U.S. lawmakers look for ways to protect kids on social media

Senators grilled company heads about how their sites have let users badly harm kids

Gen Zers spend much of their lives on social media, often responding more to their devices than to the people beside them. Though many online posts are fun, supportive and informative, others can be hurtful, dangerous or exploitative. Government officials are now looking to protect kids from those harmful posts.

Peter Cade/Stone/Getty Images Plus

Nate Bronstein loved basketball and played the drums. Yet nasty texts and Snapchat messages threatened the Chicago, Ill., teen. They urged him to harm himself. As the abuse continued, Nate’s mental health worsened. One day in early 2022, the 15-year-old killed himself.

Twelve-year-old Matthew Minor was scrolling online one night after dinner. The Maryland boy found a TikTok video about a choking dare. Matthew tried it. He probably thought he would just pass out. Instead, he died.

On January 31, the parents of these boys and dozens of other grieving family members packed a U.S. Senate hearing room in Washington, D.C. They came to listen as lawmakers questioned the heads of five large social media companies.

Those senators want to protect kids who surf the Web. The hearing highlighted many ways that kids have been hurt through their use of social media. Several laws have been proposed to address these issues. It’s unclear whether any proposals will become law this year. But it is clear social media sites have played a role in harming children and teens.

Millions of kids use social media — and they use it a lot.

