High-speed lasers write data — to last millennia — inside glass

The data might outlast humanity, leaving messages for future civilizations — or even aliens

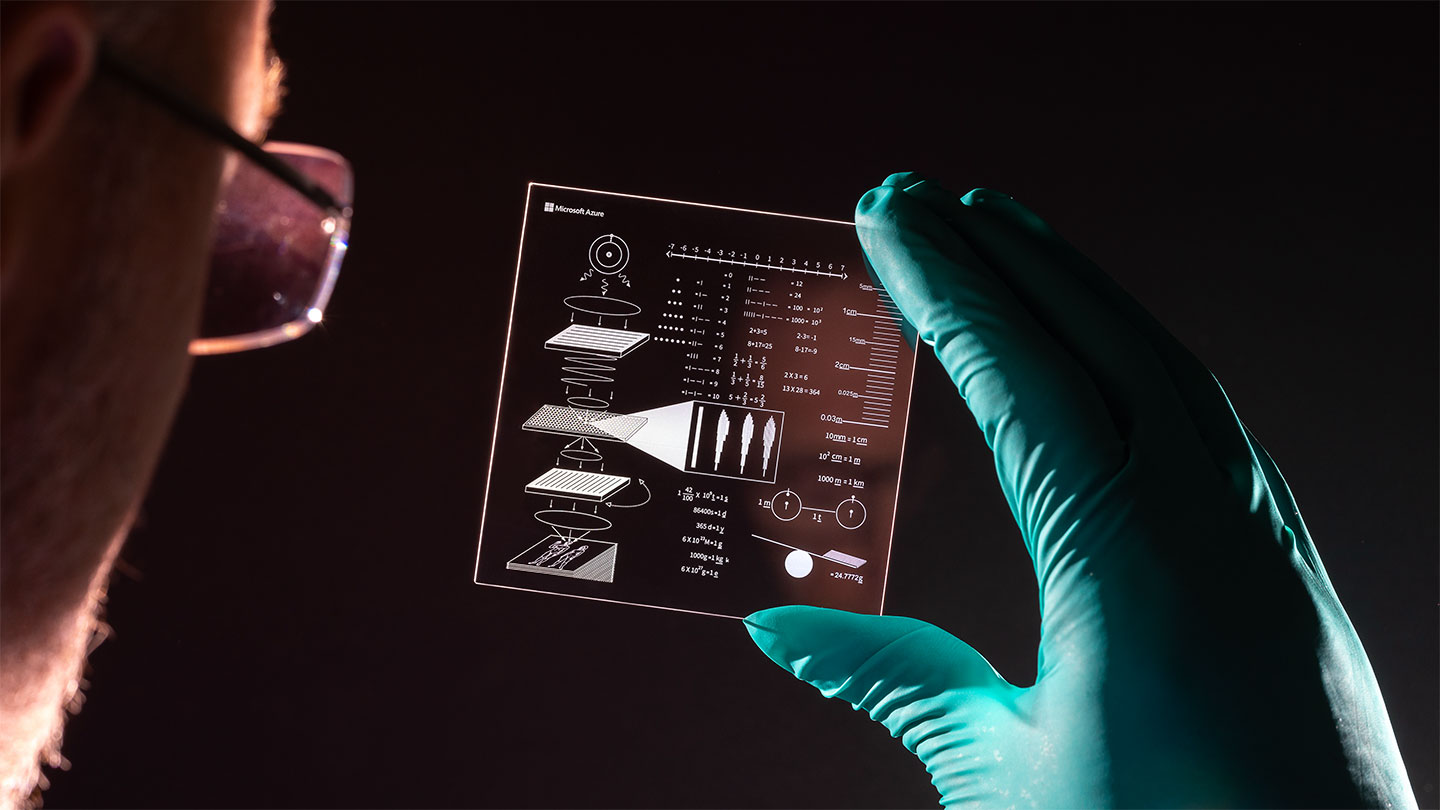

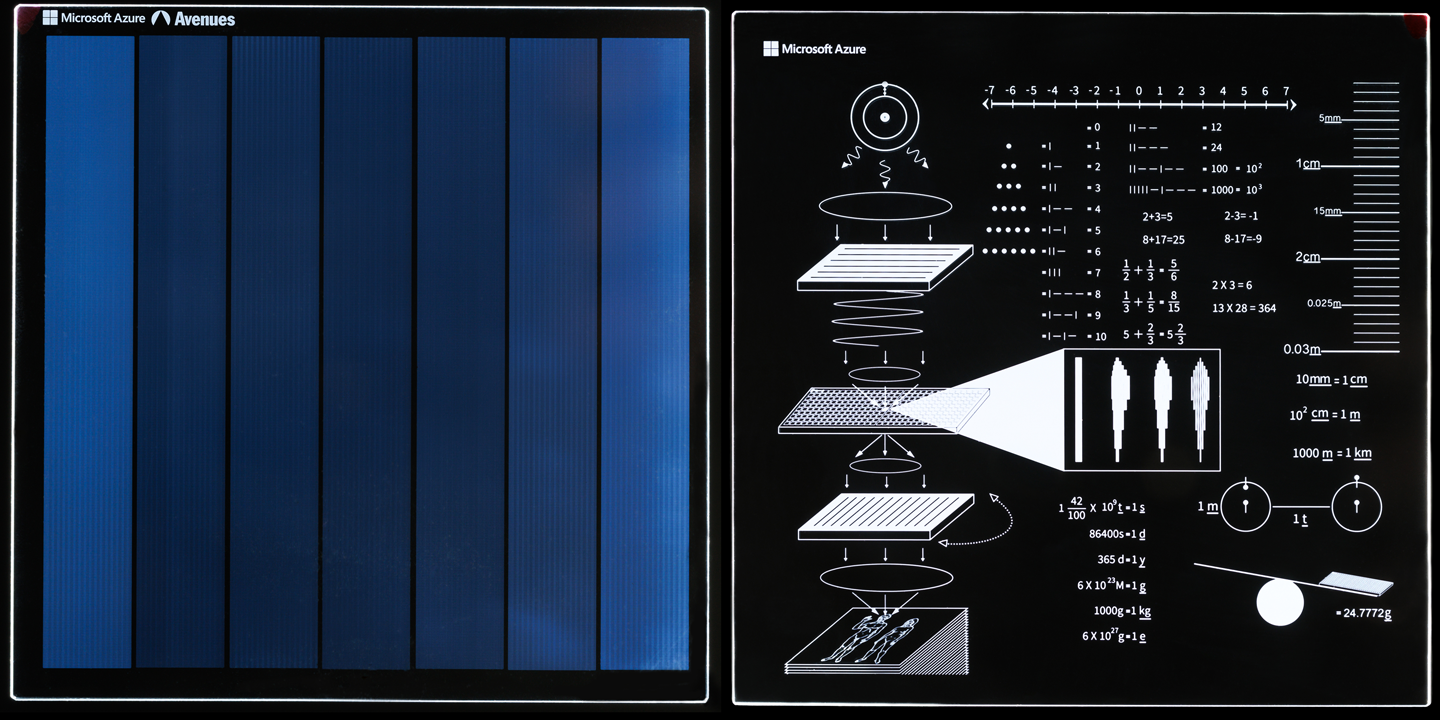

Richard Black (pictured) and his team at Microsoft Research are developing a new way to store data inside glass platters. High school students are using it to record a message to be sent into space. The drawings on this platter explain how to read the message, which will be stored on another platter.

Microsoft Research

A robot whirs along a library shelf. Instead of books, this shelf holds napkin-sized squares of flat, clear glass. The robot selects a piece of glass and brings it over to a microscope. The instrument peers deep inside the glass. A speckly pattern, invisible to the naked eye, now comes into focus. A high-speed laser etched this pattern. And a computer can now read the digital information stored within it.

Each piece of glass is like a book after all — a very futuristic one. Each slim plate can hold 7 terabytes of data. That’s as much information as two million books typically hold today.

The library, robot, laser, microscope and platters of glass are all part of a research program named Project Silica. Richard Black directs this project at Microsoft Research in Cambridge, England. “Project Silica is a new approach to storing data,” he says.

The latest computer hard drives easily hold terabytes worth of data. But those drives last only around three to five years. In fact, all of today’s common methods of storing digital data tend to wear out quickly, Black notes. “Every few years, you’ve got to buy a new [storage medium] and copy.” And then, over and over again, “buy and copy, and buy and copy.”

The speckly data inside the glass, though, can last for “thousands of years,” Black says, or perhaps even longer.

“It’s a very neat and clever idea,” says Deep Jariwala, who did not take part in this project. An electrical engineer, he works at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Glass is actually quite durable. These platters can withstand all sorts of calamities. “You could leave [the glass platter] in boiling water,” says Black. “You can put it in the oven. You can microwave it.” You could even scratch the surface without marring the data inside it.

Or you could jettison the glass platter into space, carrying a message to aliens. That’s exactly what an international team of high-school students plans to do. In a podcast last fall, Microsoft Research announced its support for this project, called Golden Record 2.0.

How to write inside glass

“It’s fun to think about talking to aliens,” says Jon Lomberg. He’s an artist based in Kona, Hawaii. But those glass platters may soon have important uses here on Earth. People create and use a staggering amount of information. There are medical data, scientific experiments, banking records, Hollywood movies and so much more.

