Mimosa plant ‘muscles’ fold tickled leaves fast

Specialized cells can close and then re-open mimosa leaflets — over and over

A Mimosa pudica plant leaf shuts like a book when touched. Later it will re-open. Scientists have learned how specialized cells in this plant make that muscle-like action possible.

Debu Durlav/iStock/Getty Images Plus

By Susan Milius

Close. Open. Repeat. When jostled, a mimosa plant’s feathery leaflets fold up. Later, they relax and unfold. If the leaf is touched a second time, the leaflets fold again. Scientists have now discovered details of how the mimosa manages this muscle-like movement.

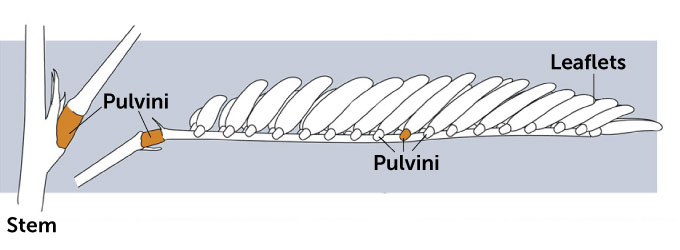

Mimosa leaflets fold thanks to tiny bulges of specialized cells, called pulvini (Puhl-VEE-nee). Special quirks of these bulges speed the folding, says David Sleboda. He’s a biomechanics researcher at the University of California, Irvine. “I think that these particular organs are really cool because their motion is reversible,” he says, which makes it look more like animal motion.

Scientists had already worked out the basic chemistry that drives this folding. Sleboda is part of a team that has now looked at microscopic details in pulvini that make this shape change possible. The team reported its findings February 6 in Current Biology.

Design that delivers

When a deer or something else nudges a mimosa leaf, ions shift from one side of a pulvinus bulge to the other. Water follows the flow of ions. The cells that lose water deflate and sag. Those on the other side swell up. When this occurs in multiple pulvini at the same time, the leaf moves. The halves of these feathery leaflets fold toward each other, as if an invisible hand gently closed them like a book.

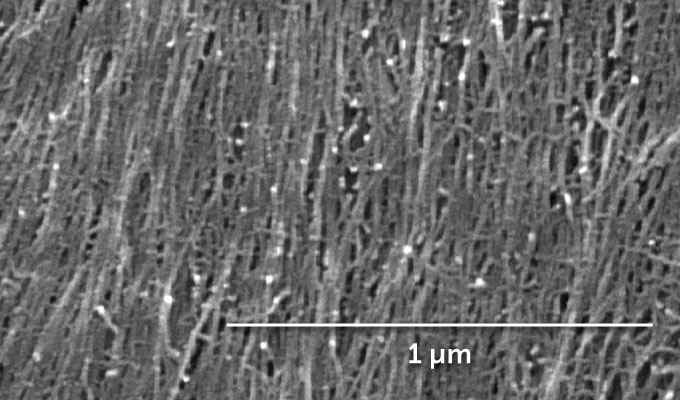

Sleboda and his colleagues also looked at long fibers in some cell walls. Mats of these fibers may help plant-muscle cells swell more efficiently. The fibers could work like straps, keeping the cells from ballooning out in all directions. The straps seem to guide the swelling. This helps leaflets fold upward.

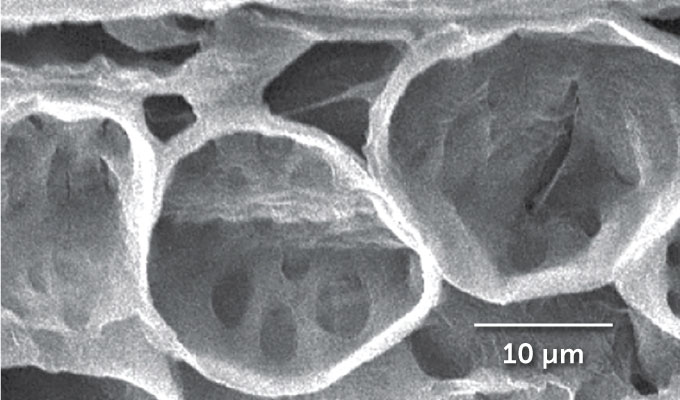

Tricks found in their cell walls could help them bulge fast. Those cells have wrinkled tissue that expands as water floods in. They can also have zones called pit fields with lots of tiny, porous caverns. It’s likely that water could easily rush through these thin-walled pits in response to a bump from a grazing deer.

Even the arrangement of the pulvini looks useful for expanding and shrinking. A cross-section of the tissue reveals a pattern “like the bellows of a concertina,” says Sleboda.

Family of folders

This type of mimosa is native to the Caribbean and South America. It’s now found across the southern U.S., too. Many people call it the “sensitive plant.” There are other plants in the same family — legumes — that move their leaves as well, says Thainara Policarpo Mendes. She’s a botanist at São Paulo State University in Botucatu, Brazil.

Some of the plant’s relatives also close their leaves fast. Many are slower. What Mendes wonders about is why the leaves close at all.

Scientists have come up with some possible explanations. A stick-shaped leaf might be less appetizing to an animal. Also, folding leaves might help a plant lose less heat on cold nights.

Sleboda has heard lots of hypotheses but remains skeptical. “There’s not a ton of research,” he points out. That suits him just fine. “My favorite thing about sensitive plants’ leaf closing,” he says, “is that we don’t know why they do it.”