Many U.S. football players had brain disease, data show

Severe disease showed up in 99 percent of pro players whose brains had been donated to science

Football collisions can lead to head injuries. New data from brains donated to science show that from high school players to former pros, many men sustained serious permanent damage. And how much damage occurred was not always obvious, based on symptoms reported by the men’s families.

Eugene_Onischenko/iStockphoto

American football is a very rough and tumble sport. A career of hard knocks and smashups can take a brutal toll on players’ bodies. That includes their brains, a new study shows. Most football players whose brains were donated at death for research showed severe damage, according to the largest study to date.

The finding provides more evidence linking serious brain disease with repetitive head injuries sustained during years of playing American football.

The authors caution, however, that they don’t know how representative the brains were that they studied. Players and their families had offered up these brains for study. Their choosing to do so may reflect that many of these players already had major symptoms of brain damage. So these may have been a self-selected group of the most injured of players, not a representative mix of all players. Still, the study’s authors find their new results worrisome.

They examined the brains of 202 former football players. Of them, 177 had CTE, short for chronic traumatic encephalopathy (En-sef-uh-LOP-ah-thee). The term means a brain has sustained long-term damage. CTE’s symptoms can include mood and behavioral issues as well as problems with thinking and reasoning.

Men who had played in the National Football League donated 111 of the brains studied. And 110 of these — a whopping 99 percent — had CTE. So did three of 14 high school players and 48 of 53 college players.

Twenty-seven researchers from eight universities, hospitals and research groups took part. The team based its diagnoses on brain autopsies. It also interviewed family and friends about any symptoms the players had experienced. The researchers described their disturbing findings July 25 in JAMA.

“The fact that [CTE] was so common adds to our concern about the safety of playing football,” says Gil Rabinovici. As a neurologist, he studies nerve tissues and the brain at the University of California, San Francisco. He also offered an editorial accompanying the new report. The strong link between brain damage and football injuries, he says, “hovers like a dark cloud over the game at all levels.” And that’s true “even if the study cannot address how frequent the disease is, or who is at risk.”

Growing concerns over football’s risk of CTE

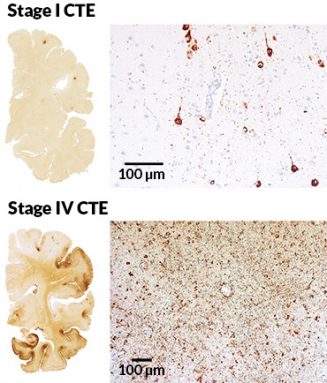

CTE can show up in athletes and others who’ve had repetitive head injuries, such as concussions. The only way to diagnose CTE is with an autopsy. In affected brains, a protein called tau goes “bad.” It inappropriately forms clumps in nerves and other brain cells. A tau buildup occurs in other brain diseases, too — such as Alzheimer’s. But where it builds up is different in CTE. Here, the protein congregates in cells around small blood vessels.

In 2008, researchers set up a brain bank to collect tissues for study. Its goal was to probe the long-term effect of head blows sustained in sports and military service. The new study focused on brains from football players provided to that tissue bank.

Neurologist Jesse Mez of Boston University School of Medicine, in Massachusetts, and his colleagues classified CTE cases as mild or severe. Their ratings were based on how widespread the tau clumps were within a brain. The severity of disease seemed to track with how long the men had spent playing football, Mez says. Among NFL players, 95 of the 110 diagnosed cases were severe. In contrast, all three high school players’ cases were mild. Among cases in college players’, just over half were judged severe.

The symptoms reported by family members were not a good gauge of how bad a man’s brain damage had been. Behavioral and mood problems — such as impulsivity, anxiety and depression —commonly showed up in both severe and mild cases of CTE. Cognitive symptoms, including memory loss, also were about the same in both groups. One big difference: dementia. It was more common in men with severe CTE than in those who had mild cases.

Why symptoms so poorly correlated with the severity of brain disease is puzzling, Mez says. “The question is: Is there something else going on?” such as inflammation.

There still isn’t a way to diagnose CTE during life. And that’s “the 800-pound gorilla in the room,” says neurologist David Brody. He works at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Mo.

Yet detecting CTE in living patients will be crucial for understanding how common it is in the NFL, “let alone in the millions of people who participated in college, high school and youth football,” says Rabinovici. For now, he says, “We need to focus on prevention of concussions and other head impacts at all levels of contact sports.”