Lying won’t stretch your nose, but it will steal some brainpower

Even little fibs can have serious consequences — and some of them just might surprise you

Like Pinocchio, everyone sometimes tells a lie. Most people don’t lie often, science finds. But research shows that even small lies can take a toll on your brain.

malerapaso / Getty Images

I can’t come to your party because I have to help clean out the garage.

Your new haircut looks great!

I’ll do my homework before playing video games. Promise!

Lies, all of them.

Most of us have told a lie at one time or another. Some lies are harmful. Others — like the ones above — are mostly harmless. Still other lies, such as those used to protect other people, may even be created with the best of intentions. But no matter what kind of lie you tell, it takes a surprising amount of brainpower to pull it off.

Using up that brainpower can be costly. The brain drain it causes just might prevent you from performing some task or skill that’s important to you. And, of course, lying can have unwanted social impacts, too.

Mostly harmless

People lie for different reasons. Sometimes they do it to make themselves look better. Sometimes they lie to get out of trouble. Often, people will tell a fib to keep from hurting another’s feelings.

Overall, most people don’t lie very much, says Timothy Levine. He’s a psychologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Levine studies deception. And he’s done a lot of research on when and how much people lie.

Most people value honesty and want to be truthful, his research has shown. In one of Levine’s studies, almost three quarters of people rarely lied. And of all the lies reported in the study, 90 percent were “white lies.” It makes sense that many people value honesty. If you’re an honest person, people will trust you more. And trust is important. “By being honest with people, you build up social capital,” Levine says. Social capital is goodwill among people in a group or community.

However, Levine’s research also shows that while most people don’t lie often, a few lie a lot. The top one percent of liars, according to Levine’s research, tell more than 15 lies per day. Some chronic liars are insecure. Others may lie about their accomplishments because they’re conceited or overly impressed with themselves. Still others lie to take advantage of people — perhaps even to cheat them or to steal from them.

Some lies are well-intended. You know those small lies you might tell to make someone feel good? Scientists call them “prosocial lies.” Maybe you tell your parents that you loved the sweater they gave you for your birthday (even though you were really hoping for a new video-game console). That’s a prosocial lie. There’s little risk to you in telling it, and it makes your parents feel good.

Still, there are times that ones told to benefit others may cause the liar great harm. These are known as altruistic (Aul-tru-IS-tik) lies. During the Holocaust, some people told such lies to the Nazis about where Jews were hiding. The liars knew they could be killed if their falsehoods were discovered, but they took this risk in hopes of saving others. Clearly, some prosocial lies can be quite risky.

Hard work

When you tell the truth, your brain doesn’t have to do anything out of the ordinary. You think of what you want to say, and you say it. Lying takes much more work.

Here’s an example of what goes into a seemingly simple lie. Imagine you’re late to class and the teacher asks why and you decide to lie. You now have to either come up with a story on the spot or remember the story you made up as you were rushing to class.

So you say: “I had to stop by the library and pick up a book.”

Your teacher asks: “The book I assigned last week?”

Immediately, you must decide how to respond — and quickly. If you say yes, the teacher might ask to see the book. Or she might expect you to read from it in class. So, you have to imagine these possibilities. So you might say: “No. It was a different book.”

Now you have to be ready with another title in case the teacher asks which book you checked out. And you have to make sure it’s a book the school library actually owns. You’re only two sentences into the lie, and already you’ve been a) scrambling to make up a story; b) thinking about the various directions the conversation might take; and c) figuring out what you need to say to keep this whole lie from falling apart.

You might not be aware of it, but you just gave your brain a ton of extra work. It would have been far easier just to have told the truth: “I was talking to some friends outside the gym and lost track of the time.”

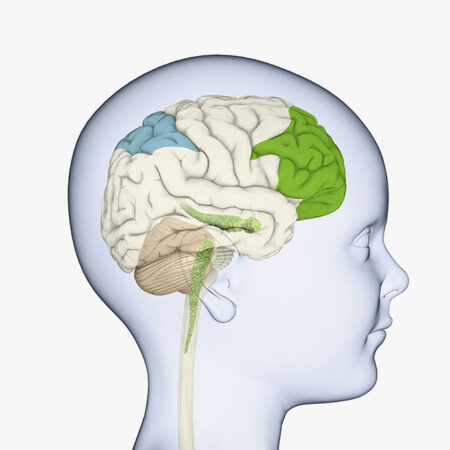

A lot of that brain work is done in a region called the prefrontal cortex. It’s the part in charge of working memory, explains Jennifer Vendemia. She’s a neuroscientist at the University of South Carolina, in Columbia. Working memory keeps something in mind just for a little while — such as remembering instructions for how to play a game or some other specific task. It’s a bit like your computer’s clipboard. It stores things for only a short while as you’re using them. It doesn’t put them in long-term storage. Besides working memory, the prefrontal cortex also takes care of tasks such as planning, problem-solving and self-control.

