Laundry tweaks can help clothes last longer and pollute less

Cooler water and a shorter wash cycle cut down on fading and fabric thinning

How you wash your laundry affects how long your favorite clothes last, as well as their impact on the environment.

KatarzynaBialasiewicz/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Did you ever notice how your favorite clothes lose their color and seem flimsier with time? Washing may be to blame. A new study has shown just how much the time and temperature of a wash cycle can affect clothing.

It found that clothes lose less dye and fewer fibers when washed in shorter cycles and in cool water. That means they will fade and thin less. These wash settings are greener, too — as in better for the environment.

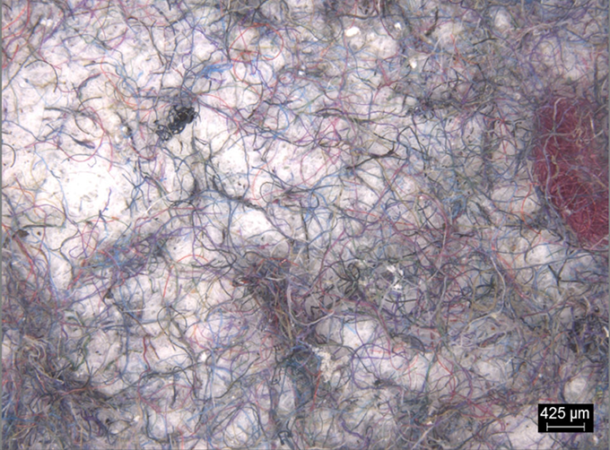

As clothes swish around in a washing machine, some of the fabric’s fibers loosen and wash away. Clothes also lose some of the dyes that had colored them. We may not notice a difference right away. But over time, clothes can turn dull. Fabrics can thin. The dyes and fibers lost in the wash water will end up in the environment.

“There is some sort of environmental impact to almost everything you do,” says Lucy Cotton in England. She is the study’s lead author. She worked on the project as a grad student at the University of Leeds. Her research team put together two batches of clothes to launder in tests. One had dark-colored t-shirts. The other had shirts in vibrant, lighter colors. Each load had various cotton and polyester fabrics. Their dyes and fibers were typical of the mix of clothes laundered at home.

The team also included in each wash load 18 swatches of white t-shirt fabric. Those white fabrics can absorb dyes lost in the wash from colored fabrics.

The team washed each type of load in the same machine. They used two different cycles. The “cold express” wash lasted 30 minutes and used 25° Celsius (77° Fahrenheit) water. The “cotton short” cycle used 40 °C (104 °F) water and ran for 85 minutes. After each cycle, the team collected fibers in the wash water and from an extra empty wash cycle afterward. (That extra cycle rinsed any leftover fibers out of the machine.) The team repeated the wash cycles and extra empty rinses 16 times for each load and cycle. The group then let the clothes air-dry for a full day.

Afterward, the team compared the t-shirts and white swatches to ones that had never been washed. They used an instrument called a spectrophotometer (SPEK-troh-foh-TOM-eh-tur) to gauge the color of each sample.

How laundry loads stacked up

All shirts lost more color when washed in hot water on the longer cycle. Cotton ones faded more than the polyester ones. The team also stirred swatches of the dark t-shirts in water at 20 °C (68 °F), 40 °C and 60 °C (140 °F). Room-temperature water released less dye than the hotter water did.

The shirts also lost more tiny fibers in the longer, hotter cycle. Those microfibers matter because they give fabric its heft and strength. Lose too much and the fabric will thin and weaken. Those microfibers also will pollute waterways.

Water from the long and hot wash and rinse cycles collected about 40 percent more fibers from the dark load compared to the cool express cycle. Lighter-colored clothes in the long, hot wash lost around 30 percent more. And the effect continued the more the clothes were washed. The team still found the hot, longer loads released at least 40 percent more microfibers than the cool cycles after eight or 16 washings.

“The duration of the wash cycle could be the most important factor,” says study co-author Richard Blackburn. As a chemist, he heads the Sustainable Materials Research Group at the University of Leeds. The longer the cycle, the more the fabric is shaken and rubbed against other fabrics. The fabric also sits in water longer. But temperature matters, too. Hotter water can make fabric fibers swell. And that can make fibers more likely to break, he adds.

The team published its findings in the June 2020 issue of Dyes and Pigments.

“This is a well-designed study,” says Mourad Krifa. He’s an industrial engineer who studies textiles and clothing. He works at Kent State University’s School of Fashion Design in Ohio. The new study, he adds, “clearly shows” that color and fiber loss in the wash “increase with cycle duration and temperature.” He would like to see follow-up work that looks into whether these factors affect other types of fabrics in the same way.

Greening our cleaning

“Nobody wants to wear a t-shirt that doesn’t look as good as when you first bought it,” says Blackburn at Leeds. With that in mind, it makes sense to wash clothes in cooler, shorter cycles, he says. Your shirts will still get clean. Modern detergents are made to work in cooler, shorter cycles, he explains.

A shorter, cooler wash cycle also is easier on the environment. First, it cuts down on energy use. Electricity from fossil fuels adds to greenhouse-gas emissions, which drive human-caused climate change. Using less energy saves money, as well.

Shorter, cooler wash cycles also cut water pollution. Dyes can contain hazardous chemicals. And all of those lost fibers add up. Those shed in a typical wash load make up a wad about “the size of a chewing gum,” says Flávia Salvador Cesa. She’s a graduate student at the University of São Paulo in Brazil.

Cesa was part of a research team that estimated the loss of fabric fibers each year due to washing machines across the globe. The total comes to about 18,300 metric tons (21,200 U.S. short tons) of cotton and 12,500 metric tons (13,800 U.S. tons) of synthetic fibers. The team looked at prewashing of fabrics by manufacturers. It also looked at how the use of detergents or better filters on consumers’ washing machines might help. A combination of those measures might cut the total fiber loss by about half, her group now reports. Yet many tons still would wash away into waterways.

The team shared its findings in the February Environmental Pollution.

Fibers lost in the wash can wind up in oceans, lakes and streams. Those fibers make up about one-third of all microplastics in waterways. That’s the estimate of a 2017 report by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

But it isn’t just a plastics problem. Spanish and British researchers studied microfibers in a deep area of the Mediterranean Sea. About eight in every 10 were cotton and linen. That study was published in 2018. “Even though it’s cotton and it’s a natural fiber, it’s clearly not degrading in that marine environment,” Blackburn notes. He and other scientists are trying to learn why. Other scientists are studying the effects of these polluting fibers on sea life.

Cesa likes that the shorter, cooler wash cycles suggested by Cotton’s group can provide many benefits — from less pollution and lower consumer costs to better-looking clothes.

And, just as little wads of microfibers add up to tons of waste, even small steps to cut waste will also add up. “Everything that you can do can make a difference,” Cotton says, “even if it is something as simple as changing your wash settings.”