A first: Kids advise hospital researchers on their medical studies

Realizing it was missing key voices, the Mayo Clinic set up a kids-only advisory board

A teen on the Mayo Clinic’s pediatric advisory board voices her opinion at a July meeting in Minnesota.

Courtesy of Mayo Clinic

Paul Croarkin paces in a conference room as he presents a slideshow. It showcases his latest research on depression.

A psychiatrist, he works at the Mayo Clinic, a hospital in Rochester, Minn. And he’s excited. It’s the first time he’s described his research to the hospital’s newest advisory board. He really wants the board’s opinions and feedback so that he can improve his study.

The board members pay close attention and offer great ideas. After all, that’s their job. But they look a little different from most hospital board members. All are children and teens. They make up the only medical pediatric advisory board in the United States. The Mayo Clinic formed this group after it realized that hospitals could be missing important ways to help children’s social, emotional and physical health. Scientists don’t often ask kids what they need from research — even though there is a lot of medical research that can affect them.

Tiera Felder, 17, signed up as soon as her parents told her about the Mayo Clinic’s new advisory board.

She recalls: “I was like, I can pass two hours helping the community instead of sitting around the house? Yes, please!” She notes that she dragged her brother along as well.

Isaiah Alexander, 15, also is glad that doctors are listening to youth.

“I think doctors haven’t been teenagers in a very long time, so maybe their outlook on something [isn’t accurate],” he says. “Maybe they’ll think it’s the same as [when they were young] and use a biased opinion on forming a hypothesis on something.”

The Aha! moment

Another doctor at the Mayo Clinic, Christi Patten, came up with the idea for this board after a meeting of the Mayo Clinic’s adult advisory board. (Most hospitals have adult advisory boards to help doctors and researchers make good decisions.) That day, some researchers had presented information about their work on physical activity among underserved youth in Minneapolis. Patten talked to the program manager afterward.

“The adults gave great feedback, but it made us think about involving youth,” she says. “There was more research coming to our board focusing on kids, so it struck us that we needed the perspectives of youth.”

Many doctors and researchers at the Mayo Clinic want feedback on their pediatric research. So it made sense to talk directly to kids.

The community engagement team at the Mayo Clinic agreed. (That group works to make connections with people who live near the hospital.)

Patten couldn’t find any other U.S. hospitals that had a board made up of kids. Once the Mayo Clinic got an official okay to start one, organizers started looking for kids who wanted to serve on the board.

They found about 20 kids between the ages 11 and 17. All agreed to attend meetings four times a year. They convened for the first time last April to meet and start their training.

To be on a board for a hospital, you need to know a few things about how studies of medical treatments work. Those studies are called clinical trials. At the first meeting, the kids learned about how people who participate in clinical trials are protected. Doctors and researchers need to make sure that participants really want to be in a trial before they sign up. It wasn’t always that way. During World War II, for example, Nazis conducted experiments on prisoners without their consent. And in the United States, scientists failed to give the 600 black men who agreed to be in the Tuskegee Study all the facts — or appropriate treatment for their disease. That study was ended in 1972 when a government panel found it to be unethical. By then it had been underway for more than 40 years!

Summer session

At their next meeting, in July, the board members got their first chance to give feedback to researchers when they met with Croarkin. (The kids also offered some important feedback about meetings: The snacks should be good.)

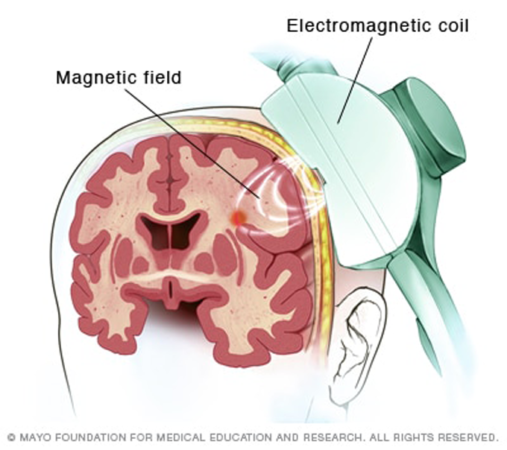

That evening, dressed in the navy blue suit and purple striped tie that he’d worn to work, Croarkin clicked through his slideshow. He’s trying to help kids and teens with depression. The medication currently used for this disease doesn’t work in a lot of patients, he explained. So he is testing a new treatment. It’s called transcranial (Trans-KRAY-nee-ul) magnetic stimulation, or TMS. Scientists think it works because it activates regions in the brain that affect mood.

In TMS therapy, a doctor places an electromagnetic coil on a patient’s head, like a hat. Hooked up to a machine, the coil pulses. It feels like a light tapping on your skull, Croarkin explained to the board. The machine can make fast or slow pulses, and this doctor is trying to see if one works better than the other. But he has a problem. He needs more kids to participate.

He asked the board for help. “What do you think? How can we get the word out?”

The kids had some questions of their own first. “Is depression cured after you do it once or do you have to keep doing it?” Isaiah asked. Another boy wanted to know how much it costs. Later, Croarkin said that those questions are important because it helps him understand the types of questions adolescents have about TMS.

Then Croarkin passed around a flier he’d made to advertise the study.

“What does everyone think of the flier?” he asked.

The kids had lots of ideas.

First of all, the wording should be directed at kids — not adults, they said. A kid with depression might be more likely to respond if he or she saw the poster rather than being told about it by a parent.

“You don’t really have to dumb it down,” Isaiah said. “It’s just that teens aren’t going to want to sit down and read all these medical terms.”

Tiera agreed. “Make it as simple as you can, like the way you explained it to us.”

“Does the picture of the brain freak you out?” Croarkin asked. The general consensus was no. But no one was too sure that it’s helpful, either.

He asked if there was a better way to reach kids directly.

“Try social media,” Tiera suggested.

Croarkin was eager to know which apps to use. The kids’ answer: Instagram and Snapchat.

Of course, Tiera noted, most kids might not follow Mayo’s Instagram, so the kids also suggested fliers at the library or in the office of the school social worker.

Afterward, Croarkin called the kids’ opinions “invaluable.” Other researchers are eager to meet with the kids, too. It’s an important reality check for researchers, says Miguel Valdez Soto. He is an organizer of the board. If a scientist can find out that kids aren’t interested in a certain topic, for example, it can save that researcher a lot of time and money. In fact, the organizers say that so many researchers have requested to meet with the board that they may have to add more meetings.

Good for researchers and kids

The board met again in October, when a researcher asked for suggestions on how to make doctor appointments less intimidating for kids.

The Mayo Clinic is hoping that other hospitals will follow its model and create their own kids’ boards. Pediatrician Young Juhn leads the board with the help of Patten, Valdez Soto and others. “Over time,” Juhn says, “once we see the impacts, we’ll see if it’s worth spreading this to other sites.”

After a year, their team will evaluate how successful the program has been by asking the researchers if and how they used the board’s suggestions. But they already know the program has been successful in another way, Juhn says. The kids have learned the process and ethics of running scientific research.

“It’s a cool opportunity and maybe it’ll open more doors for me in the future,” Isaiah says.