Dogs and other animals could aid the spread of monkeypox

The virus may be able to infect species such as foxes and rats, aiding its global spread

A dog in France caught monkeypox from its owner. This raises the possibility that other animals could become infected, too. The dog is the same breed as this Italian greyhound, which was photographed in Montréal, Canada.

Anne Bentz/EyeEm/Getty Images

In August, researchers reported that two men in France had spread monkeypox to their dog. This was an important development in the recent global outbreak of the disease. It was the first time someone was known to pass monkeypox to a dog. And it hinted that other animals could catch the sometimes deadly virus.

Some scientists worry that monkeypox could establish animal reservoirs outside of Africa for the first time. Animal reservoirs are groups of animals that serve as long-term hosts for a virus.

People who get monkeypox tend to develop a rash. They may also have a fever, chills, aches or other cold-like symptoms. In fewer than 10 percent of cases, the disease can be deadly.

Monkeypox often spreads through skin-to-skin contact or contact with body fluids. But even more casual contact — such as dancing near infected persons — may spread the virus. So can touching something that an infected person has used. This includes bedding and clothing. (The men in France whose dog caught monkeypox let the dog sleep in their bed.) The virus lingers more often on soft, porous materials (such as fabric) than on hard surfaces.

Outbreaks of monkeypox have occurred in countries in Central Africa for decades. But over the last few months, the illness has been spreading elsewhere. More than 54,000 cases have emerged across the world. There have been more than 20,000 cases in the United States already.

Understanding how monkeypox spreads in animals could help forecast how bad the global outbreak will get. It could also offer clues about how to protect people from the virus.

Spreading between species

Monkeypox usually spreads from animals to people. In some parts of Africa, rodents are often to blame. Such animal-to-human viral jumps are called “spillover” or “zoonotic” (Zoh-uh-NOT-ik) infections.

Grant McFadden studies pox viruses at Arizona State University in Tempe. A case that moves from humans to a dog “is a classic case of reverse zoonoses,” he says. That is, a case of a viral disease hopping from people back into other animals. This is also known as “spillback.”

Spillback is fairly common with other viruses. People are known to have given COVID-19 to dogs, cats and zoo animals, for instance. Some pox viruses, including cowpox, can infect a wide range of species. Meanwhile, others like smallpox can infect only one or a few species.

Scientists don’t know how widely monkeypox can spread among animals other than rodents. The virus is known to have infected 51 species. That includes apes and monkeys. Other animals, such as anteaters and opossums, also have been infected.

Right now, monkeypox circulates regularly among animals only in some parts of Africa. Since 2017, some people in Nigeria have also caught monkeypox from animals or from each other. But the new global outbreak could create more chances for the virus to jump from people to animals. If that happens, the virus could form reservoirs — establish itself in animal populations — around the world. Those reservoirs could lead to repeated infections in humans and other animals.

New research suggests that monkeypox may be able to infect two to four times more species than once thought. This estimate was based on the findings of a machine-learning system. That system weighed several factors that could contribute to a species becoming a new host for monkeypox. Among these were the genes in the virus and the diet and habitats of potential hosts.

The system predicted that about eight in every 10 potential new monkeypox hosts are rodents or primates. But pets like dogs and cats could also be susceptible.

The researchers who built this machine-learning tool didn’t know about the dog in France when their system made its predictions. So, the case of the infected dog “was a quite nice validation that the method works,” says Marcus Blagrove. He studies viruses at the University of Liverpool in England.

Animals of concern

There are two potential monkeypox hosts that researchers are especially worried about. One is the red fox. The other is the brown rat.

Foxes scavenge for food in garbage. That could bring them into contact with germs on trash from people with monkeypox. Brown rats, meanwhile, are common in sewers. There, they could pick up an infection from feces containing monkeypox.

Red foxes roam much of the Northern Hemisphere. And brown rats are found on every continent except Antarctica. As a result, they could become key spreaders of monkeypox at many sites.