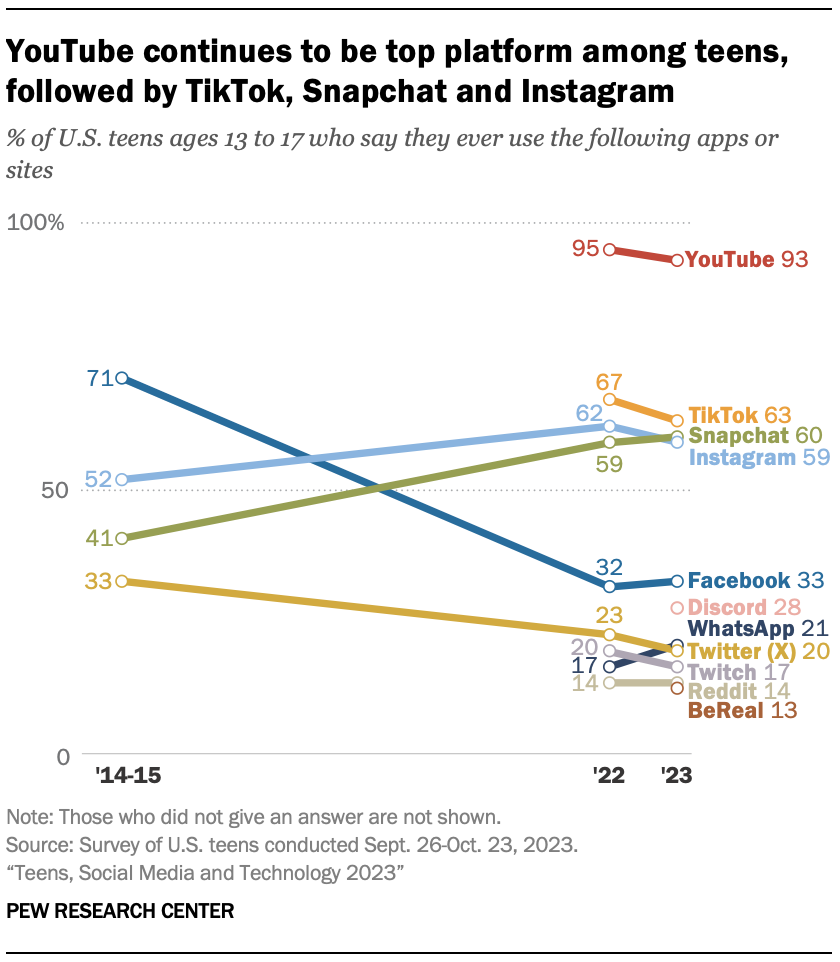

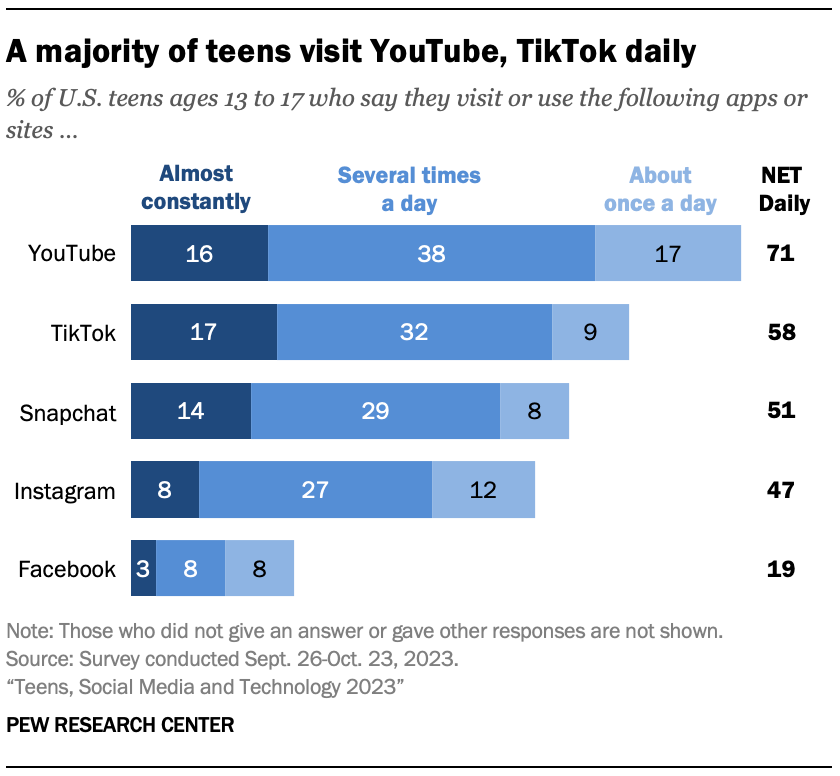

A fall 2023 Pew Research Center survey found roughly nine in 10 U.S. teens use YouTube. TikTok, Snapchat and Instagram are popular, too — used by roughly six in 10 kids from 13 to 17 years old. About one-third of teens that age also use Facebook and X (formerly known as Twitter).

The overall impacts of teens’ social media use are mixed. Some studies have linked it to higher risks for teen depression, anxiety and self-harm. Other studies have linked some social media use in young students with positive impacts.

Such conflicting data make it tricky to write protective laws. And, experts add, new laws might not be the whole answer.

Lawmakers presented evidence of harm

A short video at the hearing shared stories of children who had been hurt through social media. The senators pointed to dozens more cases. Some, like Nate, were victims of cyberbullying. Other kids’ social media feeds had been flooded with material glorifying violence or urging them to harm themselves.

Predators also lied and exploited children in other ways. In some cases, people faked a romantic interest to trick a child or teen into sending a compromising photo. Predators then posted the images online. Or they used blackmail: They threatened to post those photos to family and more if the kids didn’t send them huge sums of money. That’s a crime known as extortion.

The January 31 hearing in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee called in the heads of five social media companies. Jason Citron leads Discord. Evan Spiegel helms Snap. Shou Zi Chew heads up TikTok. Linda Yaccarino is the chief executive officer of X. And Mark Zuckerberg runs Meta; it owns Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp. Their sites could do much more to prevent or take down abusive material — but don’t, the senators charged.

Companies say they already protect kids

Sen. Marsha Blackburn of Tennessee noted that some Meta documents estimated a lifetime benefit to the company of $270 for each teen who uses its sites. Then she named four child victims from her state. “Would you say that life is only worth $270?” she asked Zuckerberg of Meta.