A lot of this information “needs to be kept for a long time period,” Black said in the podcast. “There’s huge quantities of it. And it’s pouring in every day.”

Back in 2014, researchers at the University of Southampton, England, used lasers to record data inside glass for the first time. At the time, “we were very happy,” says Jingyu Zhang, who was part of that team. He’s now a physicist at Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan, China.

The laser pulses are so rapid that they are measured in femtoseconds. One femtosecond is one-thousandth of one-millionth of one-millionth of a second, Black explains. Taking even a small amount of energy and focusing it on a tiny point for such a teensy amount of time has surprising results. “The intensity at that point is just so mind-bogglingly high,” he says. “You get something called a plasma nano explosion.”

This explosion creates a very tiny divot in the structure of the glass. Engineers call it a voxel.

Voxel formation is predictable. Whenever you fire the laser the same way, the voxel forms the same way, Zhang explains. So different types of voxels can act like 1s and 0s to represent digital data. These voxels also can be layered on top of each other inside a sheet of glass. When you want to read the data, you use a microscope. It focuses on a small area of just one layer inside the glass. A camera records the pattern of voxels there.

In the decade since the discovery by Zhang’s team, Microsoft has been improving the technology. They’ve found ways to write and read voxels faster and more reliably. They also now use machine learning, a type of AI, to convert voxel patterns back into digital data. Plus, they’ve built a library of these stored sheets of data. It features robots called shuttles that shelve and retrieve glass platters.

So far, a robot has never yet dropped a platter. But if a platter broke or got lost, Black says, its data can always be found spread across many other platters. This is a common technique used when storing data on all kinds of media.

For now, this is the only library of its kind. But Black has big goals. Microsoft runs hundreds of data centers. “The goal,” Black says, “would be eventually [a library like this] is in every data center.”

For data that we want to work with or access regularly, we will still need regular hard drives. That’s because voxel patterns can’t be altered once they’re written. “This is an archival form of data storage,” says Jariwala. It’s meant to last a long time, unchanged. That’s why it’s such a perfect technology for the golden record project.

And being unchangeable makes the stored data essentially hack-proof, Black adds. That’s in sharp contrast to the magnetic tape used in past long-term storage methods. Tape can be rewritten as it’s being read.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

A message from humanity

The new golden record that’s being aimed at aliens is not the first of its kind.

Back in the 1970s, NASA launched two Voyager spacecraft. Their main goal was to explore the solar system and beyond. Each one also carried a 30-centimeter (12-inch) gold-plated copper disk. The disks contain a message about humanity. Jon Lomberg selected many images and much of the music stored on the records.

Such a disk is like “a message in a bottle thrown into the ocean,” he says. These spacecraft are still out there, flying through the depths of space. If aliens ever find one, they’ll be able to learn about who built it.

However, those records used a very early type of data storage. Not much fit onto a disk. Plus, humanity has changed a lot in the decades since. Alicia Zheng and Noe Mathew are working on the message for the new record. Both are juniors at Avenues The World School in New York City. “Ours is more of a modern version of the original,” says Alicia.

Students at schools in São Paulo, Brazil, and San Jose, Calif., are also involved in the project. Lomberg is advising all these students. But this time around, he’s not choosing what to put into the message. “I’ve had my chance to say what pictures should go and what music should go,” he says. He hopes lots of young people will contribute to the new message.

You can send in pictures or other suggested content to the Golden Record 2.0 website. “It can be photos of family. It can be pets. Pictures showing different cultures from around the world are also important,” says Alicia.

Noe points out that they are also looking for audio, including greetings in different languages. “We have to think about how to represent humanity as a whole,” Noe says.

The students haven’t yet found a spacecraft to carry the message. But they aren’t rushing. They want to take time to perfect the message first, says Lomberg.

A time capsule

We don’t yet know if life even exists beyond Earth. And the universe is a vast, mostly empty place. So chances are slim that another being will ever find one of these messages — either the older metal versions or the new ones made of glass.

However, even if the messages never get found, Lomberg and the students he’s working with think their efforts are worthwhile. “The fact that [the golden records] will be there long after humans are gone, perhaps long after the planet itself is gone, is awe-inspiring and thrilling,” says Lomberg.

Alicia says, “It’s not only an archive of humanity for aliens, it’s also an archive for us.”

Dexter Greene worked on the project with Alicia and Noe until he graduated last spring. He’s currently studying mechanical engineering at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. “I like to think of it as a time capsule of humanity,” he said in the podcast. “It is about showing who we are to ourselves. Like taking a step back to realize where we are, how far we’ve come, which direction we should go.”

This is one in a series presenting news on technology and innovation, made possible with generous support from the Lemelson Foundation.