Scientists describe these as “executive function” tasks. Executive function comes into play when you use self-control to keep from blurting out the truth or some fact that would expose your lie. It helps you recall all the details of a lie to make sure that it sounds believable and you don’t slip up. Executive function lets you think a step or two ahead to make sure the lie you’re telling will likely hold up to questioning.

Calling on your executive function this way also uses up a lot of brainpower. One 2015 study done by researchers in Belgium found that the brain is slower and more likely to make mistakes when it shifts between lying and truth-telling. Vendemia’s research has also shown that someone’s mental workload will be heavier and their reaction time longer when lying.

Expensive lies

Spending so much brainpower trying to keep a story straight means there’s less available for other things — like solving math problems or remembering who invented the printing press. Lying is especially hard for young people, says Vendemia. The prefrontal cortex is not fully developed until around age 25. So younger people have fewer resources there to begin with. When the prefrontal cortex is busy with tasks related to lying, she notes, it now has a harder time doing other tasks that require planning, self-control or working memory. Those things might include planning a study schedule or using self-control to keep from drinking too much soda.

Lying to avoid getting into trouble — for being late to class, say — is pretty much a one-and-done. You’re not going to have to keep up that lie about going to the library for very long. Yes, you wasted some mental resources, but just that one time. Some lies, however, never stop. These are what Vendemia calls “lifespan lies.”

Spies, for instance, spend their entire lives lying about who they are. Someone with a difficult home life might lie to keep others from finding out — and that lie could go on for years. Pretending to be something you’re not almost every hour of every day is mentally draining. And the toll it takes can be long-lasting, says Vendemia. “Over time, this kind of lying actually causes you to use up the brain resources you need for thinking.”

Lying has social consequences, too, explains Victoria Talwar. She’s a psychologist in Canada. Working at McGill University, in Montreal, Quebec, Talwar studies the development of lying in children. People generally value honesty and don’t like liars, she says. So if people view you as untrustworthy, it can be bad for your relationships.

Even the kindest of prosocial lies can sometimes be risky. A recent study looked into these and found they often backfire. When you give insincere compliments, for example, you may make your friends feel good — at first, anyway. But do it often enough, and they’ll soon learn that they can’t trust your compliments. That makes those compliments meaningless. Researchers shared those findings in a February paper in Current Opinion in Psychology.

That’s why Talwar often warns parents not to give false praise to their children. “If you do,” she points out, “you undercut the value of honest praise. You lose credibility.”

Get used to it

Neil Garrett is a neuroscientist at the University of East Anglia, in Norwich, England. Emotions have an effect on how willing people are to be dishonest, he finds. He points to one study where students were given a medicine (known as a beta blocker) that dampens their emotions. These students were more likely to cheat on an exam than those who didn’t get the medicine. That may be because the medicated students felt less of the fear or anxiety that usually comes with dishonesty.

Garrett was part of a team that decided to look at the relationship between lying and activity in the amygdala. It’s a part of the brain that processes emotions.

These researchers wondered, do our emotions adapt to lying? In other words, do our brains get used to lying? To test that, the team recruited volunteers to play a game in which they could make money if they lied to a partner. The researchers scanned the players’ brains as they played to track activity in the amygdala.

At first, the amygdala was very active when someone lied to make more money. As the lies went on, however, activity in that part of the brain started to drop. And as the amygdala’s activity fell, the players lied even more.

The researchers reported these findings in Nature Neuroscience.

This brain effect may be similar to the way our sense of smell adapts to a strong odor, Garrett suspects. Enter a newly painted room and you might notice an overwhelming scent of fresh paint. But after a few minutes, you may not notice it much. Emotions might work this way, too, Garrett says. The emotion you feel when you lie might be fear or anxiety — a warning of the dangers a lie might bring. Or it might be a slight twinge that tells you it’s wrong to lie. Whatever it is, Garrett’s team showed that the more you lie, the less you feel those uncomfortable emotions.

In other words, lying gets easier the more you do it.

An honest culture

Nearly all cultures value honesty, Talwar says. And, she adds, there are things people can do to help create a culture that reinforces the value of honesty.

Finding ways to support your friends while still being truthful is one strategy. “When people’s friends are truthful with them,” she says, “it creates a culture of honesty among them.” And that, she argues, “will build stronger friendships.”

It also helps when lying has consequences. People who have never had to face consequences for their lies are more likely to lie, explains Vendemia. People tend to lie less when they know they’ll be called out for those falsehoods. However, punishing people for lying is less important than rewarding them for telling the truth, she says. This is especially important, she adds, when people share important truths about themselves. Sometimes those can be the hardest truths to tell. “Being able to tell the truth to a friend is rewarding,” she says. “It feels good.”

Most people know lying is generally bad and can have serious consequences. Science is now revealing ways in which dishonesty also can impact the brain and your ability to build the trust on which strong relationships depend.