In 2021, U.S. senators brought in a former Facebook employee to explain how Facebook and Instagram worked to keep younger users scrolling and clicking. Frances Haugen, the whistleblower, said her company had continued to lure kids into excessive use of the sites — even after its own research showed teens’ mental health often suffered.

“Your companies cannot continue to profit off young users only to look the other way when those users — our children — are harmed online,” Sen. Mazie Hirono of Hawaii told the company leaders at the January hearing.

Prompted by another senator’s question, Zuckerberg turned to grieving family members. “I’m sorry. Everything you have all gone through, it’s terrible,” he said. “No one should have to go through the things that your families have suffered.”

Yet he did not take responsibility for the harm. Instead, he said, his company had made “industry-leading efforts” to ensure “no one has to go through the types of things that your families have had to suffer.”

Other company heads also said they’ve been hard at work to limit harm.

Scanning technology works to block images of child sexual abuse on Discord, Citron said. And messages on this site aren’t fully encrypted. That means Discord can help with requests by law enforcement to see posts, he said — and who’s responsible for them. Yaccarino of X claimed the company has zero tolerance for material that features or promotes sexual exploitation of kids.

The Senate recorded its four-hour January 31, 2024, hearing on Big Tech and the Online Child Sexual Exploitation Crisis. You can watch the hearing and read witness testimony at the link.

Chew said TikTok only lets people 13 and older use its site. Accounts are set to private for anyone under 16. And other users can’t send young teens direct messages. Users under 18 have a 60-minute limit on screen time, he added. And they can’t use livestream.

Spiegel of Snapchat said friend lists and profile photos for its platform aren’t public. This, he said, should “make it very difficult for predators to find teens.” There also are parental controls, he added. Yet only about 400,000 out of 20 million teens have accounts linked to their parents, he said. That’s just 2 percent.

In fact, the share of abusive content on any social media site may be small. But the total amount of content is huge. So small percentages can still mean a large number of harmful posts, noted Sen. Chris Coons of Connecticut. And even if data don’t show harm at a population level, he said, “I’m looking at a room full of hundreds of parents who have lost children.”

New restrictions?

So far, U.S. law largely exempts social media companies from legal responsibility for what’s posted on their websites. At the January 31 hearing, the senators said they wanted to change that. They’re also looking at other ways to protect kids.

On February 22, senators introduced the latest version of the Kids Online Safety Act. It would require social media companies to use “reasonable care” to protect users under age 18. Its goal is to reduce bullying, harassment and other abuse that has been linked with depression. Young users’ scrolling and notifications could also be limited.

The bill would also require strict privacy settings for young users. It calls for limiting whom kids and teens could communicate with. Other terms would expand parents’ control over a child’s accounts. Reporting problems and deleting kids’ accounts would be easier, too.

Some U.S. states have passed their own social media laws, including Ohio, Arkansas and California. Other states are considering bills. Common terms call for verification of users’ ages, parental consent for younger teens, parental monitoring tools and more. However, some of the new state laws have not yet gone into effect. The reason for some delays: A tech industry group sued to block the laws.

Other countries also are acting to protect young social media users. For example, the European Union’s Digital Services Act calls for features to reduce kids’ time on social media. It also bans advertising targeted at kids. India and Brazil require parents’ consent before kids can legally access sites that collect or process kids’ data. China also limits kids’ time online and what they can see. That’s in addition to China’s more general total block on all access to some social media sites.

Anna B. lives in Missouri. She began accessing social media when she was 10. Now 17, she worries about privacy if social media sites try to establish a user’s age. Will they ask her to upload a driver’s license, birth certificate or other proof of age? “That’s just really sensitive information that I don’t feel comfortable giving a private company,” she says.

Anna also questions time limits on screen time. Some posts can still make her feel self-conscious, even if she’s only online for a short time. And if she’s been offline for a while, a bunch of notifications can feel “like an information overload” when she returns.

