Let’s learn about Pluto

Pluto is the most famous dwarf planet in our solar system

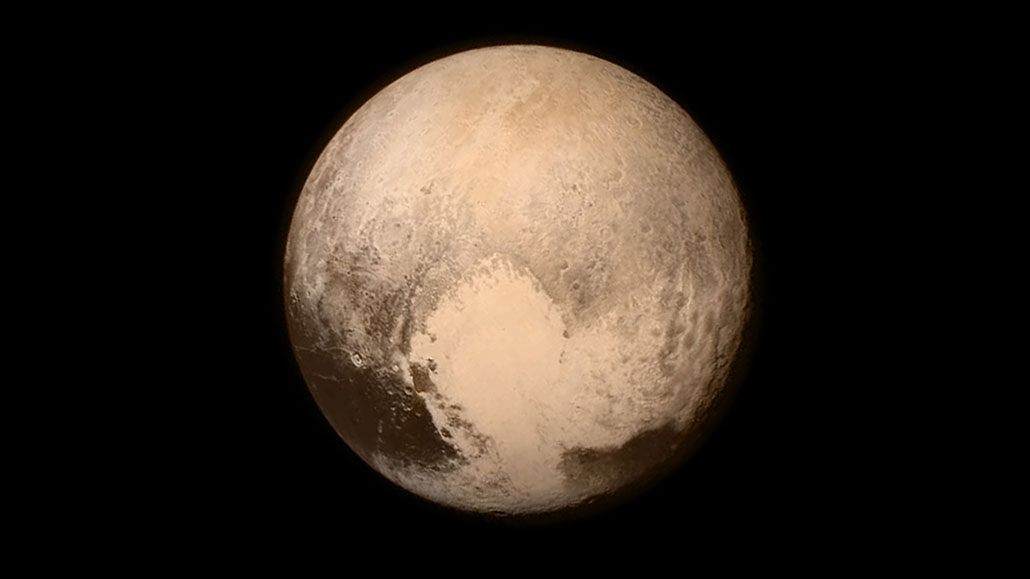

When New Horizons zipped by Pluto in 2015, the spacecraft transformed our view of the dwarf planet from a speck in the sky to a richly complex world.

NASA/APL/SwRI

For such a small world, Pluto has stirred up a pretty big controversy. Discovered in 1930 by amateur astronomer Clyde Tombaugh, Pluto was long known as the solar system’s ninth planet. But in 2006, an international group of astronomers came up with a new definition of the word “planet.” And Pluto didn’t make the cut.

The new definition required a planet to do three things. First, it must orbit the sun. Second, it must have enough gravity to mold itself into a round shape. Third, it must have enough gravity to clear its orbit of other objects. Pluto didn’t meet the third requirement. It orbits the sun in a ring of icy bodies beyond Neptune called the Kuiper Belt. So, Pluto was demoted to “dwarf planet.”

More than a decade later, some scientists still disagree with that decision. A world should not have to sweep debris out of its orbit to count as a planet, they argue. Plus, the word “planet” has been redefined many times. There is no reason that the 2006 definition should be the final word, they say.

Planet or not, one thing is certain about Pluto: It is just as fascinating a place as Mars, Jupiter or any other member of the planetary club. And it’s very different from those other orbs. Pluto’s orbit, for instance, isn’t circular, and it doesn’t occur on the same plane as the big planets. Its tilted, oval-shaped path takes it above and below the orbits of the other planets. And while Pluto sits an average 5.8 billion kilometers (3.6 billion miles) from the sun, sometimes it approaches closer than Neptune.

Pluto and its five moons are so far away that they take nearly 250 Earth years to loop around the sun once. And since Pluto is so far from the sun’s warming rays, temperatures hover around –230 °Celsius (–380 °Fahrenheit).

Pluto is tiny. At about 2,380 kilometers (1,400 miles) wide, it is only half the width of the United States. But the dwarf planet’s surface features were largely a mystery until NASA’s New Horizons mission flew by in 2015. That spacecraft was the first to view Pluto up close. The spacecraft’s observations unveiled Pluto’s famous heart-shaped glacier. New Horizons also revealed Pluto’s dunes of methane ice and a gash in the planet twice as deep as the Grand Canyon. These features and others make up Pluto’s richly varied topography — another reason some scientists say Pluto should count as a planet.

Even as the debate over Pluto’s planetary status rages on, some sky watchers seek a new ninth planet. This would be a planet about 10 times as massive as Earth, lurking on the fringes of the solar system. The motions of some icy bodies in the Kuiper belt have hinted at the existence of such a planet, known as Planet Nine or Planet X. Other recent evidence suggests it does not exist. But for many researchers and citizen scientists, the hunt is on.

Want to know more? We’ve got some stories to get you started:

Pluto is no longer a planet — or is it? Some astronomers did not agree with Pluto’s 2006 demotion and even now call it a planet (10/28/2021) Readability: 7.4

Pluto’s heart has dunes of methane ice Pluto’s heart-shaped plains are striped with sand dunes. The sand is made of methane ice.(7/5/2018) Readability: 7.0

Cool Jobs: Probing Pluto The New Horizons mission captivated the world as it flew by Pluto in 2015. Here are some of the scientists and engineers who made it possible. (2/16/2017) Readability: 7.1

Explore more

Let’s learn about space robots

Students send instrument to Pluto

New Horizons data reveal first global maps of Pluto and Charon

Weird Pluto gives up its secrets

Activities

Want to be the next Clyde Tombaugh? You too could potentially discover a new world lurking on the edge of our solar system. Backyard Worlds: Planet 9 is a citizen-science effort to search the realm beyond Neptune for planets and brown dwarfs. (Brown dwarfs are balls of gas that are too big to be called planets but too small to be stars.) Volunteers scour pictures taken by NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer mission for such hard-to-spot objects.