Huge polygons on Mars hint its equator may once have been frozen

A Chinese rover used radar to reveal the hidden shapes

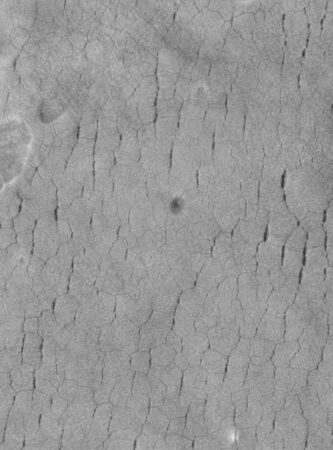

On Mars, the Chinese rover Zhurong found intriguing polygon patterns buried dozens of meters (yards) below its landing site.

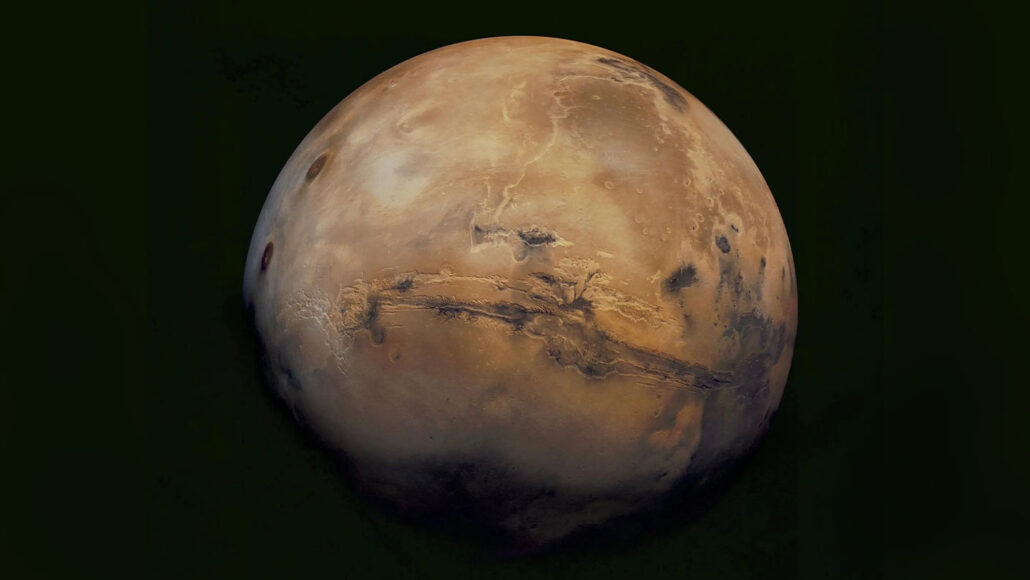

JPL-Caltech/NASA

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

By Elise Cutts

Rock that lies dozens of meters (yards) below Mars’ surface may be riddled with huge polygon patterns.

Polygons are geometric shapes with flat sides. On Earth, such patterns appear near the poles. There, sharp temperature drops can cause icy ground to cool, shrink and crack. Those cracks then fill — with ice or sand or both — to form wedges that pry the ground apart. In time, the widening cracks carve out polygon patterns.

A similar process may have created the shapes found on Mars. This would have happened some 2 billion to 3 billion years ago. If so, the Red Planet’s equator was likely once much wetter and icier — more like a polar region.

Researchers shared their finding November 23 in Nature Astronomy.

The Chinese rover Zhurong spotted these apparent patterns. It had been exploring a part of Mars called Utopia Planitia. It used radar to peer underground.

The rover spied polygons that seemed to be roughly 70 meters (230 feet) across. They’re bordered by wedges nearly 30 meters (100 feet) wide. And they’re tens of meters deep. This makes them about 10 times as large as the polygons and wedges typically found on Earth. So it’s possible the structures formed differently than our planet’s ice-wedge polygons, says Richard Soare. He’s a planetary scientist at Dawson College in Montreal, Canada. He did not take part in the Mars study.

If polygons on the Red Planet did form through a similar process as those on Earth, Utopia Planitia is not where one would expect to find them. At least, not today. Spacecraft have spotted polygons on Mars’ surface closer to the planet’s poles. But the Zhurong rover’s landing site was near the equator. This is a dry, sandy dune field.

Forming polygons near the Martian equator wouldn’t be possible today, says Ross Mitchell. To form them, the region must have been colder and wetter in the past. Mitchell is a coauthor on the new study. A geoscientist, he works at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing.

Changes in the tilt of Mars’ axis could explain such a shift in climate.

Computer models hint that in the past, the axis around which Mars spins was much more tilted than it is now. At times, it may have been so tilted that the planet basically lay halfway on its side. That would have caused what’s now the poles to receive more direct sunlight. Meanwhile, land near the equator would freeze. Indeed, Mitchell says, finding potential polygons buried near the Martian equator is “smoking-gun evidence” for that idea.

“We think of every planet other than Earth as dead,” Mitchell says. But if Mars’ axis does swing around often, he says, the Red Planet’s climate could have changed far more than we thought.