Lack of diversity in his field has troubled this mathematician

So Edray Goins left a big research university to teach at a liberal arts school

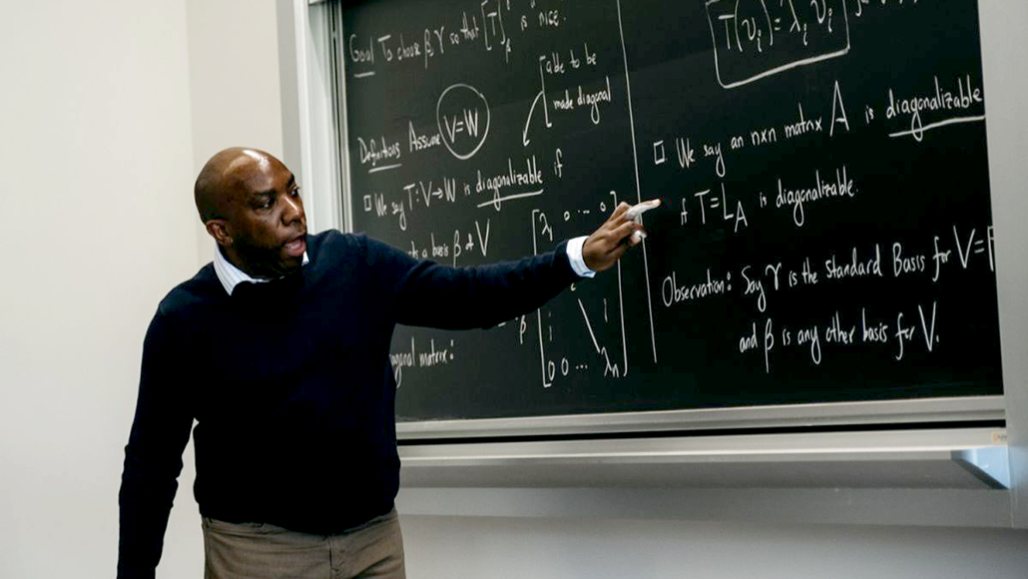

Edray Goins teaches linear algebra at Pomona College — and wants to inspire the next generation of minority mathematicians.

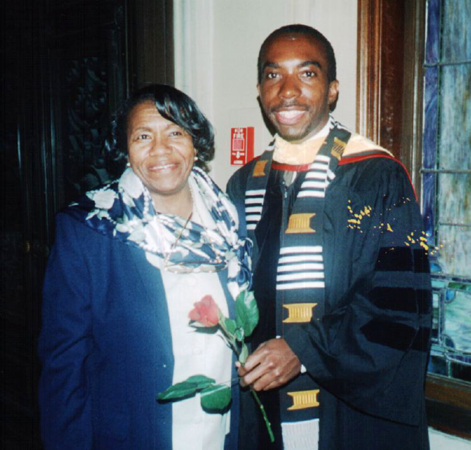

Courtesy of Myles Ashitey

Reaching the top ranks of mathematicians isn’t easy, even when you’re really smart. But Edray Goins managed just that. He works at the intersection of algebra and number theory. He likes studying so-called Diophantine equations. These have certain patterns of integers. One example: “Pythagorean triples,” such as the 3-4-5 right triangle, where three squared plus four squared equals five squared. And don’t worry if you don’t understand that — many adults don’t, either.

In his career, Goins has worked at some of the top universities for math, such as Caltech, Stanford University and Harvard University. But he noticed something. At every one of them, there were few women and minorities, especially Blacks and Latinos. “It’s always depressed me,” Goins says. “I complained about this over the years, saying this isn’t right. Something needs to change. But I realized I can’t complain unless I’m willing to do something about it.”

So last year, Goins took a job as a professor at Pomona College. It’s in Claremont, Calif., not far from where he grew up. He’s still tackling those complex math problems. But his real goal is to help train the women and minorities in college who will be the next generation of scientists and mathematicians. In this interview, Goins shares his experiences and advice with Science News for Students. (This interview has been edited for content and readability.)

What inspired you to pursue your career?

When I was in elementary school, the space shuttle was launched for the first time. Watching that got me fascinated with science and how the world works.

And so, when I went off to college at Caltech in Pasadena, Calif., I majored in physics. During the first few weeks, I saw a book at the campus bookstore entitled Algebraic Geometry. I knew what algebra was. I knew what geometry was. But I’d never heard of “algebraic geometry.” I purchased the book and tried to read it. I saw a few pictures in there that looked pretty but couldn’t comprehend what I was reading.

I purchased a second book, An Introduction to Number Theory. Again, I had no idea what this was. I started to read. One day my calculus teacher said there’s a guy named Harold Stark coming to Caltech to give a series of lectures. This was the guy who wrote the book I was reading — the book about number theory. So I went to the talk. I understood maybe the first 45 minutes. After that I had no idea what he was talking about. But that book and the guy discussing what was in that book — that’s what convinced me to be a math major.

How did you get where you are today?

At first, I was embarrassed to tell people I was majoring in math. I did it to indulge in the subject. I kept the physics major because I figured I could be a physics professor and do research in physics. That was something I could see myself doing. But I didn’t understand the career paths of someone who majored in mathematics. I didn’t tell anyone I was a math major until maybe my third year of college.