High initial privacy settings would be okay with 14-year-old Stevie H., who lives in Arizona. She thinks many teens put too much personal information on their social media profiles. “No one should really know that information unless they actually know you,” she says.

Stevie also uses one of her social media accounts for a handicrafts business. And she’s in touch with people around the world who also work in her field. So limits on her online messaging abilities might pose an unwelcome challenge, she told Science News Explores.

Both teens have seen things on social media that they feel are awful. And both want social media companies to take more responsibility for what shows up on their sites.

“Some sort of content supervision would be good,” Anna said.

And Stevie wants “stricter requirements and deadlines for companies to fix problems when people complain about abusive or improper content.”

Both girls say they talk with their parents about various things online. But parents don’t necessarily have time or skills to monitor everything their kids do, Stevie notes.

Adds Anna, “I don’t think micromanagement is the way.”

The Senate hearing focused on how social media has hurt kids. Yet research shows these sites can offer some real benefits, too.

Linda Charmaraman heads the Youth, Media & Wellbeing Lab at Wellesley Centers for Women in Massachusetts. She and others summed up some of social media’s positive and negative impacts on kids’ mental health in a book chapter last year.

On the downside, they point out, cyberbullying can increase risks for self-harm, including suicide. Online drama can heighten feelings of social exclusion. Comparisons can make teens feel they don’t measure up. Comparisons also might raise the risks for body-image problems and eating disorders. Substituting social media use for sleep time or for tackling other important activities are problems, too.

On the plus side, social media can help teens build and strengthen social connections, Charmaraman and her colleagues write. Social media also lets teens explore their interests and identities. And of course these sites provide entertainment and outlets for creative expression, too.

Social media also can give people support they might not get at home or in their communities. Charmaraman has seen that for various LGBTQ+ youth, for example. In some cases, parental controls or new limits on content might make those kids feel less safe, she worries.

Psychologist Jacqueline Nesi sees “two sides of the coin” with social media’s pros and cons. Social media can be “an amplifier of both good stuff and bad stuff,” she feels. Nesi is at Brown University in Providence, R.I. She described some of the challenges and opportunities of social media a few years back in the North Carolina Medical Journal.

More recently, she and others put out a 2023 report: How Girls Really Feel About Social Media. Girls who already face or are at risk for mental-health problems were more likely than other users to have bad experiences online, the team found from surveys. Yet those same kids also were more likely than others to value social media’s benefits. These included finding support or resources or feeling a sense of community.

Such findings make it “really tricky” to develop firm guidelines for safer social media use, Nesi says. It’s also tricky figuring out how much should be regulated by law or dealt with in other ways.

Her group’s survey found many kids want more online security. Many want more options to filter or block contacts, including strangers. Many of the surveyed girls also want social media sites to show both more positive and more age-appropriate content.

“Everybody probably needs to chip in,” Charmaraman says. In her view, tech companies need more regulation than they face now. But she feels that parents and families also have a role to play.

Last December, Charmaraman and others wrote about parents’ different approaches in the Journal of Child and Family Studies. Some parents restrict what social media their kids see and how long they can spend online. Other parents try to avoid limits. Still other parents actively talk with kids about social media. They may discuss things like critical thinking, choices and the implicit (hidden) messages behind posts.

“There’s no one parent-monitoring technique that’s going to work for everybody,” Charmaraman says.

She also thinks kids need more education about media literacy. That teaches people how to analyze and think critically about news and other material in various types of media.

Kids also can work on getting the most from their screen time.

Check in with yourself regularly, suggests Nesi. What parts of social media help you? What things make you feel bad? And what might you want to change about your time online?

“Really try to take a mindful approach to social media use,” she says.

Suicide is the second leading cause of death in the United States for young people between the ages of 10 and 24 years, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics. If you or someone you know is suffering from suicidal thoughts, please seek help. In the United States, you can reach the Suicide Crisis Lifeline by calling or texting 988. Do not suffer in silence.