Particles from tree waste could prevent fogged lenses, windshields

Coating glass with water-loving nanoparticles can keep droplets from clouding the view

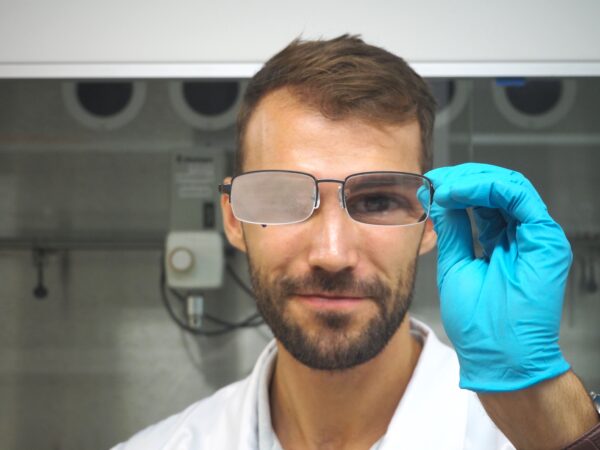

Coming in from the cold or cooking can fog up lenses, making it difficult to see. For example, when cooking pasta, some of the water turns into steam. When that hot steam hits a cooler surface, such as a pair of eyeglasses, water droplets form on the lenses.

milanvirijevic/E+/Getty Images

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

Cold winters can be extra annoying for people who wear eyeglasses. Practically every time they come indoors their lenses get fogged up. The same thing happens when the warm air from a car’s heater hits a cold windshield. A new coating could prevent that fog. Its key ingredient: tiny particles made from tree wastes.

When you enter a house from the frosty outdoors, the warm air around you cools. This causes some of the water vapor in the air to condense out into droplets. If you have glasses, nearby water droplets will latch onto the lenses and fog them up, explains Alexander Henn. He developed the new coating at Aalto University in Espoo, Finland.

The shape of the water drops that glom onto glasses is what makes it hard to see, says Monika Österberg. A chemist, she also works at Aalto University. Droplets scatter light in all directions, she says. Look through them and you can’t focus on anything. But look through a thin film of water and all is clear.

Österberg and Henn tackled the fog challenge using a renewable waste product — lignin. It’s a polymer — a big molecule made from smaller building blocks. Woody plants contain lots of lignin. That’s what keeps them stiff and strong.

“Here in Finland, we have a lot of trees,” Österberg says. “Everyone knows that you can build with the wood. Or you can make pulp that you can use to make paper or, now, textiles,” she says. But most of those processes don’t use a tree’s lignin. It ends up as a waste product.

Waste lignin is a brown powder that looks a bit like cocoa. It can be burned as a fuel. But there are more valuable and environmentally friendly ways to use it, Henn says.

Scientists are exploring new ways to use this abundant resource.

There are two main approaches, says Bin Yang, who did not take part in the new work. But this chemical engineer and microbiologist at Washington State University in Richland is familiar with such tactics. He works on tech to develop energy from renewable resources. The first approach, he explains, is to make new chemicals and fuels with lignin. The second is to make new materials such as nanoparticles. Nano bits are so small that they’re measured in billionths of a meter.

The researchers were working with lignin nanoparticles before they started thinking about fog. To make them, the scientists dissolved lignin powder in a liquid made of organic molecules (ones with a carbon backbone). When they poured that liquid into water, the lignin bunched up. It formed tiny clusters dispersed in the water. Each one was about 100 nanometers in size. Those tiny bits were hydrophilic, which means they loved water, Henn says.

Cutting the fog

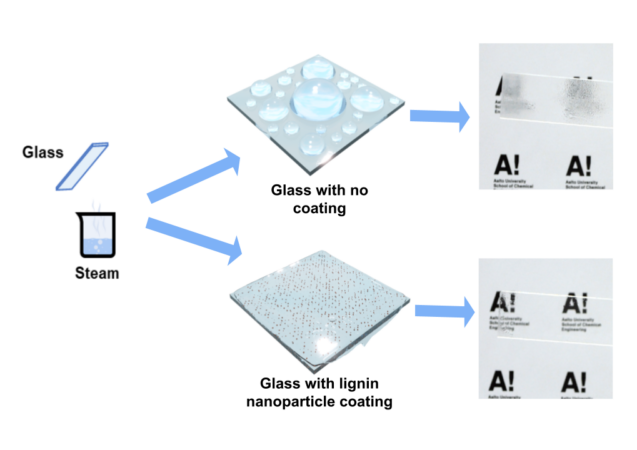

Henn realized that coating glass with water-loving lignin bits would change how its surface interacts with water. The nanoparticles want to grab onto the water. That would make them spread out across the glass surface. If that water spreads out enough, the droplets would form a continuous thin layer. Now wet, the lenses might not be foggy.

There was just one problem. “You could see the particles,” Henn says. So putting lignin bits on glass would make it look a bit dirty.

This motivated Henn to make smaller lignin particles. He swapped a group of atoms on the lignin polymers for one that interacts differently with water. This made the polymers bunch up extra tightly. They formed particles smaller than 50 nanometers across — tiny enough to escape notice.

They coated glass with a single layer of this lignin liquid. And it kept the glass from fogging up in steam and during temperature changes. The group shared its finding November 1 in Chemical Engineering Journal.

“Lignin can do many, many different things,” says Yang. Here, it creates a super water-loving surface where water cannot form droplets, he says. But it could also be used for making renewable fuels. It also absorbs light in interesting ways. Lignin is the second most abundant biomaterial produced by photosynthesis, Yang notes. It’s just an incredible renewable resource, he says.

The coating isn’t costly and scaling up its production should be easy, the researchers say. And the coating could do more than make life less annoying for glasses wearers — it could make life safer, too. Many people whose work calls for eye protection don’t wear safety glasses because clearing foggy lenses slows down the work, says Henn. Lignin could offer a sustainable solution.