Loneliness can breed disease

Lacking strong ties to friends and family can pose a serious risk to health

Teens are particularly susceptible to loneliness. But there are important health reasons to try and overcome it.

Shadrin Andrey/iStockphoto

By Hugh Westrup

Feeling homesick, alone in a crowd or rejected after being chosen last for a team? Everyone now and then experiences a pang of loneliness. It’s painful, but not because we’re wimps. Loneliness can actually cause very real harm, research is showing.

Like elephants, honeybees and flamingos, we are social animals, explains John Cacioppo. A psychologist at the University of Chicago, he studies human behavior. People survive and flourish only in groups, his team and others have found. Loneliness, Cacioppo says, reminds us that people didn’t evolve to go it alone.

The human need to socialize — to spend time with companions — has deep roots, he explains. And they go back a long, long way.

Studies of modern hunter-gatherers, such as the !Kung San, reveal what life may have been like for prehistoric humans. (The exclamation mark in !Kung symbolizes a clicking sound. It’s made by pressing the tip of the tongue against the roof of the mouth.)

The !Kung San live in southern Africa. Their communities are very close-knit. They share all food. !Kung mothers keep their babies in constant close contact. Such a tight-knit community would have saved prehistoric humans from harm. It protected them just as it protects the !Kung today from the harsh environment of the Kalahari Desert.

But few of us live as hunter-gatherers today. Advances in science and technology have transformed human cultures over the centuries, Cacioppo observes. Most of us no longer need to huddle together to survive the elements. Still, he contends, we all share with our earliest ancestors the same basic need to socialize.

What our ancestors didn’t share was our growing understanding of the threats loneliness can pose. A persistent lack of company — chronic loneliness — can weaken our ability to look after ourselves, recent research shows. In some cases, loneliness can even turn the body against itself. Social relations, says Cacioppo, are vital to human well-being in ways that researchers are just coming to understand.

The message that’s emerging from the new data: Persistent loneliness may turn out to be as harmful to our health as cigarettes, alcohol or obesity. Fortunately, the opposite is also true. Says Cacioppo: “Strong connections to family and friends help keep us healthy.”

Starved for companions

Loneliness becomes a serious risk to mental and physical well-being when it lasts a long time. Lengthy social isolation can leave people starved for intimacy. Intimacy is the closeness and warmth of personal relationships.

It’s natural for people to seek out others with whom we can share our thoughts and feelings. We all want others to accept us for who we are. Yet one in four adults taking part in a U.S. survey 10 years ago reported having no one to confide in.

And loneliness doesn’t just affect adults. A 1998 survey of U.S. 15-year-olds found that loneliness troubled them too. Fifteen percent of the boys surveyed and 19 percent of the girls reported feeling lonely often.

Chronic loneliness is a common experience for those who feel like they’re social outsiders. This group tends to include people who are old, poor, bullied or face discrimination.

Three decades ago, few people felt more outside the social mainstream than did gay men. Attitudes toward homosexuality were narrower then. So most gay men lived partly or wholly “in the closet.” These men hid the fact that they were gay from friends, coworkers and family members. Meanwhile, an AIDS epidemic killed tens of thousands of homosexual men during the 1980s. It intensified the fear that being exposed as gay would increase the risk of being socially excluded.

During the 1980s, researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles conducted a long-term study of more than 80 gay men. Many participants were infected with HIV. This is the virus that causes AIDS.

Combing through data from the study, a young researcher named Steven Cole made a remarkable discovery. Men who were in the closet died of AIDS two to three years sooner than those who were openly gay. The loneliness brought on by keeping one’s homosexuality a secret sped the progression of AIDS, Cole concluded.

In 2010, Julianne Holt-Lunstad expanded upon Cole’s findings. Holt-Lunstad is a psychologist at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah. She analyzed 148 studies published over the past century. Together, these studies had gathered detailed data about the social lives and health of more than 300,000 men, women and children.

People with strong ties to family, friends and co-workers were only half as likely to die over a 7.5-year period as were people with few social connections, Holt-Lunstad’s analysis showed. She published her findings in the journal PLOS Medicine.

“Weak social ties have the same negative effects on health as alcoholism or smoking 15 cigarettes day,” Holt-Lunstad found. “Having a weak social network is twice as risky as being obese.”