I felt very fortunate to be at Caltech. Some of the world’s best physicists were teaching there. For example, Kip Thorne — who won the 2017 Nobel Prize in physics for helping discover gravitational waves — worked on all of this while I was an undergraduate. Seeing that when I was 18, 19 years old motivated me to become a scientist to change the world. I didn’t just want to get A’s in my classes. I wanted to make a huge discovery, to do something that had never been done before.

Then I went to Stanford, in California, for graduate school. I had the time of my life. By my second year or so, I decided I would be a math professor.

To keep one foot in the physics world, I’d also been going to the National Society of Black Physicists conference every year since I was a sophomore. One year it was held at Stanford. As the conference was winding down one night, it was just me and Stanford physics professor Doug Osheroff sitting at a table. I was very intimidated because he had won a Nobel Prize some years before. But you know, he was just trying to be encouraging to people at the conference.

We got to talking, and I told him I was embarrassed that I wasn’t a physics major anymore. I didn’t think I was very good at physics. He asked me about the training I had as an undergraduate. He stopped me at one point and said that I was so good I could’ve entered grad school as a third- or fourth-year PhD student.

No one had ever told me that I was that good. That really gave me a lot of confidence. And now I was saying, “I can really do this.”

What’s one of your biggest failures, and how did you get past that?

I don’t know if “failure” is the right word, but if I could do it all over, there are two things I would do differently. One, I think, is having a family, having kids. I spent a long time saying, “I’m going to focus on the research. I’m going to get these big results. I’m going to become a famous scientist, a famous mathematician.” And I woke up years later and realized, what’s the point? I could spend my whole life doing research, but what am I really doing if I don’t have a life outside of that? I’d say that’s perhaps my biggest failure.

The second thing is, I think I consider taking a job at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., a failure. I knew within my first year that it wasn’t going to work.

I grew up in southern California, a large, sprawling metroplex. There’s lots to do, lots to see — beaches, mountains, the movie culture, the car culture, all of this. Indiana has none of that. There are no large cities, no mountains. And for most people — you go to work, go home at 5 p.m., spend time with your family, that’s it. People don’t go out. And if you’re someone like me who didn’t have a family, you can find that a very difficult place to live.

Also, I hate to say it this way, but Indiana is a racist state. I’m not saying California is not, but you can’t be Black in this country and not know that the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan was in Indiana back in the 1920s. And you see that everywhere. There are Confederate flags. There are these so-called “sundown cities” where, even to this day, if you’re Black, it’s dangerous to be in that town after sundown.

Also, in my department there wasn’t a lot of collegiality. People were there to work. And when they were done, they went home. There really wasn’t a sense of, maybe we can work together, maybe we can make this a more interesting department.

Science is not something you do in a bubble. You don’t just come up with a great result, publish a paper and become famous. I had a hard time finding people to collaborate with. Even in areas where I was considered the expert outside of Purdue, people there weren’t willing to listen to me.

Yet I kept telling myself, I can find a way to make this work. I am a problem solver. I eventually did make full professor. But of the two to three thousand faculty at Purdue, only 20 to 30 were Black. And only about 10 of us were full professors. That’s less than 1 percent. When I realized I was in such a small minority, that’s when I really did respect that it was very difficult to make it to that high of a rank. Ultimately, I realized that I had no reason to do this anymore. I had nothing more to prove.

What’s one of your biggest successes?

A big success for me today is being able to be back here in Los Angeles to help take care of my parents. That may sound a bit silly, but often we’re in a culture where people think a scientist or mathematician has to be the crazy person locked up in a room working by ourselves. I bought into that for a long time, thinking it doesn’t matter where you live or what kind of life you have — that all that’s important is doing the math.

But as I watched my parents get older, I realized it would be nice if I could be around to help them. Little things like taking them out to the movies, taking them to restaurants and amusement parks and other places. It’s comforting to know that, yes, I’m here at work. Yes, I’m teaching classes. Yes, I’m mentoring students. But when everything’s done, I can go home and spend time on weekends knowing I’m there to help my parents also have a good life.

How do you get your best ideas?

I think I get them by being an information junkie. I love to watch documentaries. I will turn on PBS. I will turn on the History Channel. I love science and discovery. Watching documentaries gives me ideas of how things work.

I also like attending conferences where I watch other mathematicians give presentations on their research. I don’t always understand what people are saying, but there’s always one equation they’ll show that gets me thinking, “Where did I see that before?” Then I start making connections and trying to figure out why they would use this equation here whereas others use it in a completely different context. What’s the relationship?

I try to get information anywhere and everywhere. And eventually I start seeing how these things are all related.

What do you do in your spare time?

I’m big into watching movies. Any kind of movie — small independent films, large blockbuster films. I get into conversations with my students about movies all the time. I think 1917 was one of the best movies in recent memory. I’m a big fan of the Avengers — the whole Marvel cinematic universe and the 20-some-odd movies that have come out over the last 10 years.

Also, there are things I did quite a bit when I was younger but haven’t really done the last 10 years. I’ve now gotten back into playing classical piano.

What piece of advice do you wish you had been given when you were younger?

Try to determine what your passion is — not necessarily something you’re good at, but something you really like.

This Q&A is part of a series exploring the many paths to a career in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). It has been made possible with generous support from Arconic Foundation.