Measles can harm a child’s defense against other serious infections

The virus can do this by giving certain immune memory cells a case of ‘amnesia’

A measles infection can bring a rash, fever, cough and sore eyes. Other impacts of the virus, though, can last years after those initial symptoms are gone, scientists are finding.

CHBD/E+/Getty Images

The most iconic thing about measles is its rash. Red, angry splotches make this infection painfully visible. But that rash — and even the fever, cough and sore eyes — distracts from the infection’s real harm: an all-out attack on the immune system.

The immune system retains memories of the infections it fights. That helps it know what to do when it encounters familiar germs in the future. But measles wipes clean those memories. The resulting “immune amnesia” from measles can leave people at risk of developing infections from other harmful viruses and bacteria for years, scientists are finding. Pneumonia, ear infections and diarrhea are common side-effects.

That makes measles “the furthest thing from benign,” says Michael Mina. As a pathologist, he studies infectious diseases at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass. Measles increases people’s susceptibility to everything else, he says. And that has big costs.

Scientists now have a better picture of how the measles virus mounts its sneak attack. They know which cells are most at risk and how long the immune system seems to suffer. Studies helped fill in the details. They came from tests in lab animals and in human tissues and from comparing children before and after they had measles.

This new view may help explain why the measles vaccine seems to have far-reaching effects. The shot prevents deaths — and from more diseases than just measles, says Rik de Swart. He’s a virologist at Erasmus University Medical Center in the Netherlands. By shielding the immune system from one virus, the vaccine may help keep other disease-causing germs at bay.

Locking onto a target

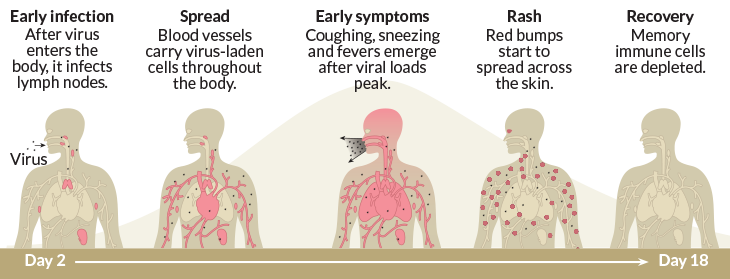

After someone with measles coughs or sneezes, their virus can linger in the air and on surfaces for up to two hours. Once inside its next victim, that virus attacks immune cells. It targets those in the nose, throat, lungs and eyes. These immune cells have a protein called CD150 on their surface. This protein allows the virus to invade, experiments on lab animals show.

Inside the cells, the virus quickly makes copies of itself. Then it spreads to places packed with other immune cells, such as the bone marrow, the spleen, tonsils and lymph nodes. The measles virus has an “enormously strong” preference for infecting immune cells, says Bert Rima. He is an infectious-disease researcher at Queen’s University Belfast in Northern Ireland.

By looking at preserved human tissue, Rima and his colleagues traced how measles invades the immune system. Eventually, newly made viral particles move to the respiratory tract. From there they can be coughed out to sicken more people. The researchers described their findings in the May/June 2018 issue of mSphere.

A severe measles infection usually lasts several weeks. It can sometimes bring ear infections and pneumonia. In rare cases, a deadly brain swelling may also occur. On their own, those are worrisome side-effects, says Anthony Fauci. He is the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Md. But the loss of immune cells also can leave people prone to infections that the immune system would normally fend off.

Memory loss

In 2013, de Swart and colleagues had a chance to study the immune effects of the measles virus in children. These kids were part of a closed-off community of Orthodox Protestants in the Netherlands. Parents in this community refuse to let their kids become vaccinated. As a result, bouts of measles have been common. The community’s last measles outbreak had ended in 2000. So it was just a matter of time before the virus took hold again.

The researchers got permission from parents to take blood samples from healthy children who never had measles. They wanted to study their immune cells. Then, the researchers waited for an outbreak. They would test the kids again after an infection.

And they didn’t have to wait long. An outbreak ripped through the community just as the researchers began collecting blood. Classrooms emptied as sick siblings packed into dark living rooms to protect their sensitive eyes. De Swart’s team had blood samples from before and after 77 of those children came down with measles.

The measles virus targets immune cells called memory B and T cells, de Swart says. These cells remember threats the body has already fought off. They also help the immune system spring into action quickly if those threats return. After the measles outbreak, the numbers of some types of the memory cells dropped in children who had caught the disease. That created an immune amnesia.

De Swart’s team reported its findings November 23, 2018 in Nature Communications.

Long road to recovery

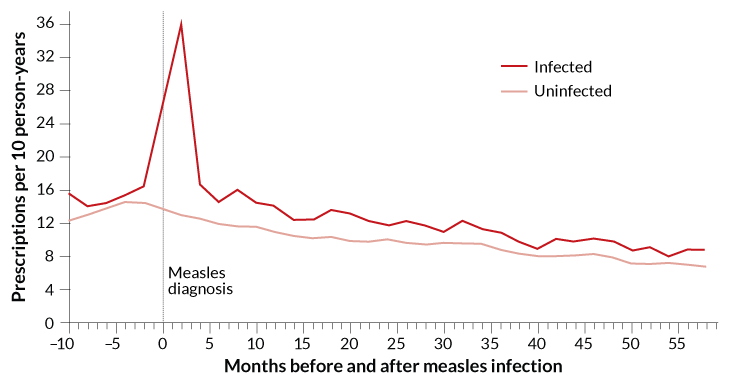

The immune system might take months, or even years, to bounce back from this memory loss. Researchers, including de Swart and Mina, compared health records of children in the United Kingdom from 1990 to 2014. For up to five years after a bout of measles, children experienced more infections than did those who never had the disease. And children who’d had measles were 15 to 24 percent more likely to receive a prescription for medicine to treat an infection. The findings were reported last November 8 in BMJ Open.

Mina and his colleagues found similar results for deaths from nonmeasles infections among children in England, Wales, the United States and Denmark. When measles was rampant, children were more likely to die from other infections, the researchers found. And this added danger from measles stuck around for a long time. Even several years out, measles survivors were more likely to die from other infections than did children who had not gotten measles.

At some point, the immune system can recover its memories. But it’s not clear how. With new methods that can measure these memories, Mina and others hope to figure that out.

Most children get over measles without a problem. “The immune system is incredibly resilient,” de Swart says. Still, measles is not an innocent childhood disease. For some people, the outcome can be severe.

But there’s a vaccine for measles. With it, “we know how to prevent this potentially lethal disease,” Mina says. “It’s so simple.”