Out of control

Experts have different explanations for why a weak social network would shorten human life. Some think a lack of caring friends and family may reduce the odds of getting help during medical emergencies. Others have uncovered signs of more complex reasons.

Healthful habits all rely on self-control. These habits include exercising regularly, eating sensibly, and drinking alcohol in moderation. Psychologists refer to this as “executive” control.

The frontal lobes of the brain regulate executive control. Located right behind the forehead, the frontal lobes are nerve cells that work as a team. They rein in our desires, emotions and behaviors.

As we grow and develop, executive control evolves. Babies demand instant gratification. They want what they need now. By the teen years, we learn to restrain those impulses. We pay attention in class. We save for the future. And we look after our bodies. The brain’s executive-control center manages all of this.

Lab experiments conducted between 2000 and 2005 by Roy Baumeister found that loneliness impairs executive control. Baumeister is a psychologist at Florida State University in Tallahassee. His experiments showed that even imagining loneliness had this effect. After Baumeister convinced young people who weren’t lonely that they were destined for a lonesome existence, they performed poorly on tests of executive control.

Loneliness also seems to slowly chip away at healthy behavior over the years, explains Cacioppo. The young people who were socially isolated in his research still led healthy lifestyles, despite their loneliness. They ate sensibly. They exercised frequently. But as people got older, that changed. Lonely adults who were middle-aged or older showed less restraint. They ate fattier foods than their peers did. They exercised less, too. And they consumed more alcohol. Giving in to such bad habits may be one reason why lonely people die much earlier in life, Cacioppo now concludes.

Stress responses

The health impact of loneliness does not end with eroding willpower. “It reaches into the body’s cells and tinkers with their DNA,” explains Cole.

Hormones are chemicals the body produces. They control many important activities, including growth and sexual development. The body unleashes stress hormones as part of its response to perceived threats. Any scare can activate the nervous system. That, in turn, provokes the release of a flood of hormones. That flood girds the body for action. The hormones make the heart beat faster. They raise blood pressure. They can even cause muscles to clench.

The stress response is a survival mechanism inherited from our ancestors. They needed it to survive in a world where enemies and predators were commonplace. Today it still prepares people to confront bullies or escape snarling dogs.

But often, it isn’t a threat to our physical safety that now triggers a stress reaction. Instead, it’s the threat posed by the emotional pressures of modern life.

“Most of our stress responses are set off by non-injurious threats,” Cole says. “Those threats might be worries about the future or unemployment or social isolation.”

In fact, chronically lonely people, Cole says, have higher levels of stress hormones. Those hormones include cortisol and epinephrine (Ep uh NEF rin). Epinephrine is also called adrenaline.

Frequent stress isn’t healthy, Cole notes. The high levels of stress hormones seen in lonely people affect more than their heart and muscles. Stress hormones also activate the immune system. They provoke what is known as inflammation.

It’s something you’re probably familiar with if you have ever cut a finger or stubbed a toe. The injured tissue becomes inflamed. In other words, it swells up and turns red. Those symptoms indicate that the immune system has dispatched cells to the injury site. Their goal: to destroy any potentially harmful viruses or bacteria that may have invaded it.

Changes in immunity

In 2007, Cole discovered that the genes that turn on inflammation are unusually active in lonely people. Their immune systems appear to be working overtime, as if preparing their bodies for invaders that do not exist.

That’s disturbing, Cole says, because persistent inflammation can be harmful. It underlies many unhealthy conditions. Diabetes, heart disease and the dementia associated with Alzheimer’s are among those conditions.

The concern is that loneliness may shorten a person’s lifespan by shifting the immune system into long-term overdrive, his research suggests.

In a recent and related study, Cole and Cacioppo found that the immune systems of lonely people were different in another way. They were primed especially to fight infections caused by bacteria. But not by viruses.

That lopsided readiness for action may pose a further threat to lonely people, says Cole. The body isn’t good at switching from fighting bacteria to combating viruses (or the reverse). For instance, people might die from a bacterial illness, such as pneumonia, soon after successfully recovering from the flu or some other viral disease. Being able to switch from fighting viruses to bacteria (or vice versa) is even more difficult if the immune system is over-prepared to combat one or the other, says Cole. That appears to be true for lonely people.

