Mercury unveiled

A new mission to Mercury is revealing surprising, never-before-seen details about the innermost planet.

By Emily Sohn

Astronomy isn’t a popularity contest, but some planets seem to get all the attention. Jupiter is biggest. Saturn has lots of rings. Mars may harbor life.

For years, Mercury has lurked in the shadows of its flashier neighbors. Now, the smallest planet finally is getting its time in the spotlight.

Last month, scientists enjoyed their first good look at Mercury in more than 30 years. On January 14, NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft flew by the planet. Along the way, it collected a variety of data, including more than 1,200 high-quality images.

What’s more, the flyby revealed a large section of Mercury that had never been seen before at close range. In recent years, spacecraft have visited most of the solar system. But Mercury, the planet closest to the sun, remained largely unexplored.

|

|

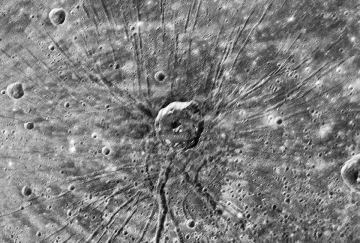

MESSENGER took this image on January 14 of regions on Mercury that had never before been seen from a spacecraft.

|

| NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington |

“There aren’t very many new worlds to be found,” says Clark Chapman. “Mercury really is that.” He’s a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., and a member of the MESSENGER science team.

As analyses get under way, surprises are already piling up. Observations include tons of craters, huge cliffs, evidence of volcanoes, and a strange, spider-shaped formation.

And that’s only the beginning.

MESSENGER will fly by Mercury again in October and a third time in September 2009. In 2011, the spacecraft will enter a yearlong orbit of the planet. It will be the first spacecraft ever to orbit Mercury.

As the mission progresses, scientists hope it will answer a long list of questions about the planet’s surface, its atmosphere, and other details.

“I would guess the data we got in this first flyby are equivalent to all the previous knowledge we’ve had of Mercury from all sources,” Chapman says.

“When this mission is done, we will really figure out how Mercury works,” he adds. “And as we think about why it is different from Earth, it will give us some insight into our planet and into how planets formed.”

Mission findings

Much of what we know about Mercury comes from NASA’s Mariner 10 mission, which flew by the planet three times in 1974 and 1975. Although its glimpses of Mercury were brief, Mariner 10 helped confirm some basic discoveries about the planet—such as that it has a very thin atmosphere, a magnetic field, and a large iron core.

In photos taken by Mariner 10, Mercury resembled the moon, which has lots of craters and a mostly unchanging surface. The two objects are also nearly the same size.

But Mariner 10’s instruments were less advanced than MESSENGER’s are. And the earlier Mariner mission saw just one side of Mercury in daylight—leaving about 55 percent of the planet unseen.

During its recent flyby, MESSENGER was able to observe about half of the remaining area. (The spacecraft will see the rest of the planet in October.) The new images show that Mercury is different from the other rocky objects in our inner solar system—Venus, Earth, Mars, and the moon.

“It was not the planet we expected,” says Sean Solomon, a planetary scientist at the Carnegie Institution of Washington (D.C.) and principal investigator of the MESSENGER team. “It was not [like] the moon. It’s a very dynamic planet with an awful lot going on.”

One of MESSENGER’s most interesting discoveries so far is a strange formation called the Spider. Unlike a real spider, which has only eight legs, this one has more than 50 leglike trenches that stretch out in all directions from a large, relatively dark central area that surrounds a crater that is 40 kilometers (25 miles) wide. The entire structure lies within another huge crater called the Caloris basin.

|

|

Mercury’s Spider is unlike anything seen elsewhere in the solar system.

|

| NASA/JHU APL/Carnegie Institution |

“The Spider feature is unlike anything we’ve seen anywhere in the solar system,” Solomon says. There may, however, be similar features on Venus, Chapman notes.

