. She’s a biologist at the University of South Florida in St. Petersburg. Robots or astronauts may one day encounter organisms on other worlds. If they do, they might also bring them home to Earth — maybe not even on purpose. Like an infection or microbial weed, those alien species could have the potential to flourish on Earth. They might even displace one or more of Earth’s own species.

Noonan described what’s at stake, here, at the American Association for the Advancement of Science annual meeting on February 17.

NASA is planning for sample-return missions in the not-so-distant future. These missions would retrieve dirt, dust or other bits of a planet or moon and bring them to Earth for study. If that happens, the space agency will need a range of experts to advise it on how to handle the samples safely. For instance, they would have to look into preventing any life that may be brought back from infecting species on Earth. And because Earthly life would be aliens on Mars, NASA can’t risk infecting the Red Planet or any other worlds that its missions visit.

The issue has become a growing concern as biologists have uncovered species on our planet able to survive extreme environments. These organisms are called extremophiles (Ex-TREE-moh-fyles). Some live deep underground in caves. Others make their homes on volcanoes or in the hot waters of Yellowstone’s geyser pools.

“We know so little about extremophiles on Earth,” Noonan says. In fact, she points out, scientists have yet to identify most bacteria on our planet. So if the experts don’t know much about what is here, how can they hope to know what might be living on distant worlds or their moons? Some alien critter might be barely surviving at home — but poised to grow like gangbusters in Earth’s environment. So bringing it home could prove quite risky.

An old and increasingly costly worry

Scientists first started considering what Earth-life they might be sending into space following the 1957 launch of Russia’s Sputnik — the world’s first satellite. As missions became more advanced, scientists started calculating just how many microbes might stow away on spacecraft. The idea was to keep the numbers low so that few of these terrestrials would be available to make themselves at home on any extraterrestrial site.

In the 1970s, NASA sent two sets of orbiters and landers to Mars. These Viking missions were to search for life on the Red Planet. But NASA didn’t want to risk traveling all that way just to later “detect” some Earthly germ it had accidentally launched into space, notes Cassie Conley. She is a planetary protection officer at NASA’s headquarters in Washington D.C. Before each spacecraft launched, it was baked in an oven. The hope was that this heat would kill most germs on board.

The goal, she explains, was to keep the total to fewer than 30 viable organisms on the entire outside surfaces of the spacecraft.

It’s now Conley’s job to think about how to keep Earth’s microbes from infecting Mars and beyond. That includes places like Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus.

For now, though, she is focusing on keeping Mars “clean.” After the Viking landers failed to find hints of life on Mars, NASA relaxed its requirements about sterilizing spacecraft prior to launch. But in the past few decades, there’s been growing evidence of water on Mars. And where there’s water, there could be life. Concern has been building, Conley says, that spacecraft cleanliness requirements may have been “relaxed a little too far.”

That’s led to a lot of discussion about how to clean the next round of spacecraft headed to the Red Planet. And that disinfection is no small deal. Ten percent of the total cost of a mission can be spent just to remove germs, Conley says. Justifying anything that costly “leads to tension,” she adds.

Scientists want as many instruments as possible on a spacecraft. But at 10 percent of the cost of a billion-dollar mission, germ removal alone might run to millions of dollars. That can be as much as a major science instrument. So there can be a tug-of-war between doing science and keeping the spacecraft clean, she says.

There’s also a lot of talk about what to do when astronauts go to Mars. Humans spew lots of microbes into the air around them. Figuring out how to keep those germs from infecting the Martian environment will be important, too.

Spending the money to keep extraterrestrial worlds clean is essential. “We don’t understand all of the consequences of moving organisms around,” Conley says. “We want to put protections in place before we have the chance to make mistakes.”

Some scientists might argue that missions to Mars have already polluted the planet, so why worry about doing better now, she notes. But her response: “That’s like stopping brushing your teeth after you’ve eaten your first candy bar.” It doesn’t happen. You just brush again, she says — and maybe better — “because it’s a good idea.”

Planetary protection, she adds, requires the same constant attention to germ-control.