Blagrove and his colleagues also identified three European rodents that could become reservoirs of the virus. One is the herb field mouse (Apodemus uralensis). Another is the yellow-necked field mouse (Apodemus flavicollis). And last is the Alpine marmot (Marmota marmota). Big populations of all three species reside in various sites that could be ideal for passing the virus around.

“These are examples of wild animals that might be a reservoir. We can’t say for certain,” Blagrove says, “but they might be susceptible.” Keeping an eye on those species — along with foxes and brown rats — could help curb monkeypox’s spread.

Wider spread

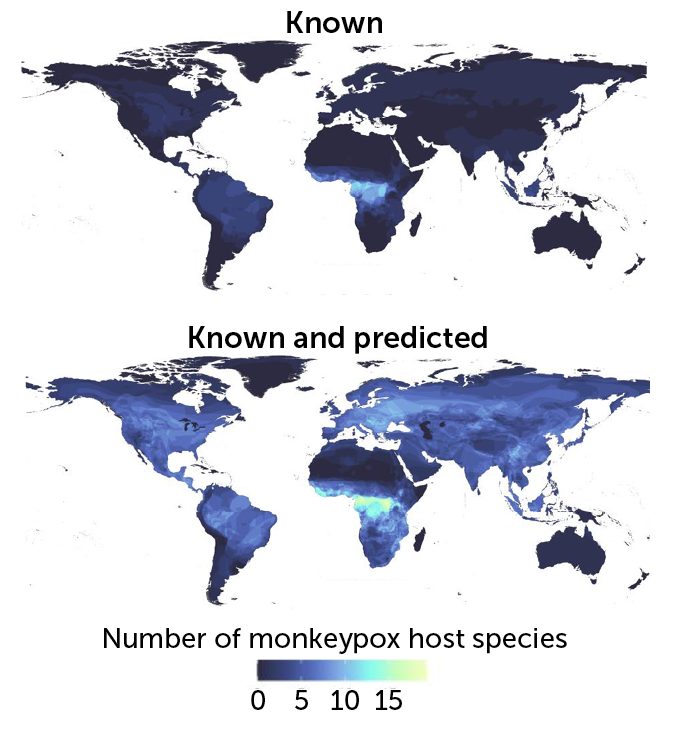

Monkeypox is known to infect 51 species, including humans. Most known hosts are African animals (light blue, top map). A new study predicts the virus could infect a broader range of species around the world (bottom map).

Mapping monkeypox’s known and potential host species

Accidental vs. established infection

Just because an animal can get infected with monkeypox doesn’t mean it can pass the virus on. “There is a difference between accidental hosts and a reservoir,” says Giliane de Souza Trindade. She studies pox viruses at the Federal University of Minas Gerais in Brazil.

Accidental hosts can get infected, but don’t spread the virus to others very much. A true reservoir species must be able to easily pass the virus from animal to animal. Once a virus is in a reservoir species it may sometimes pass to people.

If dogs can easily get monkeypox, they may be able to pass it to humans, other dogs or other animals, Trindade says. The virus could spread through dog feces or saliva. She says pets of people who get monkeypox should be isolated from sick people and from other animals outside the home.

Trindade and her colleagues are preparing to study pets of people with monkeypox. They hope to learn whether the virus passes easily to cats and dogs.

She is even more worried about live animal markets. Here, she notes, “animals are in cages very close together.” People frequently pass by these sites. Such settings are ripe for transmitting viruses between species. The COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, probably got its start at a live animal market in Wuhan, China.

McFadden stresses that the dog’s case is still one isolated report. “Is this a rare thing, or have we just not paid attention to it?” he asks. “We don’t know.” For now, he says, efforts should focus on containing the outbreak. People who are infected should take care not to pass the virus to their pets. But this one case shouldn’t cause undue worry, he adds. “We’re not at the panic button stage just yet.”

Scientists are also still learning how monkeypox spreads between people. Some may have monkeypox, but not develop symptoms. It’s unclear whether these people can spread the virus to others. If they can, then just vaccinating people around those with symptoms may not be enough to contain an outbreak.