How did the Spider form? “We have theories,” says Louise Prockter, a MESSENGER team member from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md. “But the real answer? It’s anyone’s guess,” she says.

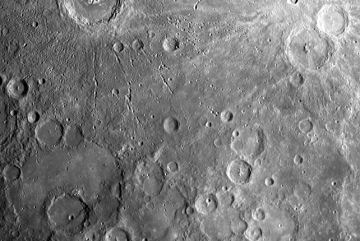

Besides the Spider, MESSENGER’s first pass of Mercury revealed a surprisingly large number of craters. These bowl-shaped depressions form when objects from outer space strike a planet or moon, or when material ejected by these impacts strikes outside the initial crater. Craters can also develop when volcanoes erupt.

|

|

On January 14, the MESSENGER spacecraft’s narrow angle camera revealed hundreds and hundreds of craters on Mercury’s surface. The crater in the lower left corner of this image measures about 230 km (143 miles) across. The crater nestled inside it is about 85 km (53 miles) across.

|

| NASA/JHU APL/Carnegie Institution |

In just one section of one of MESSENGER’s images, Chapman counted more than 700 small craters. Each measured between a quarter-mile and several miles across. By counting craters, measuring them, and analyzing their locations, he hopes to figure out when these features formed.

Studying craters can also show if and when molten material emerged from deep within the planet’s interior. MESSENGER has already revealed that there is a surprising amount of this volcanic activity. Further observations will reveal more about what’s happening inside the planet.

At long last

Scientists have had to wait a long time to get a good look at Mercury, mostly because the planet is tough to reach. Heat is one reason: Temperatures on the planet can hit 800 degrees Fahrenheit (roughly 425 degrees Celsius). It’s taken decades of engineering research to develop solar panels, cameras, and other equipment that can perform under such extreme conditions.

Getting into orbit around Mercury also requires some feats of physics. The sun’s gravity accelerates any spacecraft that ventures near the star. MESSENGER will therefore have to fight the sun’s gravity in order to slow enough for Mercury’s gravitational field to capture and hold the spacecraft in the planet’s orbit.

Braking the spacecraft’s speed by firing up its rockets would use lots of fuel (which would have been too heavy for MESSENGER to carry). So instead, the spacecraft will rely on the tugs of gravity from Earth, Venus, Mercury, and the sun to weave around the planets until it reaches the correct position and speed.

The strategy is clever, but it takes a while. In 2011—nearly 7 years after it left Earth—MESSENGER will finally enter Mercury’s orbit.

|

|

MESSENGER took off from Launch Pad 17-B, at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida, on August 3, 2004 at 2:15:56 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time.

|

| NASA |

The wait should be worth it, according to the MESSENGER researchers. Spacecraft that orbit planets provide a lot more information than do spacecraft that simply fly by planets. And as the mission continues, scientists hope to solve some of Mercury’s mysteries.

Why, for example, is Mercury the only planet in the inner solar system—other than Earth—that has a magnetic field? And is it true, as some planetary scientists theorize, that Mercury formed in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter before moving to its present location?

Mercury’s climate has also raised a number of questions. The planet is an extremely hot place, but it has wild temperature swings, with an 1100ºF (about 600ºC) difference between day and night in some places. Its poles always remain a frigid –300ºF (about –180ºC).

In the shadows of craters in the polar regions, scientists have even observed what appears to be water ice. “If Mercury can have ice,” Chapman asks, “Why doesn’t the moon? And where does the water come from?”

The questions go on and on. After decades of planning, watching, and nervous waiting, MESSENGER scientists are excited to see what the mission reveals next.

“I want to emphasize that the best is yet to come,” says Robert Strom, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona, Tucson, and member of the MESSENGER research team.

“What we’re seeing here is just the tip of the iceberg,” he adds. “Wait until we go into orbit and make two more flybys . . . This is a whole new planet we’re looking at.”

Going Deeper: