Meteorites likely wiped out Earth’s earliest life

The biggest smashups would have boiled off oceans and obliterated life

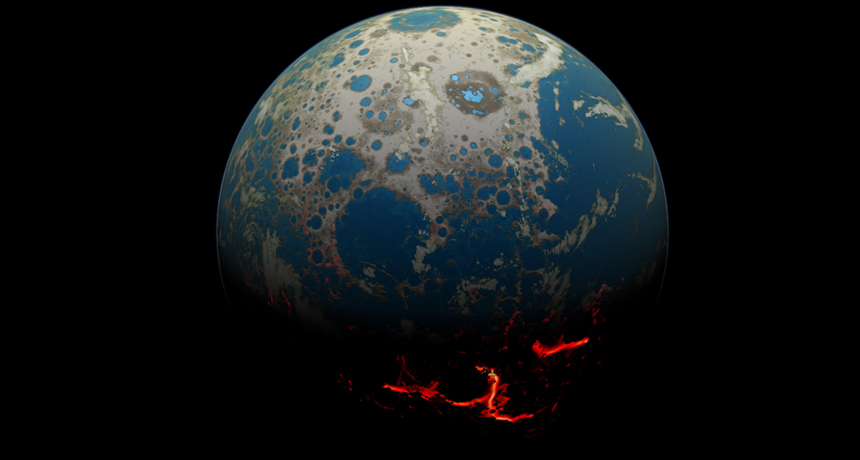

Mega-meteorites pelted early Earth. They would likely have created magma-gushing gashes (red lines in this artists’ rendition) and killed off any emerging life — until 4.3 billion years ago.

S. Marchi

Repeatedly during its early history, Earth was bombarded by space rocks larger in diameter than the state of Utah. Such collisions likely killed off any emerging life on the planet’s surface — probably again and again. The last of these death rocks struck around 4.3 billion years ago. At least that’s the estimate that scientists propose in the July 31 Nature. This date offers an upper limit to how long our planet may have continuously sustained life.

Earth appears to be around 4.6 billion years old. For its first 800,000 years, the planet was a hellish place. That’s why geologists call this the Hadean eon — after Hades, the Greek god of the underworld. Debris left over from the solar system’s creation regularly slammed into Earth. This would have boiled away the early ocean and coated the planet with molten rock.

But scientists think that it was during this chaotic time that life began.

“If life on Earth emerged before [a] final sterilizing impact, it may have been completely erased,” says Simone Marchi. That’s right: Rendered extinct. “Life would have had to start all over again,” concludes this planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo. She led the new study.

So much material struck Earth during the Hadean that it would have built up the planet’s surface by a height equal to that of Mount Everest. These impacts shaped the emergence of tectonic plates. Those relatively thin, migrating slabs of rock make up Earth’s surface, floating over a layer of molten rock below. Over time, those slabs continually rise out of the molten rock and submerge again. Their activity, which renews Earth’s surface, plays out over billions of years.

It also means that few surface rocks remain that are older than around 3.8 billion years old. So our planet holds no obvious record of events earlier than that.

In search of records for even earlier collisions, Marchi and her colleagues looked to the moon. Why? Its surface lacks the recycling action of plate tectonics, so the moon still shows scars from early asteroid impacts.

|

This animation shows the bombardment of early Earth by meteorites (depicted as circles). Although they eventually hit virtually every part of the planet, their sizes tend to decline with time (older hits in red, progressing to the more recent hits in dark blue). S. Marchi |

Scientists can determine the ages of those very ancient impacts by crater counting. As a crater ages, newer meteorites pock its surface at each new impact site. During Apollo missions to the moon, astronauts retrieved moon rocks. Back on Earth, geologists dated rocks collected from lunar craters. Scientists can estimate the age of the moon’s large and old craters by counting the number of smaller, fresher ones within the older ones.

Marchi’s team used this information to estimate the number, frequency and size of asteroids that likely impacted early Earth. Of course this works only if they assume both had a similar impact history.

The team then created a computer program to simulate Earth’s early asteroid bombardment. And the moon data suggest that asteroid impacts became smaller and less frequent with time. The computer also suggested that every bit of Earth’s surface had at some point been covered in a magma-oozing crater created by an impact.

Three to seven asteroids larger than 500 kilometers (roughly 310 miles) across probably struck Earth during this early time. At least, that’s what the computer program indicates. Any of these could have vaporized all of the planet’s surface water. This hot, sizzling rock and lava would likely have destroyed any life then living on the surface.

The last of these life-sterilizing impacts took place 4.27 billion years ago, the researchers estimate. Fossils preserve evidence of life on Earth going back only 3.8 billion years (although some scientists dispute that earliest evidence).

Geochemist Jeffrey Bada works at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, Calif. He believes that a better understanding of early asteroid bombardment will help researchers probing the origins of life. Earth’s really big asteroid smashups would have obliterated any cells that had evolved, he says. “Life could not have started prior to that and survived.”

Power Words

asteroid A rocky object in orbit around the sun. Most orbit in a region that falls between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Astronomers refer to this region as the asteroid belt.

crater A large, bowl-shaped cavity in the ground or on the surface of a planet or the moon. They are typically caused by an explosion or the impact of a meteorite or other celestial body.

Hadean eon A period early in Earth’s history that extended from 4.6 billion to 3.8 billion years ago. During this time, the solar system was still organizing into discrete objects, and the rocky planets (like Earth) were cooling into solidified structures. No known rocks exist from this period. Any that were around back then probably eroded, or they likely melted as they were drawn deep below Earth’s surface through the movements associated with plate tectonics.

lava Molten rock that comes up from the mantle, through Earth’s crust, and out of a volcano.

magma The molten rock that resides under Earth’s crust. When it erupts from a volcano, this material is referred to as lava.

meteor A lump of rock or metal from space that hits the atmosphere of Earth. In space it is known as a meteoroid. When you see it in the sky it is a meteor. And when it hits the ground it is called a meteorite.

molten A word describing something that is melted, such as the liquid rock that makes up lava.

plate tectonics The study of massive moving pieces that make up Earth’s outer layer, which is called the lithosphere, and the processes that cause those rock masses to rise from inside Earth, travel along its surface, and sink back down.

sterile An adjective that means devoid of life — or at least of germs. (in biology) An organism that is physically unable to reproduce.

tectonic plates The gigantic slabs — some spanning thousands of miles — that make up Earth’s outer layer.