Cole also has been looking at the impact of loneliness on genes that control processes other than immunity. In one 2008 study, he worked with Susan Lutgendorf. She’s a psychologist at the University of Iowa. They examined the genes of women who had cancer of the ovaries. Some 220 genes were unusually active in women who had little or no support from family and friends, they found. Among those active genes were ones that make cancer more likely to spread throughout the body. The two experts described their findings in the journal Brain, Behavior, and Immunity.

Changing your expectations

During the last three years, Cacioppo has teamed up with psychologist Louise Hawkley. They have developed classes that help people overcome unhealthy loneliness. The lessons they offer aim to correct the faulty way that lonely people process information about others, says Hawkley.

“The classes challenge people to rethink the role they play in their social interactions,” says Hawkley. She works at the National Opinion Research Center in Chicago. There she conducts research on the effects of social relationships on physical and mental health.

Lonely people are like a !Kung tribe member lost in the African desert. Their thought processes switch into a self-preservation mode. Research shows that the minds of lonely people are on high alert. They are always scouting for the smallest sign of danger. When they engage with others, lonely people focus on negative comments or possibilities. They often ignore positive statements or scenarios.

In other words, says Hawkley, lonely people hear criticisms, not compliments. This can put them on the defensive. It also can make them ever more hostile. Such attitudes may drive others away, increasing a lonely person’s isolation, she says.

“Other people tend to behave the way we expect them to,” Hawkley says. “So why not expect the positive instead of the negative?” Doing that, she says, “might bring out what’s good in others.”

Yet Hawkley concedes that doing this isn’t easy: “Changing your expectations can be tough. It’s especially so when you feel lonely — when you think you’re the victim of everyone else’s negativity and there’s nothing you can do about it.” Still, she adds, “With practice, new ways of thinking can draw us closer to others.”

The outcome of that mental reset may lead to stronger ties to family and friends. It also may lead to more years in which to enjoy their company in health and happiness.

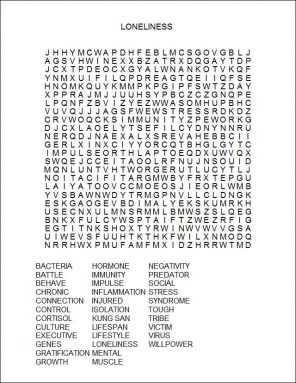

Power Words

acute severe but lasting for a short period of time.

AIDS(short for acquired immune deficiency syndrome) A severe disease in which the immune system is attacked and weakened, making the body susceptible to other infections. The virus is transmitted through bodily fluids, such as semen and blood.

Alzheimer’s disease A brain disease that can cause confusion, mood changes and problems with memory, language, behavior and problem solving. No cause or cure is known.

chronic Persisting over a long time.

DNA(short for deoxyribonucleic acid) A long, spiral-shaped molecule inside most living cells that carries genetic instructions. In all living things, from plants and animals to microbes, these instructions tell cells which molecules to make.

executive control The capacity to rein in one’s desires, emotions and behaviors. Executive control is regulated by the frontal lobes of the brain.

frontal lobe An area located at the front of each of the brain’s two hemispheres. Among other things, the frontal lobes are involved in recognizing the consequences of one’s actions, choosing between good and bad behavior, and overriding socially unacceptable impulses.

gene A segment of DNA that codes, or holds instructions, for producing a protein. Offspring inherit genes from their parents. Genes influence how an organism looks and behaves.

HIV (short for human immunodeficiency virus) A potentially deadly virus that attacks cells in the body’s immune system and causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, or AIDS.

hormone A chemical produced in a gland and then carried in the bloodstream to another part of the body. Hormones control important body activities, such as growth. Hormones act by triggering or regulating chemical reactions in the body.

hunter-gatherer A culture in which people hunt animals and harvest wild plants to eat, instead of growing crops and raising animals.

immune system The collection of cells and their responses that help fight off infection.

inflammation The body’s response to cellular injury, often involving swelling, redness, heat and pain.

!Kung San Tribes of hunter-gatherers who live in southern Africa, particularly the Kalahari Desert.

ovary A reproductive organ in female vertebrate animals.

psychology The study of the human mind, especially in relation to actions and behavior.

social isolation Feeling cut off from warm, supportive relations with friends and family.

stress (in biology) A factor, such as unusual temperatures, moisture or pollution, that affects the health of a species or ecosystem.

type 2 diabetes A disease marked by abnormal levels of sugar in the blood, caused by the body’s inability to use the hormone insulin properly. If untreated, it can cause heart disease, poor wound healing and nerve damage.