New device tells smiles from frowns — even through a mask

It analyzes someone’s cheeks for telltale clues to expressions

When you wear a mask, other people often can’t tell if you’re smiling or frowning. But a new device called C-face can. It learns our facial expressions by watching the motion of our cheeks.

damircudic/E+/Getty Images

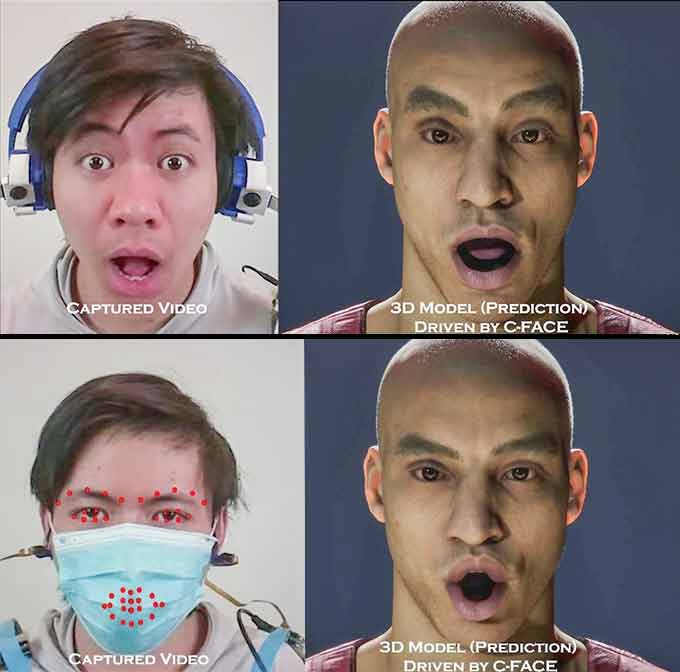

Tuochao Chen gapes. Then he sneers. Then he grimaces. As he makes faces, he wears a device that looks like a pair of headphones. But instead of playing sound, it points cameras toward his cheeks. The cameras only see the sides of his face. Surprisingly, that’s enough facial real estate to tell a sneer from a smile, or a laugh from a frown. A computer system connected to the headphones can figure out what Chen’s eyes and mouth look like without seeing them directly.

It works even if Chen wears a face mask. The system can tell if he’s smiling or frowning behind it.

Chen studies computer science in the lab of Cheng Zhang at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. Zhang came up with the idea for this system. He calls it C-face. That “C” stands for contour. It’s also a pun because the device can “see” your face.

His team’s goal is to create technology that can better understand people. Right now, our devices are mostly clueless about how we’re feeling or what we need. But over time, more devices will understand us. Zhang hopes that “everything will be smart in the future.” For example, your phone might recognize when your face looks upset and suggest calming music. For your phone to know you’re upset, however, it has to somehow capture that information from you. Such as from a camera.

But it’s not convenient to always have a camera in front of your face. What if you’re exercising, cooking or shopping? “People are more open to wearing devices on the ears or on the wrists,” notes Zhang. His team has already shown it is possible to figure out entire hand gestures from a device worn on the wrist. That made him wonder if he could pick up entire facial expressions from cameras worn on the ears.

The sides — or contours — of someone’s cheeks change as they make different faces. So a certain-shaped contour might match a specific expression. Deep learning, an artificial-intelligence technique, can detect patterns like this. It just needs lots of practice, known as training.

To train C-face, Chen and other team members made funny faces. Meanwhile, headphone cameras captured how the contours of their cheeks changed with each expression. And a camera in front of the face captured the locations of important landmarks around the eyebrows, eyes and mouth. The system learned to match changes in the contours to changes in these landmarks. Once training was complete, the device could look at cheek contours and predict the position of landmarks around the eyes and mouth that corresponded to particular facial expressions.

The researchers then fed those landmark positions into a program that created a matching virtual version of the face that looked happy, sad, puzzled, surprised or something else entirely.

Zhang’s group unveiled its new system in October 2020. The researchers shared details about it at a virtual conference of the Association for Computing Machinery Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology.

Science shaped by roomies and the pandemic

Everyone’s face is unique. So each person who uses the C-face device has to train and test it on their own expressions. To do this, Zhang’s team had to recruit volunteers. But it was spring 2020 at the time. The coronavirus pandemic had sent most of the world into lockdown. It wasn’t safe to bring anyone to a laboratory. So the team got creative.

“We got approval to conduct the study with our roommates,” says Benjamin Steeper, another Cornell student. The situation wasn’t ideal. Steeper converted one room of his apartment into “the science room,” complete with a desk, chair, cameras and everything else he needed.

Meanwhile, Chen set up his bedroom to also use for the study. Chen stars in the video that the team used for training and testing C-face. He makes dozens of different expressions, one after another, for an hour. The volunteers had to watch the video and copy each expression. They thought it was funny to have to stare at Chen making funny faces for so long. One of Chen’s roommates told him afterwards, “I will see you in my dreams tonight!”

The pandemic had another important impact on the team’s research. Face masks suddenly became part of daily life. Other software designed to recognize people’s faces — like FaceID on an iPhone — doesn’t work when someone wears a mask. “I keep seeing everyone opening their mask for iPhone unlock,” says Ilke Demir. “Looking at the contours is a very nice solution.” Demir, who wasn’t involved in the research, is a research scientist at Intel in Los Angeles, Calif.

The team showed that C-face could reveal people’s expressions even when wearing masks. This device could help you communicate more easily with friends while you wear a mask. It would do this by mapping your hidden expression onto the face of a virtual avatar. This digital version of you would match your expressions as you talk, smile or perhaps gasp.

Emoji-builder

With training, C-face also can turn someone’s real expressions into emojis. It just needs to learn what expression should match which emoji. Then, instead of scrolling through emojis to find the one you want, you just make the face at your device and it will appear on your screen, ready to post or text.

You can’t buy C-face, at least not yet. It uses too much energy and computing power right now. Demir points out that it also “needs more user studies.” The nine volunteers who took part were all researchers and their roommates. That small group does not represent the entire population. Demir points out that the researchers must make sure this device works with all hair types, skin colors, head sizes and more.

Yet Steeper is among those who looks forward to someday using C-face or something like it daily. Right now, when he’s cooking and talking to family at the same time, he puts the phone down on a table. “All they see is my ceiling,” he says. If he were wearing C-face, his family could see an engaging virtual avatar, or digital version, instead. If only they could smell the food virtually, too.

This is one in a series presenting news on invention and innovation, made possible with generous support from the Lemelson Foundation.