A louse-y start for clothing

A date for appearance of body lice suggests time of first clothes.

By Stephen Ornes

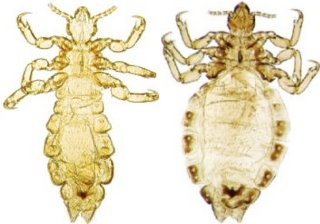

Lice are tiny and itchy, and they feast on human blood. So it’s hard to imagine that these insects could be useful. Head lice, which can grow to be about the size of a sesame seed, live on the head. Body lice live in clothing. These two types of lice are similar but not identical, and the difference between them may help explain something about humans.

In a recent study, scientists used a genetic study of head and body lice to estimate when people started wearing clothes.

Body lice and head lice have a common ancestor, which means that if you were to travel back far enough in time and study lice, you wouldn’t find both body lice and head lice — only head lice. At some point in the distant past, there was a split. Some head lice stayed head lice; others started to change in microscopic ways and set the stage for later generations to became body lice.

|

|

One type of human louse (left) lives on the scalp, and the other (right) lives on clothes. |

| SNK archives; S. Tuepke/Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology |

According to the recent study, body lice first appeared about 190,000 years ago. Some researchers have long suspected body lice, which live in the folds of clothing, appeared shortly after people started wearing clothes. So, the researchers propose, people probably started wearing clothes about 190,000 years ago, since it wasn’t long before the body lice moved in.

Before this study, scientists estimated that people started wearing clothes somewhere between 40,000 and 1 million years ago — a pretty wide range.

The changes that made body lice possible happened in the DNA of the lice. Inside almost any cell of a living organism is DNA, or deoxyribonucleic acid, the biological structure holding the instructions for life. DNA looks like a spiral staircase, where the supports are made of one type of chemical compound and the rungs are made of another.

These “instructions” are written in DNA. Carrying out the instructions for life are genes, which contain DNA. Every time lice — or any living thing — reproduce, the offspring’s genes are slightly different from the parents’. These changes are called mutations, and mutations make evolution possible. Over time, these mutations build up, eventually causing existing organisms — like some head lice long ago — to change enough to become new organisms — like body lice. In the new study, the scientists looked at DNA both in the nuclei of louse cells and in the mitochondria, which are the energy factories inside cells.

Andrew Kitchen, a scientist at Pennsylvania State University in University Park, led the new study. Speaking to Science News, Kitchen said that, with this new evidence, scientists can begin to understand how early humans were able to live in northern regions, which are cold — and would have required clothing.

If the new study is correct, then body lice as we know them today are only a little younger than Homo sapiens — which is the scientific name for human beings. The first Homo sapiens showed up about 200,000 years ago.

Of course, the new study makes lice more interesting — but not any less itchy or disgusting. So for the time being, let’s just leave the lice in the laboratory.

Going Deeper:

Bower, Bruce. 2010. “Lice hang ancient date on first clothes,” Science News, May 8. Available at http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/58435/title/Lice_hang_ancient_date_on_first_clothes

McDonagh, S. 2003. “Of lice and old clothes,” Science News for Kids, Aug. 27, Available at http://www.sciencenewsforkids.org/articles/20030827/Note3.asp